Lanfranco Aceti

Visiting Professor and Research Affiliate

Art, Culture and Technology @ MIT

Email: aceti@mit.edu

Web: http://www.lanfrancoaceti.com

Google Scholar: citations?user=snEM2x0AAAAJ&hl=en

ORCID: 0000-0002-6835-2382

Twitter: lanfrancoaceti

Reference this essay: Aceti, Lanfranco. “Remainders at the End of a Summer Bliss: Or How We Capitalized on the Spectacle of Our Death at the Beach.” In End of a Summer Bliss. Cambridge, MA: LEA / MIT Press, 2017.

Published Online: August 15, 2017

Published in Print: To Be Announced

ISSN: 1071-4391

ISBN: 978-1-906897-88-8

Repository: https://contemporaryarts.mit.edu/pub/remainders

Abstract

At the end of the summer only remnants endure and a profound sweet melancholy sweeps the soul in anticipation of the winter. It is a moment of reflection on what has happened and what has gone amiss, on what is left and what is to come, on what perhaps will never happen, and what will repeat itself over and over again. In the last of the summer days with the last rays of the sunset light, the sandy beaches let the shadows cast their dark warnings of what are times to come. This is a feeling that is often experienced by people on the beaches of Athens and Rome who have an understanding of their history and a developed philosophical sensibility towards the complexities of life itself.

End of a Summer Bliss is an exhibition in which the works of art, the curatorial framework, and its timing, all together conjured a vision of the world outside of traditional schema. A few months later, I remain convinced more than ever that this was not just a show, but a watershed moment in which Bill Balaskas’s works of art were able to convey—from the locus of the burning city of Athens—what the current world is all about. These are times in which I have been re-considering my own Mediterranean heritage in contrast to the globalized ideologies arriving from the West and the North of Europe.

Rome is, once again, “learning from Athens,” which is understood within the context of that Horacian framework of Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit and perhaps, once again, the works of art of Athens will bring their knowledge to agresti Latio.

The exhibition was about the connections between Athens and Rome, but more importantly it was about the oppressed and forgotten people of the world—who nevertheless are still able to express their voices, thoughts, and desires independent of the various frameworks of exploitation.

In the burning cities of Athens and Rome there are those who, perhaps, are able and willing to commit to an action.

Keywords: Summer, end, dystopia, utopia, post-democracy, post-citizenship, melancholia, Mediterranean

“Then the cicadas again like kindling that won’t take.

The struck match of some utopia we no longer remember

the terms of—

the rules.

What was it was going to be abolished, what restored?”

The Errancy, Jorie Graham. [1]

“L’estate sta finendo

e un anno se ne va

sto diventando grande lo sai che non mi va.

In spiaggia di ombrelloni

non ce ne sono più…”

L’ Estate Sta Finendo, Nelson, 2014. [2]

An Introduction to Aesthetic Bliss, Serendipity, and Madness

Somehow there is the expectation that a rationale will pervade a curatorial statement and introduction to an artistic body of work. Particularly in the Anglo-Saxon empirical techno-scientific understanding of the world, which is currently based on the sanctity of data, there is the expectation of words to measure a common sense of everything.

This is a curatorial essay that is a statement, an analysis, and a diary of a Barbarian’s aesthetic return to his Mediterranean roots; a return of a foreigner to his homeland, traversing and re-discovering the past, dreading the future, within a no longer recognizable present. It is as if Medea (played by Maria Callas, and in the complexity of Pasolini’s interpretation of mythological reality) was here re-incarnated, writing no longer about reality, but the perception of an inner reality, distinct from the hyper-mediated perception of what reality should be and how it should be consumed by the masses.

It is not by chance that I choose Medea and her counterpart Jason as representatives of two different worlds—the barbarian and the civilized, the utopian and the dystopian—to clearly represent that there can be at times two coexisting and diametrically opposing perceptions of reality. Both of those perceptions are at the same time true, and can only exist as warring factions in order to function and define each other’s meaning and modus vivendi; or, in this case, each other’s modus moriendi.

Balaskas’s works of art traverse this landscape with poetry, whimsicality, and a carefully staged flightiness. By presenting the quotidian and our superficial approach to it, his work short-circuits the modalities of consumption and interpretation of contemporary society, its crises, and its dualistic political ideologies—all of which have failed and are failing. The works of art, the exhibition space, and the curatorial staging all conspire to present the viewer with the final moments of the end of a pleasurable time when, with the realization of a ruinous terminus, the dread seeps in that those are indeed the last moments of bliss before one will soon have to go back to the daily grind. It is in that moment that a Mediterranean melancholia touches the body, and as the sun goes down, one soaks in the very last of its rays with the sound of the waves crashing and of innumerable cicadas singing. All in the hope that it may not be as bad as once dreaded, and in the illusion that this bliss may still be available next year. These are the last moments of the last of the summer days, when the knowledge that all is lost clings to the illusion that there is still time to be had next year, and Atropos will not cut the thread… Not yet.

Somehow, we have all been there: between the bliss and the foreboding certainty of the end, with the clear notion of winter speedily and inexorably approaching. With an unwillingness to raise and fight it, one has only the desire to bathe in the last moments of a glorious landscape at sunset; diverting the eyes from a beach covered in discarded objects, trash, and solitary people, stubbornly extending that moment to its furthest possible end.

Via a series of new works under the name, Remains of a Summer Bliss, Balaskas orchestrates a psychological drama which requires a special sensibility from the viewer. Composed of small things and messages, the exhibition asks the viewers to observe the works of art with that same undefinable feeling with which one looks at the trash left on the beach as the summer days culminate and dissolve, casting upon them the questions that trouble our collective minds. Melancholia, disappointment, dread, and the hope for another summer seamlessly intermingle breeding parallels and allegories. The trash is no longer just that, but rather an allegory of human existence and human beings—commodified, used, abused, and left there to their own final destiny. Humanity and garbage amalgamate in a perspective in which human beings are not solely the refuse of an economic and political process in crisis but also the producers of the accumulating waste. Humanity—wasted and wasting—stands in a corner of the universe, in its own limited time span and with its own limited visions, as a measure of a petering out failure upon which the last of the summer light descends, obedient to physical laws and oblivious to the temporary drama oozing from the ruins of human existence.

Athens Is the Measure of All Things

It is with a certain pride—pride in the grandiose failure of a decadence that can run into maddening hyperboles and gestures—that I look at Athens, once again, as the measure of all things. It is in this aesthetic that Athens lets us rediscover a grandeur, even if it is that of looking at the end or raising the glass to the constant production of ruins, which the Mediterraneans seem so able to continuously produce.

“Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.” [6]

Balaskas’s works of art are this measure, a new silent emotive analysis, which moves beyond the squabbles of categories imposed from the outside: orientalism, north and south, victimization, exploitation, pandering, servilism, acquiescence, and a corrupting sense of survival at all costs.

It is, in many ways, tiring to observe and read the various contrivances in which the Mediterranean employs to sell itself: now, in the current crisis, as the victim within an aesthetic of all-encompassing victimization; then, from the Northern perspective of the South, as a land to exploit; and, finally, as the Orient—suddenly and hypocritically borrowing from the East notions that were rejected since Greece was supposed to be part of the West. Thus, we observe the churning out of essays, curatorial statements, and artists’ work which, in a new wave of ‘fake’ nationalism, continue to play to the tune set by the ever-arriving new conquerors.

These are harsh words, but they are the same words that I could have used for my own compatriots. They—themselves the joint inheritors of the Greek-Roman cultural paradigm—now cowardly stand and look at the burning pyres of Athens, watching from the same terrace where Emperor Nero stood gazing at the fire which devoured Rome. They stand and hope, my compatriots, as their ancestors stood and hoped that their homes would not be destroyed, or hoped that even if their homes were to be destroyed they would be able to ask favors of the Emperor and build them again. I can see them, those compatriots, tearing up at the ‘sacrifice’ of their family members charring in the fires whose immolation would allow them to continue living, and when asked by the Emperor why they were crying I can see them promptly quip: “It is for the delight of your music, Oh Emperor.”

In this world of too familiar Mediterranean cowardice for the sake of survival, Balaskas’s works of art have ‘balls’; as do the works of another Greek artist, belonging to the generation preceding Balaskas: Nikos Navridis. Navridis has been able to turn his back on the ‘world’ and explore the landscape from personal experience, specifically from a personal reinterpretation of a collective tragedy that, like Pasolini’s Medea with her tragic screams and invocations to deaf deities, does not recognize the land any longer. Both Balaskas and Navridis are artists that bring emotions into their work and not just a pandering to the aesthetic of the victors or the victims. These are artists who are not servile beings ready to see their family burnt in order to receive favors from the ever-changing Emperors of the time.

There is a risk, as there is always in the precarity of Mediterranean life, in doing things that are counter-current. But these are the last days of a summer bliss, and it is in this bliss of the end of the world, a world within which I feel I no longer have a stake, that I can say what I want. It is at the end of this world that artists like Balaskas and Navridis can indeed say what they want.

Somehow I am convinced that someone was standing with Emperor Nero on that terrace while he was singing, for no other reason than that a self-absorbed idiot will always want an audience. As I am also convinced that a knife must have been there, laying about between plates of fruits, pork, beef, and other wild game. And even if there was no such instrument, like Ecuba, with her own fingers, he or she—slave or free folk—could have plucked the eyes out of that monster, uniting his screams with the screams of burning bodies raising from the then Caput Mundi.

There is no other reason for me to be curating this show and writing this text, but the conviction that Balaskas’s works are actually elegantly, nicely, gently, and politely tearing those eyes out. There is something to his works that obliges me to revisit them, over and over again, and that is the measure of the distance between my own barbaric being and his ability to sweetly seduce the viewer in the most perverse slow acknowledgement of the ‘unpresentable remainder.’

It is in very few works of art, and in Balaskas’s works of art in particular, that the independence of thought and the power of measure can be rediscovered, not according to convenient and appropriate messages pandering to the moment, but by firmly standing within the harmony and disharmony of things and events. Both as mirrors of each other, and mirrors of ourselves, in a slow process of seduction that involves the audience in something of which they do not necessarily grasp the breadth, or the implications at first. The process of preparation and organization for a space in which the artworks may actually happen is a reflection of that Mediterranean disguise—veiling and unveiling, saying and not saying—which can only be experienced via the measured harmony of all its parts.

Athens is still the measure of all things for no other reason than that there are artists still able to speak to the world of dark and light—artists who are not just selling trinkets in an upscale bazaar for the 1% of tourists looking for a high-end, decadent, and safe orientalist thrill.

Graecia Capta Ferum Victorem Cepit

“Greece, when captured, captured her Barbarian conqueror,” is my translation of the phrase that shaped my early understanding of the power of art. It is a phrase that continues to shape my understanding of what art is and what it certainly is not: the servile pandering to this or that fashion, this or that master.

It is for this reason that Remains of a Summer Bliss may be presented as the narrative surrounding the beginning of the end of days, but even this seemingly positive remark is not the full representation of the aesthetic narrative fabricated by Balaskas. This is the end of a summer time, the end of a time of plenty, the end of a time of love, the end of a time of accord (or at least of its representation as being such). Medea decided at some point that the summer days had gone, that her relationship with Jason had reached an end, and that the end should not be on Jason’s terms, but on her own terms.

These were the terms of the barbarian who had nothing left to loose, nothing to apologize for, nothing to perceive but her own despair. Starkly standing against her past was a future filled with poverty, indignity, and terror… The remains of a love whose collapse had drained her and had made her old. She was left with an antique, barbarian world that she had rejected and a civilized world that had shattered a utopian life that never came to be. Medea was left with the reality of loss, in no uncertain terms of fear and solitude, which could only be embraced by fully bringing life to its ultimate apotheosis: death.

Balaskas’s exhibition brings all of the above to the fore, both as celebration and tragedy. This takes place through a staging in which tragedy is not placed in the events themselves, but in the role that we all play in a post-postmodern tragicomic scenario, which ultimately leads to our own death. His works hint at the complexity of this role and attract the viewer’s eyes with an almost farcical analysis of who we are—as Mediterraneans, as foreigners, as barbarians sitting at the bar drinking coffee and talking about soccer, as champagne socialists on the beaches of Capalbio, as miserable old imperialists, and joyful new colonialists wrapped in cash. Remains of a Summer Bliss offers the ultimate failure to its viewers: their incapacity to catch all of the emotional charge of the artworks, all of the complexity of its references, trapped in a superficiality of our own making.

All ties to the land and the past are severed, and the viewer, like the artist, is asked to contemplate, with Medea’s gaze, the horizon of a non-existent future at the end of the last of the summer days.

It is for this reason that I feel no shame in defining Balaskas’s artwork ballsy. There is a standing up against conformity that is not mannerism—there is quite enough of that in the crowds of dignitaries, critics, artists, and curators jetting around the world in a constant bleating from one biennial to the next. Instead, there is what could only be defined as a Spartan strength in works that present themselves as what they are, and demand of us to feel beyond the surface.

In a moment of collective servitude, which in Italy’s tradition is exemplified by the proverb “o Franza o Spagna, purché se magna,” (France or Spain, as long as we eat), the works that Balaskas offers to us demand of us to look at the cost of that eating, questioning even the value of sitting and watching the end of a summer bliss.

It is for this reason that as a Barbarian, I was ecstatic at the idea of curating a show at the limit of folly. I wanted to be looking from a Barbarian’s perspective at the uncivilized remainders of a civilized world that has cannibalized itself, and is now aestheticizing its imminent death as if it were the death of someone else. A world attempting to acquire the very last amount of capitalistic value, which is supposed to offer a therapeutic final illusion of immortality… It is exactly in this Baudrillardian and nonsensical perception of the illusory that Medea’s gaze becomes a useful tool. Yet, its mythological realism is to be used not to save, but to push further to the edge a world that is collapsing… Shoving it, once and for all, into the depths of its final destiny, and dragging with it all the Neros of this world.

For Medea this was a divine effort, and she had to remind herself that she was a descendant of the Sun God. For Balaskas, it has been a rediscovery of the multiple contradictions of the globalized realities of places that can no longer be recognized. For me it was a rediscovery while writing this essay of my globalized anger towards Italy, my own Mediterranean country, to which I am now estranged while uselessly looking, like Medea, for referential global signposts and alternative loci that no longer exist. The crisis of the Mediterranean has been a global crisis, which, for better or worse, has been setting the stage for a global collapse.

The questions remain unanswered, as does the inability to locate and understand this error through which Mediterraneans continue to repeat a cycle expressing a series of corrupt political classes, one worse than the other, one more fascistic than the other, one more corrupt than the other. Worse, how is it possible that both Fascism and Nazism, incorporated in the rootlessness of a vampiric global neoliberal capitalism or in the tyrannical moralizing superiority of the left, have become such easy exports? This is in total contrast to the attempts, shortsighted and rather naive, of exporting democracy without exporting the ethical context within which it was allowed to flourish.

It is in the collapse of the last vestiges of democracy that we can finally come to the melancholic conclusion that at the end of these summer days there is nothing that is left—this is meant literally, there is no left ideology that has any value. The assimilation of the left to the right, the authoritarian basis upon which the left constructed itself, and how it has run its development has produced what are no longer democracies but oligarchies engaged in selling, before the end of the world, the last breath of life that they can surmise from the pyres of charring bodies convulsing in the last throes of death of their burning cities.

Balaskas’s works constitute an exercise in symbolizing this loss—the aesthetic of the collapse, of the end, and of the transformation of what it was in what it is. They represent the gaze of someone who cannot stand the pain of the last light at the end of the last sunset and yet continues to bathe in that light, feeling the sadness swell with the rising of the waves, whilst being unable to move.

The Mediterranean here is not just a symbolic space of decadence, but—rather—a space of constant decay, where light and shadows, civilized and uncivilized play a role: that of generating the next phase, which will reveal that violence, collapse, and destruction are part of life as much as it is the ability of exercising irony over the most brutal of events—even over our own death…

Watching Balaskas’s works I can imagine being at the end of the day, on the beach, with the last rays of the sun melting in the sea and hearing it… the quick snapping of the thread of life at the hands of Atropo’s knife.

My personal hope is that at the end of this Mediterranean sunset the shadows that are cast, before the final burning of Rome, of Athens, of Istanbul, of Cairo, of Tunis, of Palermo, of Naples, of Berlin, of London, of New York, and Washington are the shadows of a disease carefully injected by the North—that of a nationalistic self-serving neoliberal austerity, if we want to speak in dichotomous terms of North and South—which will quickly spread and leave both the North and the South as the rotten bodies of old gutted whores with the viscera glistening in the dim and cold light of the moon. It is the hope that the rotting and gassing body of this whore of the South will spread the most nefarious plague to remind us that there are no borders for the end of the world.

While preparing this exhibition I could not get out of my mind a summer spent on the island of Buyukada, one of the Prince’s islands, which the people of Istanbul and tourists visit over the summer. It was the end of the day at the end of summer, when I reached a beach after walking through the whole of the island, listening to the singing of the cicadas. There were a few people left and though music was being carried from the restaurant at the bottom of the hill together with the crash of the waves and the gentle whistling of the breeze, the only thing my eyes could see was the litter left behind. Tens of thousands of newspaper pages and plastic bags covered that beautiful Mediterranean brush. They were being lazily moved by the breeze, seemingly trembling at the despair of their own existence and their inability to disappear. The remains of opulent picnics on the side of the sloping hill covered every inch of the ground. All that trash stood against the blue of the sea and the sky, while a red sunset tinged the last of my summer days. The feeling of what humanity was—of what humanity is—was there, and the overwhelming sensation of the futility of existence rose against the certainty offered by the sea, the land, and the sky.

Somehow Medea must have felt like that beach: violated, desolated, and abandoned; as if even the Sun, the Earth, and the Sea had left, and meaninglessness shrouded everything. As if the only thing that she could hear was the rumbling music coming from the restaurant on the beach, mixed with the voice of some underpaid waiter inviting the last customers to their last summer act of consumption.

The roots of this futile act are explored by Balaskas in a distinct body of works presented in Remains of a Summer Bliss. The works are divided in three groups: 1) Failed Economic System, 2) The “End”/ Failure of Utopia / “Revolutionary” Politics, and 3) A World of Fear and Uncertainty.

Failed Economic System

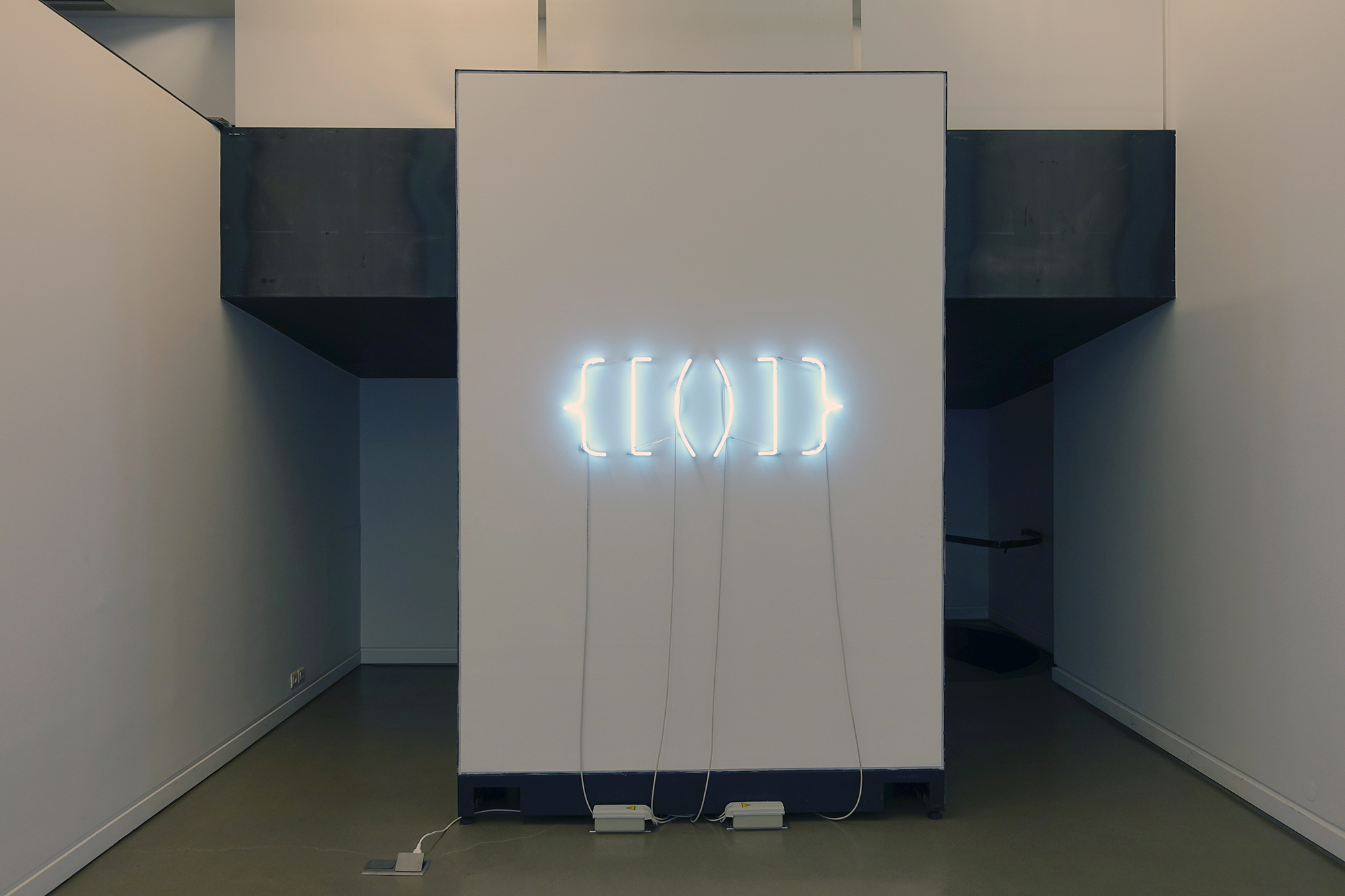

Works: Formula (neon), Flyer, Blanket, Primark.

The end of immortality is embedded in the repeated failure of capitalism which—having finally abandoned the appearance of a collective and egalitarian ideology accessible by all individuals—does not secure immortality, but like Kronos eats its own people and their dreams.

It is the inexorability of loss at the end of a summer bliss in which everyone has consumed and gorged themselves on all that was available and left behind—worse than locusts—the discarded remainders of human existence. The singing of the cicadas is no longer a sound to behold, but it is the sound of jaws chomping and chewing on the bones of the world, constantly consuming everything around and everything inside. It is the cannibalism of past, present, and future all at once and of the whole of it.

Consumption and loss is what we are left with in Balaskas’s exhibition, hidden behind a gentle aesthetic which veils the tragedy of human existence with the melancholy of irony. But as a Barbarian and as a curator with no land and no remorse, I have no excuses and therefore I seek none. I wish no kindness since I have received none. I wish to push the knife further and twist it, via this essay, in ways in which the curatorial experience is not just an articulation of the beauty of the artworks but an analysis of existence—via artworks, aesthetics, and actionism—as a viable last statement for what are the remainders that we contemplate upon.

In the curatorial approach for the staging of the works at the Kalfayan Galleries in Athens the intention of both the artist and the curator was to present a narrative which would offer a conceptual engagement, as well as a passionate and emotive connection with the vision for the show as a staging for the ‘end to come.’ The neon Formula, emptied of any value, remains a completion of nothingness—an abstraction which speaks to the mind of loss at the same time being a container to be filled in by the experience of the viewer. The work of art becomes one of the foci of the exhibition, staged as a flowing narrative and a moment of contemplation.

There was no invitation to a revolution in these works of art. No action to be taken as such, but the artist asked for a deeper re-examination of both our personal experiences and ways of thinking. Primark—the symbol of indiscriminate financial capitalistic consumerism—is an empty bag placed in a plastic vacuum waiting for better times that may never come back. The emptiness of that sealed bag symbolizes the end of an era and of prosperity: no longer will there be flights to London to shop and bring back objects, icons of a mercimōnium of this planet and of the human soul done so lithely and so happily.

The Blanket analyzed another kind of vacuum: that of art, art processes, and artists engaged in constant processes of aestheticization for gain. The capturing of misery becomes another exploitative act, embedded within a larger context, with the stated impossibility of escape but with the opportunity of thinking about the standing of the artist in the light of the sunset with the multiple shadows cast upon the sand.

Of the four works of art that dealt with vacuum, the most empty for me, was Flyer. This particular work of art was empty in its aesthetic since it was embedded, as part of its reality as a found object, in a context of exploitation upon which no other comment could be added or layered on. It boldly and simply presented the vacuum of a society in which the abnormal exploitation has been normalized with an acquiescence that by superseding anger will, at some point soon, become revenge in order to crystallize itself into the violent death of the sun drowned and sizzling in the water to perhaps never rise up again.

The “End”/ Failure of Utopia / “Revolutionary” Politics

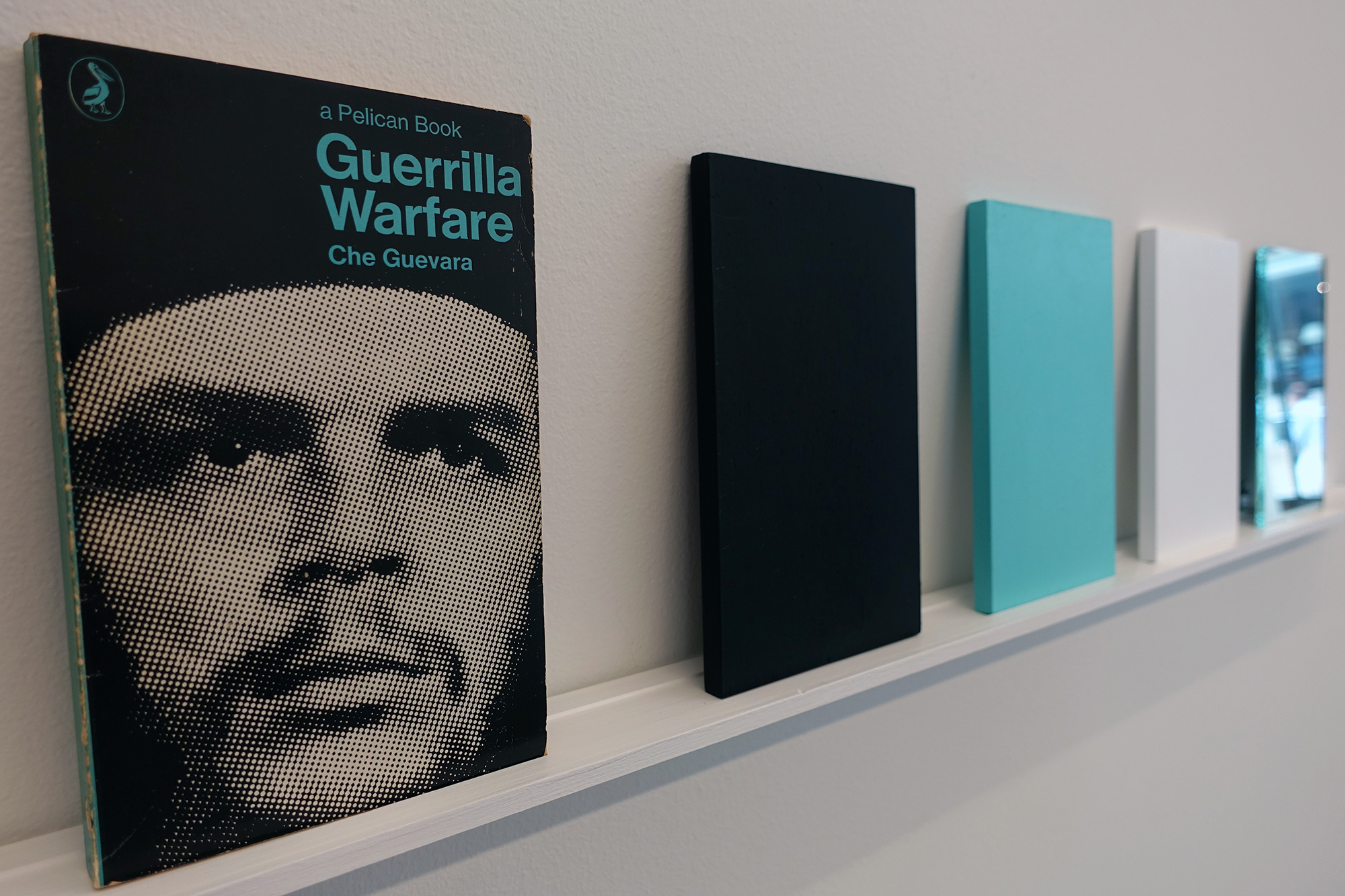

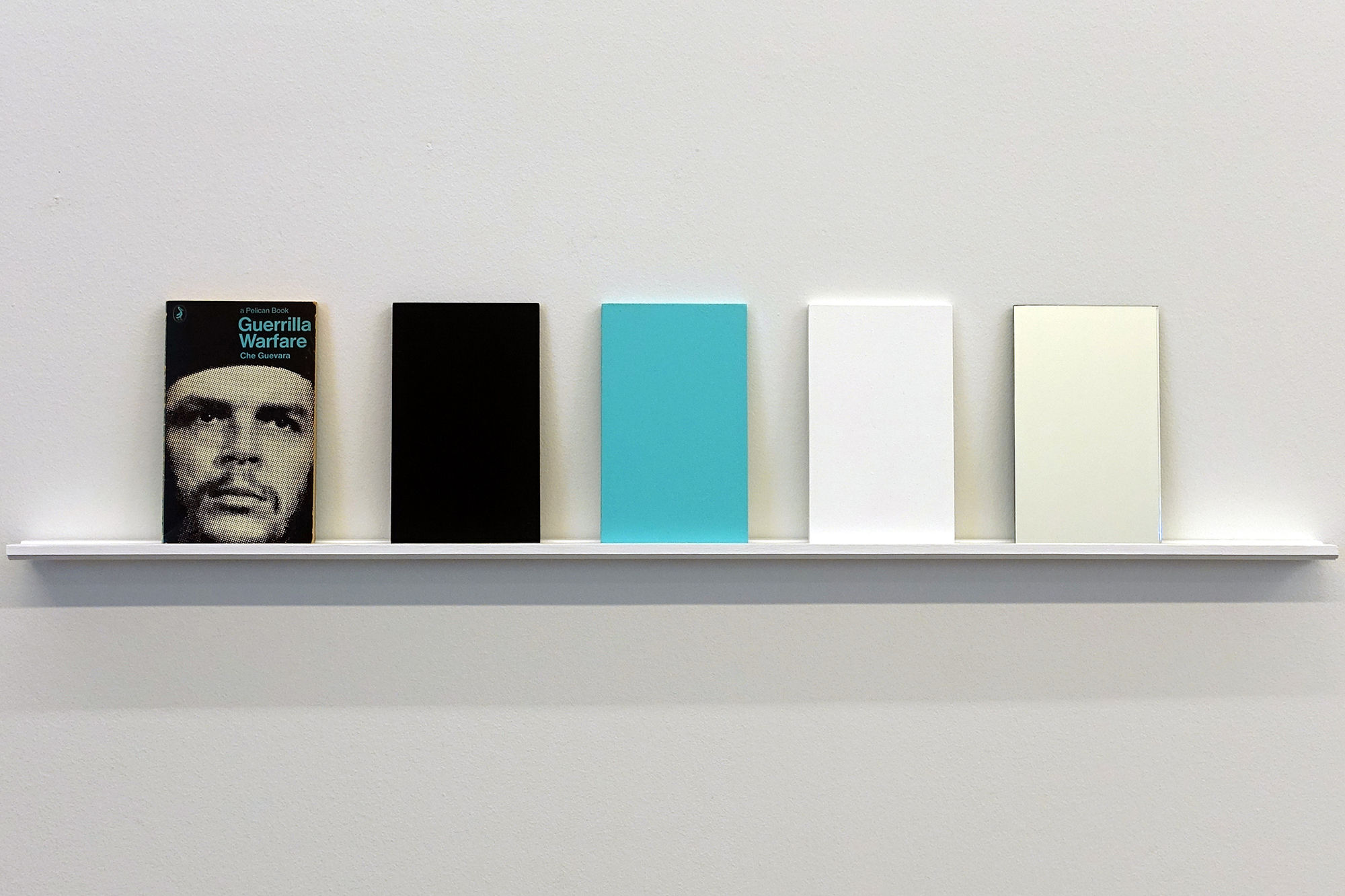

Works: Amaurot (neon), Che Guevara’s book, Megaphone.

The imaginary death of the sun as a metaphor—which is more representative of the death of the viewer—moves the artistic and curatorial discourse away from the emptiness of the previous works of art and points to the meaning of the inheritance of action. The second group of artworks deals, in fact, with actions and their historical inheritance. Is the end really final if there is an inheritance? More importantly, is the consequentialness of action and its long-term inheritance across decades and centuries an eternalizing ethical value of actions?

Balaskas in his approach and construction of the artworks looks at failure as the condition of everything. This is a condition that humanity in its entirety has created via actions which confirm and affirm, as absurd as this may be, the end via people’s final gesture. Actions and gestures are what is left as a philosophical and physical socio-political engagement, but at the same time negate the validity and reinforce the vanity of the inheritance of actions (aesthetic or not) as having any other function but that of bearing witness to the inability of people to act beyond their own short-term interests.

Amaurot is a neon work of art that is located between the tension of the will to exist, the reality of existence, and the utopian dream of a possible existence. The tension of Amaurot is rooted in the very concept of utopia—an unachievable goal that defines both aspirations and realities, and towards which everyone appears to be uselessly striving—which is represented by Balaskas as an ideological and real rot. The lack of correspondence between the capital of Utopia, Amaurot, and the reality of existence is hinted at by Balaskas through a neon sign in which the word rot is visible and readable while the rest of the city of Utopia, the remaining letters that compose the word are switched off. The action of searching for an ideal has become a rot, figuratively and aesthetically. The work obliges the viewer to question the historical inheritance of Thomas Moore, the value of utopianism as a philosophical and ideological movement, and the ideological spawns under various and multi-nefarious utopian flags which have destroyed lives, people, and oppressed nations in name of a divinely—most often—or politically inspired perfection.

Amaurot compels me to reconsider, radically and drastically, the most basic values of the representation of The Ideal City of Urbino—no longer an ideal to strive towards, but a pernicious symbol of the daemon loci. Che Guevara’s book, another of Balaskas’s works that deals with emptiness, is the contemporary representation of the demonic presence which, embedded in a mythology of change and transformation via its actions and inactions, has given birth to a landscape of hypocrisy. No longer eschatological or apocalyptic, but integrated armchairs of revolutionaries, part-time click activists, and Starbucks social warriors, the actions of these people do not sum to nought but actually weigh heavily on the side of consensus and ideological political blindness.

Che Guevara’s book speaks, particularly to my memory, of an all-cannibalizing capitalism supported and promoted by pseudo-radical left wingers who can afford $50 for a designer Che chic t-shirt to bolster their cool status before going back to their mansions. I cannot forget the song “La Cucaracha” blasting from the speakers in a mall where these Che chic t-shirts were on sale for cultural and ideological posers. Capitalism had been able to commodify even its nemesis through ignorance and imbecility. Che Guevara’s book is a work of art that by the deconstruction of its own ontology presents to the viewer the responsibility of existence as action and lays out the actions that have accumulated and achieved the dissolution of a dream, a utopia, and all hope.

What is left of all of these actions—of a Che Guevara’s book that people may not have read but boast of their knowledge of it—is a small mirror. The mirror reflects the image of the viewer and sums up all of the hypocrisies and vacuities in a single visual: the observer as the image of the daemon loci or as the Kafkaesque cockroach: ‘La Cucaracha’.

Megaphone is the natural continuation and seal of approval to the process of acting. Acting—as in making an action—becomes also a theatrical experience in a society in which the action is only validated if it is witnessed, socially mediated, and immediately historicized. The screeching of the cicadas is no longer a sound of remembrance, but a sound to avoid, a sound to escape from, and a sound that announces the end of the summer and the arrival of the season of death. It is the voice of people uselessly screeching and selling their acting as social self-sacrifice and immolation. Aesop’s fable is a harsh warning, a reminder of other seasons to come; and for those witnessing the end of the summer, the sound of the cicadas is a melancholic announcement of things to come. The reflection on the last of the summer days is focused on the actions that should have been taken, those that have been avoided, and those that one wished had been taken. More importantly, Balaskas’s megaphone obliges us to reflect on the acting out of actions as an already heard and seen movie with a stale narrative that can be anticipated at every twist and turn. My personal condemnation of this final action—the enacted masquerading of our inactions— is similar to the repulsion expressed by Dante in the Inferno: there is no justification or melancholia that could soften Minosse’s judgement and the verdict is hell. The song of the cicadas is a reminder of this hell within which the cicadas and their desperate singing symbolize “The struck match of some utopia we no longer remember / the terms of […] here, we stand in our hysteria with our hands in our pockets, / quiet, at the end of day, looking out, theories stationary.” [10]

A World of Fear and Uncertainty

Works: Viewmaster, Globe, Inflatable.

The third and last part of the exhibition focuses on fear and uncertainty. There is an irony that characterizes the works of art and brings levity to the show, reconnecting the various threads. The irony is there to shield the viewer from the pain of the melancholia and of the stark light of reality. Balaskas’s works of art speak of fear without the wish to induce panic. There is no panic button that can be pressed since the inevitability of every event is a given fact. All is already processed, somehow placed in the past, and somewhat historicized even if it has not happened yet. Balaskas offers irony as a palliative to the cynical view of the old world that has seen empires rise and fall. Even if irony is just alleviating the pain of a world terminally ill, nevertheless it allows us to stare into the abyss with great empathy for the victims of the unfolding narratives of destruction. The narratives in this exhibition become the object of terror, while the objects act as referential points of irony and melancholy. It is this divide which makes it bearable to engage with the objects as iconic symbols of destruction, fear, and uncertainty.

Viewmaster brings us back to 9/11 with a children’s toy, as if the perception of what has happened cannot be understood via the eyes of the adult. The work of art speaks also of the end of the age of innocence, if one ever existed in the United States of America at least for its public, and recontextualizes the drama of the destruction in the ever evolving contemporary reality,—away from a forcefully ignored religious war of civilizations—constantly equal to itself and looped like the images placed in the viewmaster. Looking through those images, gazing through them, and finding them recognizable and somehow speaking of ‘simpler’ times, creates relief, surprise, and angst: relief for the recognition of something familiar, surprise at the idea that those images of destruction could become in a strange fashion reassuring, and angst at the realization of the ungraspable ramifications of the original events, which continue to spawn consequences via our contemporary ever evolving histories. This is all through what could be considered a simple toy.

Globe continues this particular section of the series by playing with the concept of mischief. Globe is no longer on its basis, what is left is the light, which is turned on, and the very strong sensation that all is amiss. That the entire world has disappeared, like a game, and that the reality is that our worlds can actually disappear, leaving behind nothing else but the transparency of emptiness visually replaced by its surroundings. As fantastic and terrorizing as it may be, the disappearance of the world would not necessarily matter to the surrounding environment and the loss of it will not necessarily be missed. That is the real scary thought, the irrelevance of our worlds and of our lives in them. No longer central to the universe the globe, anyone around us, and our very own lives can disappear from the map of contemporary narratives leaving little or no disruption. The vacuum can be quickly filled by other things—which will appropriate the new space by becoming more visible—and absence is barely noticeable.

With an artwork based on the lack of presence, Balaskas is able to convey the physical presence of the world by pointing to its fragility and disappearance.

It is in a world in which all seems to collapse that Balaskas adds Inflatable, a work of art that is both a declaration of surrender but also a ray of hope. The collapse of the events that led to the construction of the utopian world, that is the European Union, will be represented in a not-too-distant future by stamps no longer in circulation and with designs symbolizing distant facts no longer relevant or known.

Nevertheless, Balaskas leaves us with the hope that this collapse can be navigated. It is something that has to be faced up by the individual, lost in a sea of events with no direction or support but children’s inflatable armbands. The viewer is presented with the implausible hope that the collapse of the European Union can be navigated with those inflatable armbands. The near impossibility of the task is the final irony, but one in which hope plays a role, even if it is via irony itself or nearly unbeatable odds. No matter how small the odds, they are enough to allow for a glimmer of hope in the melancholia of the last of the summer days that all is not lost. At least not yet.

At the End

If there is still hope in the artworks of Balaskas it is because he is too gentle in his attempt to still find an exit: logical, moral, poetical, or aesthetic—for the Barbarian writing this there is one remainder: the possibility of sitting on a terrace at the edge of the end of the summer and enjoy watching the world burn without a care if a new one will emerge from the ashes. In a world of failed utopias filled with fear and supposed uncertainties, of dogmatic idiocy, and lack of empathy, this Barbarian is instead aware of the certainty of social injustice and human insignificance, enslavement, and exploitation. What is left is the utopia and hope, not of a dystopian world, but of a vengeful and final destruction no matter who, angel or devil, is delivering it.

It is the blissful time spent in waiting, at the end of the very last one of the summer days, to enjoy the collapse of a humanity based on the idiocy of optimism constructed on the blood and bones of the dead, deaf to the screams of the tortured, and automatically blind—with a quickly diverted gaze—to the sight of the poor. This Barbarian would like to be sitting on that terrace, finally with a celebratory glass of champagne and with a phonograph standing against the horizon playing in the background the voice of Maria Callas screaming Medea’s words of loss to the burning fires.

“Parlami terra, fammi sentire la tua voce. Non ricordo più la tua voce. Parlami sole. Dov’ è il punto dove posso ascoltare la vostra voce. Parlami terra. Parlami sole. Forse vi state perdendo per non tornare più. Non sento più quello che dite. Tu erba, parlami. Tu pietra, parlami. […] Tocco la terra coi piedi e non la riconosco. Guardo il sole con gli occhi e non lo riconosco.”

The loss that Maria Callas speaks of, embodying and channeling Pasolini’s Medea, is one that pits the unknown against the known; one that eradicates an old world before a new one may be acknowledged. The loss in Balaskas’s works of art stems, instead, from the impossibility of recognizing a known world that has been devoured; a world whose discarded remnants we can now see at our beaches, villages, and towns… We can spot them in the melancholic streets of Athens and Rome, in the industrial ruins of Detroit, in the forgotten banlieues of Paris and Brussels, and behind the plumes of smoke rising over Damascus, Istanbul, and Diyarbakir…

Consumption and loss is what we are left with in Balaskas’s exhibition, hidden behind a gentle aesthetic that veils the tragedy of human existence. But, as a Barbarian, I wish to stay on that terrace, looking at those remainders of the burning cities and listening to Callas’s words giving voice to Medea’s tragedy. On that terrace there may be the joy to finally see the civilized Jasons of this world screaming at their all-consuming horror with the no longer unavoidable certainty—at last—that they are no gods, and that the hands of Atropos are reaching for their thread.

And so it is that we are the barbarians standing on those remains. We are the barbarians standing amid what we have built and then demolished. We are the barbarians standing on the very same terrace on which Emperor Nero was standing almost two thousand years ago. There is a glorious light bathing us, warming us, almost making us go blind. Where is it coming from? Is it from the flames of a burning city? Or is it from the final rays of summer?

And there is a knife laying nearby…

Acknowledgments

Thanks for their gracious support for this writing to: The Museum of Contemporary Cuts, Kalfayan Galleries, Athens and Thessaloniki, and the editor Candice Bancheri.

And thanks to Pier Paolo Pasolini for seeing ahead of time what others cannot see today, still.

Author Biography

Lanfranco Aceti is known for his social activism and extensive career as artist, curator, and academic. He is a research affiliate and visiting professor at ACT @ Massachusetts Institute of Technology and director of the Arts Administration Program at Boston University.

As an artist and curator Aceti has exhibited numerous personal projects and public performances at international institutions and biennials and participated in numerous art fairs such as Art Athina, Art International, Supermarket, and Contemporary Istanbul.

As an academic Aceti is the Editor in Chief of the Leonardo Electronic Almanac (The MIT Press, Leonardo journal), for which he has edited more than 12 volumes. He also founded in 2017 Contemporary Arts and Culture (CAC), a platform for art publications and collaborations by MIT Press and Leonardo Journal housed at MIT. He has lectured internationally at prestigious institutions such as Yale, Harvard, RCA, Goldsmiths, and Central Saint Martins.

Notes and References

[1] Jorie Graham, “The Errancy,” in The Errancy: Poems (New York, NY: Ecco Press, 1997).

[2] Nelson, “L’Estate Sta Finendo,” YouTube, September 5, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=miLLcuQw-SY (accessed March 5, 2017). The translation is mine: “Summer is ending / and one year goes away / I am growing up / you know I don’t want to. / On the beach of umbrellas / there aren’t any left…”

[3] Please do not confuse this learning process with the statement of Documenta 2017, followed by Adam Szymczyk’s radio interview, which will go down in history as the most vulgar and idiotic attempt of cultural and aesthetic colonialism the world has ever experienced. Vladimir Balzer, “Reaktion auf Kritik aus Athener Kunstszene,” Deutschlandfunk Kultur, April 7, 2017, http://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/documenta-chef-adam-szymczyk-reaktion-auf-kritik-aus.1895.de.html?dram%3Aarticle_id=383349 (accessed May 7, 2017). Also, see: Artists against evictions, “Open Letter to the Viewers, Participants and Cultural Workers of Documenta 14,” e-flux, April 10, 2017, http://conversations.e-flux.com/t/open-letter-to-the-viewers-participants-and-cultural-workers-of-documenta-14/6393 (accessed May 4, 2017).

[4] Horace, Epistulae, II, 1, 156.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Johnstone Parr, “Shelley’s ‘Ozymandias,’” Keats-Shelley Journal 6 (Winter, 1957): 31-35.

[7] Giuseppe Putignano, “ Capalbio, l’Arrivo di 50 Profughi Fa Discutere la Sinistra. ‘Alcuni Territori Sono Speciali.’ Le Accuse: ‘Ipocriti Radical Chic,’” Il Fatto Quotidiano, August 14, 2016, http://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2016/08/14/capalbio-larrivo-di-50-profughi-fa-discutere-la-sinistra-alcuni-territori-sono-speciali-le-accuse-ipocriti-radical-chic/2974710/ (accessed March 23, 2017).

[8] I think perhaps we can all finally agree that there is no difference between this and that. Orwell showed a long time ago that a ruling class of humans or pigs is just a ruling class and that there is no difference between them. “I myself read Animal Farm as despairing of all politics.” Harold Bloom, ed., George Orwell’s Animal Farm (New York, NY: Infobase Publishing, 2009), vii.

[9] This is visible in Southern Europe but also in the United States of America and across Northern Europe, where the standards of living, the idea of society as a collective participation into the life of the nation state, and the idea of democracy as popular will have all but been abandoned, ignored, or manipulated. What appears to be left are the convulsions of post-societies, post-democracies, and post-citizens.

[10] Jorie Graham, “The Errancy,” in The Errancy (Alexandria, VA: Chadwyck-Healey, 1998), 5.

[11] The translation is mine. “Speak to me earth, let me hear your voice. I no longer remember your voice. Speak to me Sun. Where is the point where I can hear Your voices. Speak to me Earth. Speak to me Sun. Perhaps You are getting lost to never come back. I don’t hear any long what You say. You Grass, speak to me. You Stone, speak to me. […] I feel the earth with my feet and I don’t recognize it. I look at the sun with my eyes and I don’t recognize it.” Earth and Sun in the last phrase are no longer capitalized because they have lost their mythology and have been cannibalized by the realism of capitalism. In the eyes of Medea they are no longer recognizable.

Bibliography

Artists against evictions. “Open Letter to the Viewers, Participants and Cultural Workers of Documenta 14.” e-flux. April 10, 2017. http://conversations.e-flux.com/t/open-letter-to-the-viewers-participants-and-cultural-workers-of-documenta-14/6393.

Balzer, Vladimir. “Reaktion auf Kritik aus Athener Kunstszene.” Deutschlandfunk Kultur. April 7, 2017. http://www.deutschlandradiokultur.de/documenta-chef-adam-szymczyk-reaktion-auf-kritik-aus.1895.de.html?dram%3Aarticle_id=3833499.

Bloom, Harold, ed. George Orwell’s Animal Farm. New York, NY: Infobase Publishing, 2009.

Graham, Jorie. “The Errancy.” The Errancy: Poems. New York, NY: Ecco Press, 1997.

Graham, Jorie. “The Errancy.” The Errancy. Alexandria, VA: Chadwyck-Healey, 1998.

Horace. Epistulae: Book II, Epistle I. 156.

Nelson. “L’Estate Sta Finendo.” YouTube. September 5, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=miLLcuQw-SY

Putignano, Giuseppe. “Capalbio, l’Arrivo di 50 Profughi Fa Discutere la Sinistra. ‘Alcuni Territori Sono Speciali.’ Le Accuse: ‘Ipocriti Radical Chic.’” Il Fatto Quotidiano. August 14, 2016. http://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2016/08/14/capalbio-larrivo-di-50-profughi-fa-discutere-la-sinistra-alcuni-territori-sono-speciali-le-accuse-ipocriti-radical-chic/2974710/.