Sabina Andron

Teaching fellow, Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, United Kingdom

Email: s.andron@ucl.ac.uk

Web: https://sabinaandron.com/

Reference this essay: Andron, Sabina. “Enter the Surface-Interface: An Exploration of Urban Surfaces as Sites of Spatial Production and Regulation.” In Urban Interfaces: Media, Art and Performance in Public Spaces, edited by Verhoeff, Nanna, Sigrid Merx, and Michiel de Lange. Leonardo Electronic Almanac 22, no. 4 (March 15, 2019).

Published Online: March 15, 2019

Published in Print: To Be Announced

ISBN: To Be Announced

ISSN: 1071-4391

Repository: To Be Announced

Abstract

This article uses the concept of interface to discuss the vertical surfaces of the built environment as interactive locations of spatial production and regulation. I use interface as a verb and a noun to define the capacity of urban surfaces to display the multiple making of urban space and various claims to citizenship, in the form of material surface inscriptions.

Using examples from my investigations of surfaces in London, UK, I examine their occupation by inscriptions such as graffiti and street art, to demonstrate how these articulate the interfacing capacity of surfaces. The objective is to develop a discourse around urban surfaces as loci of spatial production and governance, by exploring the theoretical and analytical affordances of the interface. I therefore propose the concept of surface-interface, which I define as a site of spatial production which enables both the regulation and subversion of the image of the city, through a visualization of the power regimes that aim to control it.

The essay proposes an activation and enrichment of the space of the surface through a conceptual alignment with that of the interface, to show how urban surfaces act as portals between public and private property, and between regimes of governance and their visual and material contestations. The paper aims to contribute to conversations about spatial articulations of power and citizenship and add to a growing body of research on urban walls and surfaces as key political spaces of contemporary cities.

Keywords: Surface-interface, urban surfaces, urban inscriptions, urban media, graffiti, visibility, spatial production, image of the city

Introduction

This essay explores the concept of interface from the perspective of disciplines such as urban semiotics, visual culture and legal geography, through the study of urban surfaces and inscriptions. It proposes to use interface theory to interpret the materiality and politics of city surfaces, borrowing understandings of the interface from disciplines such as philosophy, literary theory, architecture, media studies and computer science. [1]

The first part of the paper sets up a dialogue between digital and material urban media, to discuss their mobility and interactivity. Media theory is used together with aspects of urban semiotics, to set up a surface scene where material inscriptions are as fluid, responsive and mobile as their digital, screen-based counterparts. Then, I move to an etymological and theoretical discussion of interface and surface, to demonstrate how the skin of the city is more inter-face than sur-face or, what I call a surface-interface.

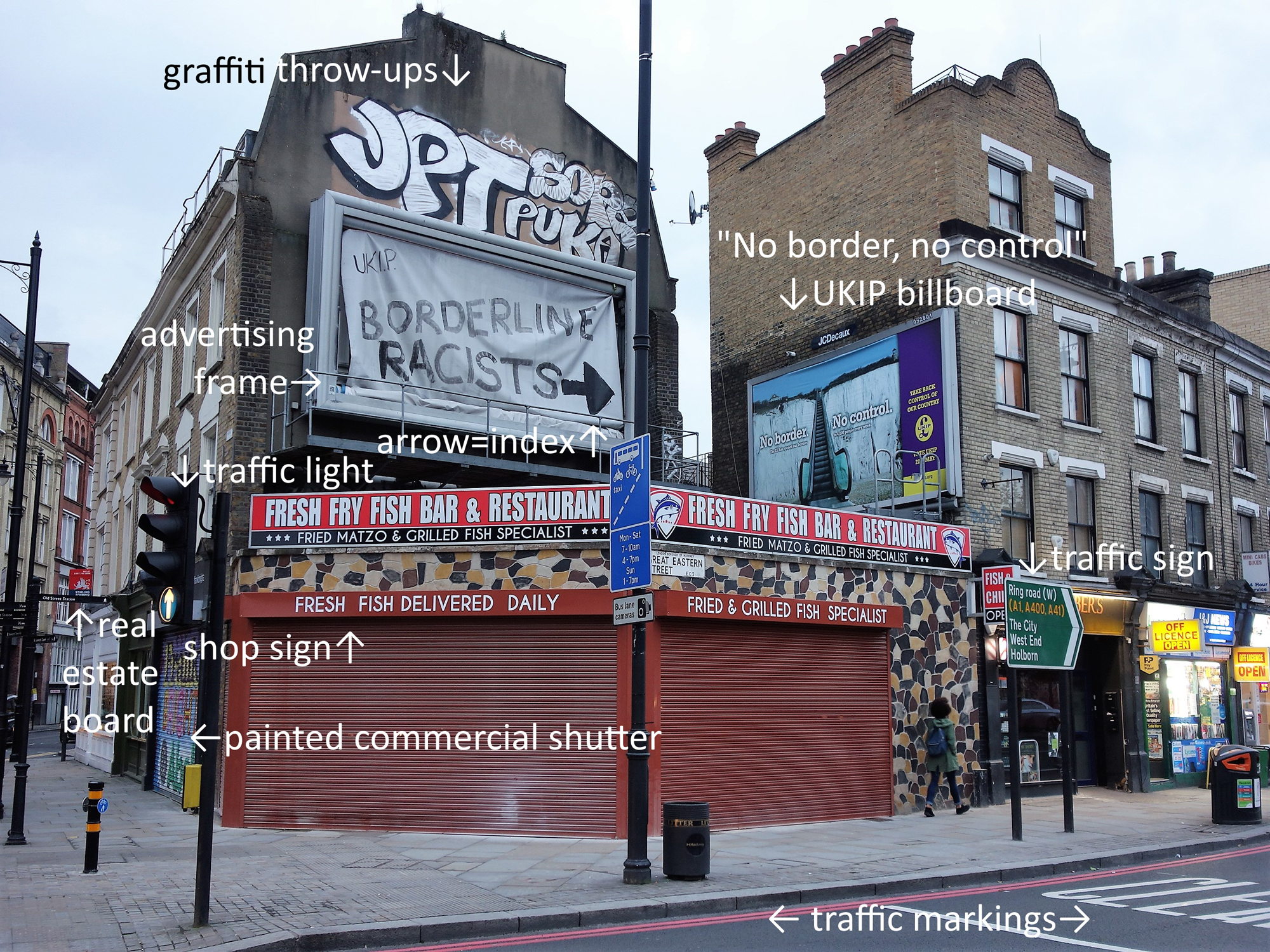

Based on this concept, in the second part, I analyze the surface-interface as a site of visibility, materiality and property, and discuss its support of regulatory and subversive communication in the city. I argue that markings like traffic signs, sanctioned murals and illicit graffiti are productive of publicness and interaction just like digital urban media, and they generate complex communicational hybrids which articulate a surface commons, a plurally produced urban space which is resistant against privatization and exclusion. The argument is illustrated with annotated photographs of urban surfaces, based on a method of surface semiotic analysis I have been developing in my work. [2] In conclusion, I suggest that using digital analytical tools such as the interface can be a useful approach to understand the sitings and entanglements of urban surfaces, and the spatial formations of urban dwelling.

Mobile and Material Inscriptions

The surfaces of cities around the world are hosts to a variety of paper, paint and screen-based media, a concentration of governmental, commercial, artistic and political inscriptions that not only represent, but also constitute urban identities. They are the visible results of ideas about cities, challenges to those ideas, and the policies put in place to manage these tensions. Marks, plaques, traces, scribbles, screens, placards, signboards and inscriptions are visual and material translations of the urban organism, as complex, contradictory, plural and chaotic as the city itself. This is reflected in the increasingly diverse scholarly engagement with urban surfaces and inscriptions, from fields that span visual culture and communication studies to sociology and graffiti studies, to name only a few. [3]

Building on this scholarship, this essay borrows approaches from the study of digital media to examine ‘old,’ material inscriptions, and interpret them as mobile, active agents of urban transformation and surface connectivity. Rather than digital media connecting one place to another, I explore how the material surfaces of the city connect individual claims over the same spaces and store them in publicly displayed archives of signs and inscriptions.

Digital technologies are not part of my argument, but the tools, concepts and vocabulary of digital urban media can be fruitfully used to address material surface displays. This paper is thus approached as an opportunity to explore the concept of interface by looking at non-digital media. There are no screens here, no sensors, no digital data: only walls, inscriptions, and their managed and contested regimes of visibility and regulation. [4] The ambition, then, is to prove that, analyzed together, these elements develop into urban aggregates which look, work and are configured precisely as interfaces.

Nanna Verhoeff, Heidi Rae Cooley and Heather Zwicker define media as “generative, responsive interfaces that invite interaction across their surfaces and, by means of their connections, modify the lived environment.” [5] Similarly, I would propose urban surfaces as everyday media of interaction and regulation: urban walls are the responsive interfaces of the city. The surface-interface is therefore a primary site of social interaction, [6] which produces rich, shared experiences and is a vivid representation of the potential for an urban commons. [7] Surfaces interface between absent authority and everyday inhabitation, between the hard shell of the built environment and the open spaces within it, and between private property and public visibility. Just like digital interfaces, the surface-interface stores a repository of data about the city, its users and their political agendas.

While they tend to appear fixed and semi-permanent, material inscriptions on the surfaces of the city can be read as mobile, interactive media, much like their digital counterparts. They develop and signify as part of a semiotic landscape, [8] where the formation of meaning depends on a network of altering materials, communications and regulations. For example, a billboard poster is subject to content approvals and location rental contracts, while being vulnerable to weathering and to additions that would change its intended message, such as graffiti tags or other scribbles. Similarly, most graffiti inscriptions are exposed to cross-overs and alterations and exist precariously under a threat of lawful removal. Far from being stable and settled, these inscriptions transform and adapt in relation to each other, and to their supportive environments (see Figure 1).

Literature from the fields of urban semiotics, media and communication theory, describes all urban public media as site-specific and connected, including pre-digital wall-based, rather than screen-based messages. [9] With particular reference to digital media, Nanna Verhoeff suggests that it is not technology itself that generates interactivity and connectivity for screens and devices, but it is these media’s capacity of transformation and mobility, that makes them fundamentally interactive. [10] Upon close inspection, the brick-and-mortar surfaces of cities appear just as mobile and interactive as screen-based, digital media, as they are the result of co-production and multiple creation through consecutive gestures of inscription, addition, erasure and subversion. The relation between the regulation and production of city surfaces will come up several times throughout this essay, to illustrate the resilient, interactive and fundamentally public nature of these urban loci.

The idea of local surface communication representing a form of information interface is not new. Historian David Henkin discusses the “flimsy, mobile and ephemeral” signs of mid-19th Ct New York City as testimonies to the frenzy and heterogeneity of modern urban life, [11] while digital scholar Jason Farman speaks of the urban landscape as a site of social interaction. [12] Although he does not explicitly refer to an urban interface, Farman emphasizes the interactive and embodied nature of localized communication in the urban landscape:

From street signs to graffiti and from statues to billboards, cities have used the urban landscape as a site of information. Our embodied interaction with a locale offers insights to the meaning of the place and of our situatedness there. [13]

However, surface-interfaces are not only sites of information: they are also expressive and affective, political and contested. [14] They generate complex materialities and affects through their layered inscription, often despite expectations of cleanliness and order. In his brief history of ‘old’ public media displays such as signboards, placards and billboards, media scholar Erkki Huhtamo recounts that:

Billposters obeyed no rules, using any available surfaces. Layers upon layers, they pasted their broadsides on walls that were often already covered. They competed and even physically fought each other, paying little attention to the official edicts meant to control the situation. [15]

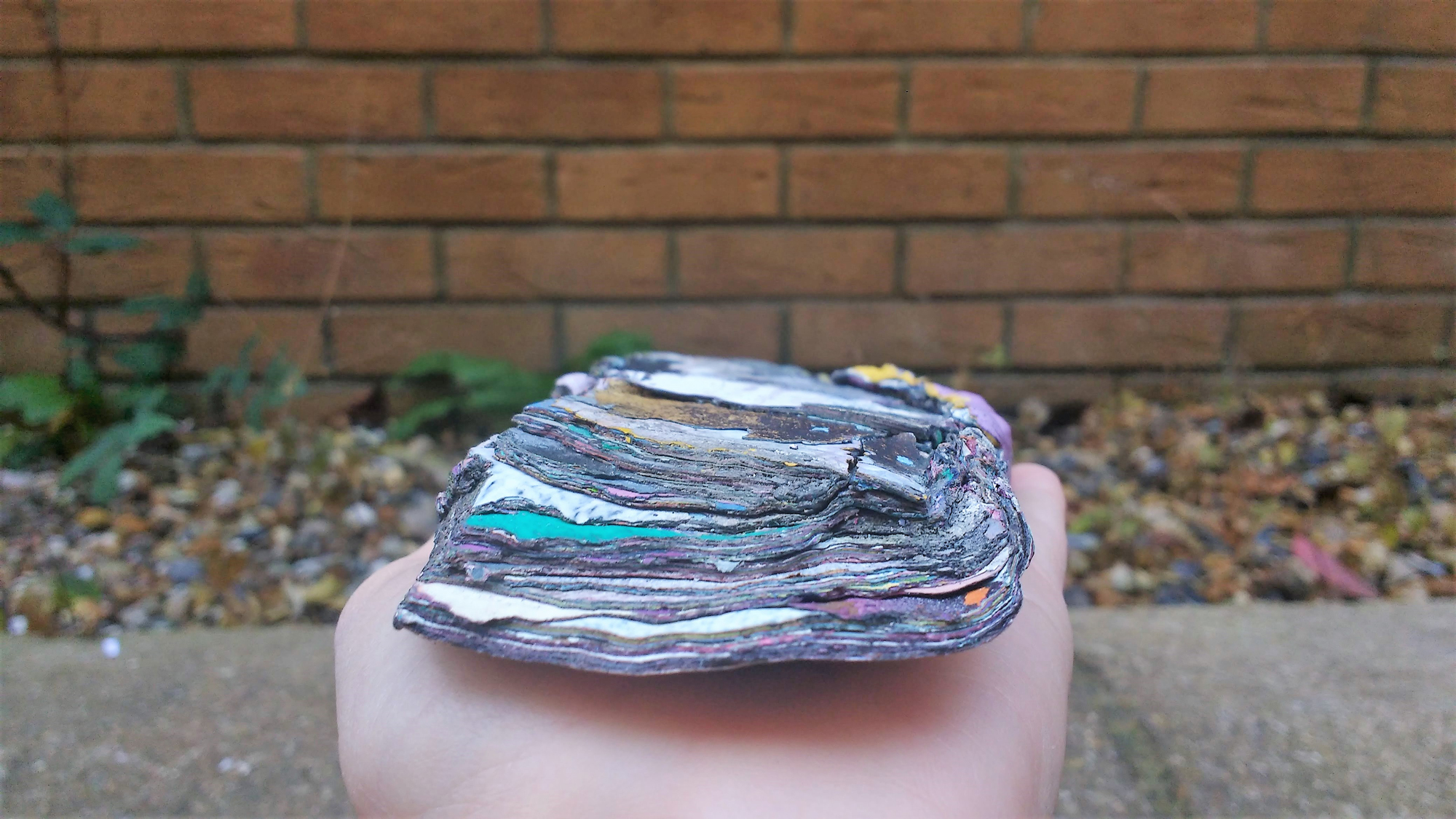

Not only are surfaces primary sites for the battle for urban communication, but they are also material archives of the histories of these battles, thick stacks of forgotten-but-still-present, temporary victories. Verhoeff talks about how urban interfaces make connections to other places, other realities, and especially, other people, [16] where otherness is a function not just of space, but also of time: these material interfaces connect one to others who were there before, who now offer a visible background to display on, textured layers to adapt to, and contentious messages to set up against. Reading material data from city surfaces is therefore not just about the outermost superficial layer, but also about the historical depth of the surface, its previous presentations and occupations (see Figure 2).

The Interface, the Surface, the Relation

Before I discuss some of the signifying dimensions of the surface-interface, I shall dwell for a moment on the etymological differences between surface and interface. These do more than reveal the points of departure between the two types of –faces. They also demonstrate why the skin of the city is more inter-face than sur-face, and why I have chosen to refer to it as the surface-interface throughout this essay.

To begin with, inter– designates occurrences ‘between,’ ‘among,’ ‘in the midst of,’ ‘mutually,’ ‘reciprocally,’ ‘together,’ ‘during’; while sur- expresses supplementation, ‘over,’ ‘above,’ ‘beyond’ or ‘in addition.’ Equally important is the term face, which cultural theorist Branden Hookway defines as that which “is given as available for a reading,” which points outwards and is orientated to the exterior. [17] A sur-face, then, is a facing above or upon a given thing, so a surface refers back to the thing it surfaces, rather than constituting a relation between things. [18] It is the showing of a supplement, the superficial revelation of the expanse that it faces. It also connotes flatness, appearance and lack of depth, like when an approach barely skims or scratches the surface of something. Moreover, Hookway identifies the lack of relation and mutuality as one of the most significant differences between surface and interface: “The interface does not refer primarily to a thing or condition [as surface does], but to the relation between things and conditions, or to a condition as it is produced by a relation.” [19]

In this separation between surface and interface, it would seem that these two spatial conditions are fundamentally opposite: interface is active, while surface is passive; interface is multiple, and surface – mono-articulating; interface joins, while surface only shows; and interface possesses both a behind and a front, while the surface stops at the edge of what is behind it, and does not support a relation between its two sides.

Indeed, the surfaces of neoliberal urban environments are programmed to abide entirely by these definitions. They are there to show, protect and write the social, architectural and governance forces behind them, allowing for a minimum relation to the exterior, publicly accessible spaces of the city. These surfaces are passive displayers of regulatory signage, rentable canvases for consumerist messages, and orderly showcases of governance agendas. They are a spatial articulation of legal constraints and planning permissions, property ownership and construction certifications. [20] Understood this way, surfaces are no more than the hard edge of this authoritative discourse, which inscribes itself dominantly into the fabric of the city and requires these surface spaces to articulate its power. This conception of the surface does not allow for a relation to the ‘other side,’ and it does not support any inter-facing, or multiplicity of discourse.

However, my proposal for the surface-interface is to apply interface theory to the apparently passive surfaces of the city, and arrive at a new understanding of urban surfaces as being fundamentally produced by relations. The surface-interface then becomes the visual and material siting of relations between public and private, between ownership and access, and regulation and dissent. Moreover, it represents a multiple and inclusive condition, a materialization of a communal regime of spatial production and occupation which is not restricted by property certificates or commercial authorizations. [21] City surfaces are relations, and they are made from the multiple voices of cities, both of authority and dissent, of subversion and control.

Vilém Flusser’s discussion of the connections between the two concepts is also useful to develop an understanding of the surface-interface. Flusser defines the interface as a significant surface, “meaning a two-dimensional plane with meaning embedded in it or delivered through it.” [22] Indeed, there are several types of meanings that are articulated in the two-dimensional plane of urban surfaces, all of which are characterized by a necessary spatialization and emplacement: their formation depends on their siting, and they signify through location. [23] Referring to the surfaces of cities, language scholar Alastair Pennycook defines them as integrative and invented environments, not simply canvases or contexts. [24] I have reinforced this discussion myself from a semiotic perspective and have presented surfaces as editable commons and claims to citizenship and the right to the city. [25] In the surface plane, objects can interface with one another and exchange data, as power and its contestations inscribe themselves into the surface-interface in successive layers, which then become part of the materiality of the surface (see Figure 3).

Furthermore, material proximity leads to the formation of new social relations and modes of spatial inhabitation, which was pointed out by Farman in his discussion of the interface. [26] The surface-interface is more than a concentration of materiality and vision; it becomes a form of localized spatial production. Understood as interfaces, the surfaces of the city represent sitings of social relations and they allow for interactions between entities that would otherwise be unable to communicate with each other. [27] These include mechanisms of control and regulation, as well as conditions of social entanglement and exploration:

The interface is a liminal or threshold condition that both delimits the space for a kind of inhabitation [which is so far the operation of surface] and opens up otherwise unavailable phenomena, conditions, situations, and territories for exploration, use, participation and exploitation. [28]

On the one hand, the interface is a surface with an own internal reality and an autonomous aesthetic space; and on the other hand, it is a threshold that facilitates passage and transition, a gateway, a window to some place beyond. [29] Based on this simultaneous passage-blocking and access-granting, Hookway describes a bi-fold system of situations for understanding interfaces. [30] They symbolize separation and unity; they hold apart and draw together; confine and open up; discipline and enable; exclude and include; and maintain and elide distinction. These binary ontologies are equally applicable to the urban surface, whose status is suspended between protection and display; law and subversion; secrecy and exposure. Surfaces interface between distinct urban property regimes and are simultaneously their sites of subversion; and they are more than the sum of their displays and affordances, their official and independent graffiti. The surface-interface allows passage deeper into its layers, into the meanings of occupation, visibility and entitlement. The accumulation of surface inscriptions is the materialization of urban politics.

Presenting the Surface-Interface: Materiality and Visibility

The surface-interface is a significant dimension of urban visibility and is constituted by multiple relations of perception and power. Connections between urban surfaces, visibility and politics are the concern of recent sociological and geographical scholarship. [31] In their discussion of walls and public communication, sociologist Andrea Mubi Brighenti and Urbanist Mattias Kärrholm propose that “if walls have to do with a politics of visibility, it is because and insofar as they are, in the first place, material and semiotic technologies of inter-visibility management.” [32]

The surface-interface also supports processes of in-visibilization and hiding, or manipulating visibility and publicness. The right to contribute to the image of the city will be carefully guarded and eagerly claimed, [33] because visibility is a form of political agency and control of the public sphere. The more inscriptions are visible on the surface-interface, and the more diverse they are, the richer and more inclusive the public sphere.

What is allowed to be visible and by who, at which vantage points and to what audiences, and what resources are mobilized to make this happen – are all concerns for what Brighenti calls the “complex phenomenon of the field of visibility” (see, for example, Figure 4): [34]

Shaping and managing visibility is a huge work that human beings do tirelessly. As communication technologies enlarge the field of the socially visible, visibility becomes a supply and demand market. At any enlargement of the field, the question arises of what is worth being seen at which price – along with the normative question of what should and what should not be seen. These questions are never simply a technical matter: they are inherently practical and political. [35]

Banal, mundane and sometimes hostile walls are principal sights of exploration for the myriad inscriptions that occupy their surfaces. Vertical structures such as billboards or street signs, hoardings or bus shelters, electricity boxes or doorways, are all semantically significant in the configuration of the surface-interface. They open the built structures of the city as potential sites for knowledge transmission and networking, and for political affirmation through the occupation of space. In Lorri Nandrea’s words:

[…] these walls are not simple horizontal borderlines dividing up space; they are vertical planes that, through inscription, can be transformed into unexplored and multidimensional spaces, becoming frontiers in the dictionary sense of ‘undeveloped areas or fields for discovery or research.’ [36]

Similarly, the complexity of surface materials reveals just how deliberately many surfaces are coated particularly to prevent inscription, and to give property owners and authorities a head start in the power balance of surface occupation. It is increasingly difficult to create any undesirable mark, to stick, paint, scratch or write on these geared-up spaces, as many of them are already designed for exclusion, and have built-in privilege to substantially determine the image of the city. These prevention strategies are often part of a set of Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) practices, whereby unwanted or criminal behavior is designed out of places and offered less opportunity to materialize.

We are familiar with hostile architecture in the form of barbed wire, anti-homeless spikes and anti-skateboarding knobs in cities, but it can also appear at a sub-visible level and still hold considerable influence over ‘unwanted’ behavior. In this case, we can speak about hostile surfaces, territories of adversity which are often not visibly marked (most anti-graffiti coatings are transparent), and which silently attempt to exclude any type of undesired addition or contention. This proves once more how the surface-interfaces of cities are places of power and control, which do not have a ‘natural’ or ‘original’ state. [37]

Surfaces make apparent the workings of regulatory systems through invisible and hostile protective coatings, while bearing the politics of multiple occupation and targeted domination. These relations become apparent when different types of surface conditions and inscriptions are juxtaposed, intensifying the surface-interface (see Figure 5). Hookway discusses the unique nature of this interactive space, which is entirely constituted by this multitude of elements:

The interface is at once passive in that it only comes into being when energy is directed in and through it, and active in that it captures that energy as its own, drawing energies from one entity to channel it into another in the production of a mutual activity that only it can fully describe. [38]

Architect Simon Unwin describes surfaces as interfaces between space that can be occupied and solid that cannot, [39] but surfaces are also sites of occupation themselves. They are hard ‘things’ of legal persuasion and material determination, bordering, screening, supporting or protecting ‘content,’ either beyond them (as is the case with walls or hoardings) or before them (billboards, posters, notice boards). Surfaces are frontiers and liminal spaces, in-between spaces, margins, edges and walls; but they are also partitions that can be shared, and are primary forms of co-habitation of the material world: inscriptions open surfaces into depths of meaning and multiple physical dimensions.

Using the Surface-Interface: Regulation and Subversion

Surfaces are the contested edge of an important legal mechanism of entitlement and exclusion: private property. [40] Ownership of private property is the principal determinant not only of the convention of what cities can look like, but also of the legal foundations that regulate and execute these expectations. Every publicly visible surface has a property status and belongs to someone, whether it is marked as such or not. Under Western neoliberal models, the availability of certain surfaces is strictly connected to their ownership status, as they are carriers of implicit and explicit rules and codes of conduct, permission systems and legal frameworks.

Property is the most standard Western form of connection between law and space, and the ownership model shapes understandings of the possibilities of social life, the ethics of human relationships, and the ordering of the economy. [41] Moreover, ownership is spatial, and it relies on spatial boundaries, such as vertical surfaces. These are bounded by property relations and territories, clear or ambiguous ownership, land leases and customary regulations, razor wires and exposed materials.

Geographer Nicholas Blomley argues that property is deeply social and political, structuring immediate relations between people as well as larger liberal architectures, such as the division between public and private spheres. [42] Property is material and tangible, but it is also social, ideological and political, and it shapes all these spheres. Our understanding of the public and the private determines our understanding of the world, what is allowed, what is proper and where it is proper: we cannot conceive the ‘what’ without grasping the ‘where’: how we can be, where we can be, the traces we are allowed to leave there – are all closely bounded by property and ownership.

However, I wish to argue that urban surfaces have the capacity of subverting the ownership model and constituting a communally produced space. They interface the public and the private, and they are of an ambiguous communal type which has been referred to as an alternative to private (but not public), [43] the grey area between private and public and a type of property which subverts hegemonic power relations and is experienced as something in-between public and private by those who engage with it. [44] Not public, nor private, but communally used; transitional and frictional sites which mediate spatial regulation and use. Envisioned as interactive planes, surfaces become a political imaginary as well as a material aspiration and an organizing tool. [45] They unlock the power regimes inscribed in private property, by simultaneously bearing damage to property, and enabling the formation of a communal space. They are privately owned, but publicly used, in public sight, like an open-source interface of urban production and participation.

Both public and private space are regulated from the surface-interface, which is loaded with signs of prohibition and warning, with instructive and informative messages, and guiding lights, arrows and markings. Legal scholars Joe Hermer and Alan Hunt refer to these as “official graffiti of the everyday” and argue that they represent urban regulatory agents as absent experts, [46] who are the dominating forces molding the surface-interface: “Official graffiti constructs an order of surfaces on which individuals are positioned as objects to be regulated by officially ‘defaced’ surfaces that constantly surround the body in both public and private acts.” [47]

Working from behind the surface-interface, the absent experts aim to take full control of this platform, by imposing legal, administrative and design approaches to surface domination. For example, previously discussed CPTED techniques aim to design-out unwanted inscriptions by using protective transparent coatings, greening, not cleaning (vertical gardens and green walls), or by supporting the production and maintenance of certain types of inscriptions, such as billboards and branded murals. Urban development strategies are put in place to support this administratively, and legal sanctions are imposed for those who disregard official ambitions to control the image of the city. For example, there is a direct connection between the criminalization of inscriptions such as graffiti tags, and the implementation of neoliberal governance regimes based on disorder prevention, privatization, surveillance and exclusion; [48] or between the celebration of street art murals, and the imposition of the creativity agenda for competitive urban economies. [49] Both these approaches regulate and prescribe the management of private property and public order through the control of the surface-interface, whose visibility is a most valued asset.

Control is an essential aspect in the functioning of interfaces, both within and outside the urban environment. Hookway suggests that control needs an interface to materialize and become effective, and urban surfaces can be read as the control interfaces of city governance. [50] A thorough reading of surfaces can therefore decipher the codes of governance, alongside their formation of a particular image of the city:

The agency of the interface cannot yet be termed control, though it opens up the opportunity to control. The interface comes into being prior to control; while it does not necessarily entail control, it is the conduit of control, and control always takes place across an interface of some kind. Control recapitulates the binding together of entities by the interface, albeit in an implicit modelling of the interface as an exterior means of access to the interior process of a condition. [51]

The surface-interface is not only a display of regulations-from-behind and contestations-from-the-foreground, but also an access code into the co-production of urban environments, and the various techniques employed to try and gain unattainable dominance (see Figure 6). Control is exercised through the surface-interface, turning it implicitly into a site of contestation, subversion and manipulation. City surfaces are the hard boundaries of privacy and the exposed edges of ownership regimes, but they also represent the limits of these functions: they can only contain so much, and only protect this far, until this authority is undermined, only to be reclaimed and undermined once more.

Conclusion

A preoccupation with urban walls and surfaces has been increasingly evident in recent scholarship I have referred to throughout this essay. Most notably, I would like to draw out Brighenti and Kärrholm’s edited volume Urban Walls: The Political and Cultural Meanings of Vertical Structures and Surfaces, as well as the special issue of Lo Squaderno on “Surfaces and Materials,” edited by Brighenti and Andreas Phillipopoulos-Mihalopoulos. [52] What these publications reflect, and this essay hopes to contribute to, is a growing interest in examining the vertical surfaces of the city as sites of spatial and political production, where a multiple, more inclusive city can be produced. I have previously referred to this condition as “the right to the surface,” [53] and what I proposed here was a reinforcement of surfaces as relational platforms, through theories of the interface.

The concept of the surface-interface progresses discussions on the function and use of urban surfaces in a number of ways. Firstly, it demonstrates the interactive nature of surfaces and their expressive and regulatory agency, between a number of material, visual, and regulatory forces. Far from simply sur-facing regimes of neoliberal governance through order and control, the surface-interface mediates between these and their contestations, demonstrating possibilities for a plurally-produced urban environment.

Secondly, interface theory proved interesting for the discussion of non-digital media such as inscriptions on walls. These were analyzed through a semiotics of a number of London surfaces, whose inter-signification, layering and complex materiality are important characteristics of wall, rather than screen-based media.

Finally, interface theories add to the multi-disciplinary approaches to the surfaces of cities, alongside explorations from architecture, sociology, geography, anthropology and visual culture. Surfaces are reliable insights into the constraints and affordances of urban environments. Approaching them as interfaces can further our pursuit of increasingly relational, editable and equitable urban environments for all.

Author Biography

Dr Sabina Andron is a London-based architectural historian and urban scholar, with an educational background in literature and visual culture. Her research focuses on creative urban transgression, the politics of the built environment and the right to the city; with particular emphasis on semiotic and legal dimensions of urban surfaces, as well as inscriptions such as graffiti and street art.

Sabina currently teaches at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL, the University of East London and Ravensbourne University. Her previous teaching experience includes modules on the history of London architecture, the history of the home and interior design, and outreach work on graffiti, spatial justice and the image of the city. She was a UCL Grand Challenges grantee and organiser of the international Graffiti Sessions conference in 2014, and a British Council fellow at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2016.

Notes and References

[1]

[1] Florian Hadler and Daniel Irrgang, “Instant Sensemaking, Immersion and Invisibility: Notes on the Genealogy of Interface Paradigms,” Punctum 1, no. 1 (2015): 7-25.

[2] Sabina Andron, “Interviewing Walls: Towards a Method of Reading Hybrid Surface Inscriptions,” in Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City, eds. Kostas Avramidis and Myrto Tsilimpounidi (New York, NY, and London: Routledge, 2017); Sabina Andron, “Paint. Buff. Shoot. Repeat. Re-photographing Graffiti in London,” in Engaged Urbanism: Cities and Methodologies, eds. Ben Campkin and Ger Duijzings (London: IB Tauris, 2016).

[3] In visual culture and communication studies: Giuliana Bruno, Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2014); Victoria Carrington, “I Write Therefore I Am: Texts in the City,” Visual Communication 8, no. 4 (2009); Gunther Kress and Theo van Leeuwen, Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication (London: Arnold, 2001). In sociology: Andrea Mubi Brighenti, “At the Wall: Graffiti Writers, Urban Territoriality, and the Public Domain,” Space and Culture 13, no. 3 (2010); Andrea Mubi Brighenti and Mattias Kärrholm, eds., Urban Walls: Political and Cultural meanings of Vertical Structures and Surfaces (London: Routledge, 2019); Andrea Mubi Brighenti and AndreasPhilippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, eds., “Surfaces and Materials,” Special Issue, Lo Squaderno, no. 48 (2018); Rodrigue Landry and Richard Bourhis, “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality: An Empirical Study,” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16, no. 1 (1997). In graffiti studies: Kostas Avramidis, “Public [Ypo]graphy: Notes on Materiality and Placement,” in No Respect, ed. Marilena Karra (Athens: Onassis Cultural Centre, 2015); Samantha Edwards-Vanderhoek, “Reading between the [Plot] Lines: Framing Graffiti as Multimodal Practice,” in Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City, eds. Kostas Avramidis and Myrto Tsilimpounidi (New York, NY, and London: Routledge, 2017); Jeff Ferrell, “Graffiti, Street Art and the Dialectics of the City,” in Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City, eds. Kostas Avramidis and Myrto Tsilimpounidi (New York, NY, and London: Routledge, 2017); Alison Young, Street Art, Public City: Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2014).

[4] Brighenti and Kärrholm, Urban Walls.

[5] Nanna Verhoeff, Heidi Rae Cooley, and Heather Zwicker, “Urban Cartographies: Mapping Mobility and Presence,” Television & New Media 18, no. 1 (2016): 94.

[6] Jason Farman, Mobile Interface Theory: Embodied Space and Locative Media (New York, NY: Routledge, 2012), 61.

[7] Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Commonwealth (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009); Paul Chatterton, “Seeking the Urban Common: Furthering the Debate on Spatial Justice,” City14, no. 6 (2010): 625-628.

[8] Adam Jaworski and Crispin Thurlow, “Introducing Semiotic Landscapes,” in Semiotic Landscapes: Language, Image, Space, eds. Adam Jaworski and Crispin Thurlow (London: Continuum, 2010); Roland Barthes, The Semiotic Challenge (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1988).

[9] Nanna Verhoeff, “Mobile Media Architecture: Between Infrastructure, Interface, and Intervention,” Observatorio (OBS*) 9 (2015): 72; Ron Scollon and Suzanne Wong-Scollon, Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World (London: Routledge, 2003); Erkki Huhtamo, “Messages on the Wall: An Archaeology of Public Media Displays,” in Urban Screens Reader, eds. Scott McQuire, Meredith Martin, and Sabine Niederer (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2009).

[10] Verhoeff, “Mobile Media Architecture.”

[11] David Henkin, City Reading: Written Words and Public Spaces in Antebellum New York (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1998), 15.

[12] Farman, Mobile Interface Theory.

[13] Ibid., 44.

[14] Alison Young, “Criminal Images: The Affective Judgment of Graffiti and Street Art,” Crime, Media, Culture8, no. 3 (2012).

[15] Huhtamo, “Messages on the Wall,” 17, emphasis added.

[16] Verhoeff, “Mobile Media Architecture,” 75.

[17] Brandon Hookway, Interface (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014), 8, emphasis added.

[18] Ibid., 12.

[19] Ibid., 13, emphasis added.

[20] Anne Bottomley and Nathan Moore, “From Walls to Membranes: Fortress Polis and the Governance of Urban Public Space in 21st Century Britain,” Law and Critique 18, no. 2 (2007).

[21] Fleur Johns, “Private Law, Public Landscape: Troubling the Grid,” Law, Text, Culture 9 (2005); Stavros Stavrides, Common Space, the City as Commons (London: Zed Books, 2016).

[22] Farman, Mobile Interface Theory, 63.

[23] Johanna Drucker, “Humanities Approaches to Interface Theory,” Culture Machine 12 (2011), https://www.culturemachine.net/index.php/cm/article/view/434.

[24] Alastair Pennycook, “Linguistic Landscapes and the Transgressive Semiotics of Graffiti,” in Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery, eds. Elana Shohamy and Durk Gorter (New York, NY, and London: Routledge, 2009).

[25] Sabina Andron, “The Right to the City Is the Right to the Surface: A Case for a Surface Commons (in 8 Arguments, 34 Images and some Legal Provisions),” in Urban Walls: Political and Cultural meanings of Vertical Structures and Surfaces, eds. Andrea Mubi Brighenti and Mattias Kärrholm (London: Routledge, 2019); Sabina Andron, “To Occupy, to Inscribe, to Thicken: Spatial Politics and the Right to the Surface,” Lo Squaderno, no. 48 (2018);

Nicholas Blomley, Rights of Passage: Sidewalks and the Regulation of Urban Flow (London: Routledge, 2011).

[26] Farman, Mobile Interface Theory, 64.

[27] Maria Chatzichristodoulou, Janis Jefferies, and Rachel Zerihan, Interfaces of Performance (Abingdon, UK, and New York, NY: Routledge, 2016), 1.

[28] Hookway, Interface, 5.

[29] Alexander Galloway, “The Unworkable Interface,” New Literary History 39, no. 4 (2009): 931-955.

[30] Hookway, Interface, 4.

[31] Oli Mould, Urban Subversion and the Creative City (London: Routledge, 2015); Susan Hansen and Danny Flynn, “Longitudinal Photo-documentation: Recording Living Walls,” Street Art & Urban Creativity Journal 1, no. 1 (2015); Brighenti, “At the Wall”; Brighenti and Kärrholm, Urban Walls.

[32] Brighenti and Kärrholm, Urban Walls, 2.

[33] Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1975).

[34] Andrea Mubi Brighenti, “Visibility: A Category for the Social Sciences,” Current Sociology 55, no. 3 (2007): 324.

[35] Ibid., 327.

[36] Lorri Nandrea, “‘Graffiti Taught Me Everything I Know About Space’: Urban Fronts and Borders,” Antipode31, no. 1 (1999): 111.

[37] For a comprehensive repository of surface material analysis, see Maurice Whitford, Getting Rid of Graffiti: A Practical Guide to Graffiti Removal and Anti-Graffiti Protection (London: Spon, 1992).

[38] Hookway, Interface, 12.

[39] Simon Unwin, An Architecture Notebook: Wall (London: Routledge, 2000), 36.

[40] Alison Young, “On walls in the Open City,” in Urban Walls: Political and Cultural meanings of Vertical Structures and Surfaces, eds. Andrea Mubi Brighenti and Mattias Kärrholm (London: Routledge, 2019).

[41] Nicholas Blomley, Unsettling the City: Urban Land and the Politics of Property (New York, NY, and London: Routledge, 2004), 3.

[42] Ibid., vxii.

[43] Hardt and Negri, Commonwealth.

[44] Luca Visconti et al., “Street Art, Sweet Art? Reclaiming the ‘Public’ in Public Place,” Journal of Consumer Research 37, no. 3 (2010); Sarah Keenan, Subversive Property: Law and the Production of Spaces of Belonging (New York, NY: Routledge, 2015), 92.

[45] Chatterton, “Seeking the Urban Common.”

[46] Joe Hermer and Alan Hunt, “Official Graffiti of the Everyday,” Law & Society Review 30, no. 3 (1996): 455.

[47] Ibid., 475.

[48] Craig Castleman, Getting up: Subway Graffiti in New York (Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 1982); Tim Cresswell, “The Crucial ‘Where’ of Graffiti: A Geographical Analysis of Reactions to Graffiti in New York,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 10, no. 3 (1992); Jeff Ferrell, Crimes of Style: Urban Graffiti and the Politics of Criminality (New York, NY, and London: Garland, 1993); Joe Austin, Taking the Train: How Graffiti Art Became an Urban Crisis in New York City (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2002); Maggie Dickinson, “The Making of Space, Race and Place: New York City’s War on Graffiti, 1970-the Present,” Critique of Anthropology 28, no. 1 (2008); Kurt Iveson, “Cities within the City: Do-It-Yourself Urbanism and the Right to the City,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37, no. 3 (2013).

[49] Cameron McAuliffe, “Graffiti or Street Art? Negotiating the Moral Geographies of the Creative City,” Journal of Urban Affairs 34, no. 2 (2012); Cameron McAuliffe, “Legal Walls and Professional Paths: The Mobilities of Graffiti Writers in Sydney,” Urban Studies 50, no. 3 (2013); Vanessa Mathews, “Aestheticizing Space: Art, Gentrification and the City,” Geography Compass 4, no. 6 (2010); Sarah Banet-Weiser, “Convergence on the Street,” Cultural Studies 25, no. 4–5 (2011); R. Schacter, “Street Art is a Period, PERIOD: or, Classificatory Confusion and Intermural Art,” in Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City, eds. Kostas Avramidis and Myrto Tsilimpounidi (New York, NY, and London: Routledge, 2017).

[50] Hookway, Interface, 12.

[51] Hookway, Interface, 11.

[52] Brighenti and Kärrholm, Urban Walls; Brighenti and Phillipopoulos-Mihalopoulos,“Surfaces and Materials.”

[53] Andron, The Right to the City Is the Right to the Surface”; Andron, “To Occupy, to Inscribe, to Thicken.”

Bibliography

Andron, Sabina. “Interviewing Walls: Towards a Method of Reading Hybrid Surface Inscriptions.” In Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City, edited by Kostas Avramidis and Myrto Tsilimpounidi, 71-88. New York, NY, and London: Routledge, 2017.

Andron, Sabina. “Paint. Buff. Shoot. Repeat. Re-photographing Graffiti in London.” In Engaged Urbanism: Cities and Methodologies, edited by Ben Campkin and Ger Duijzings, 125-130. London: IB Tauris, 2016.

Andron, Sabina. “The Right to the City Is the Right to the Surface: A Case for a Surface Commons (in 8 Arguments, 34 Images and some Legal Provisions).” In Urban Walls: Political and Cultural meanings of Vertical Structures and Surfaces, edited by Andrea Mubi Brighenti and Mattias Kärrholm, 191-214. London: Routledge, 2019.

Andron, Sabina. “To Occupy, to Inscribe, to Thicken: Spatial Politics and the Right to the Surface.” Lo Squaderno, no. 48 (2018): 7-11.

Austin, Joe. Taking the Train: How Graffiti Art Became an Urban Crisis in New York City. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2002.

Avramidis, Kostas. “Public [Ypo]graphy: Notes on Materiality and Placement.” In No Respect, edited by Marilena Karra. Athens: Onassis Cultural Centre, 2015.

Banet-Weiser, Sarah. “Convergence on the Street.” Cultural Studies 25, no. 4–5 (2011): 641-658.

Barthes, Roland. The Semiotic Challenge. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1988.

Blomley, Nicholas. Rights of Passage: Sidewalks and the Regulation of Urban Flow. London: Routledge, 2011.

Blomley, Nicholas. Unsettling the City: Urban Land and the Politics of Property. New York, NY, and London: Routledge, 2004.

Bottomley, Anne, and Nathan Moore. “From Walls to Membranes: Fortress Polis and the Governance of Urban Public Space in 21st Century Britain.” Law and Critique 18, no. 2 (2007): 171-206.

Brighenti, Andrea Mubi. “At the Wall: Graffiti Writers, Urban Territoriality, and the Public Domain.” Space and Culture 13, no. 3 (2010): 315-332.

Brighenti, Andrea Mubi. “Visibility: A Category for the Social Sciences.” Current Sociology 55, no. 3 (2007): 323-342.

Brighenti, Andrea Mubi, and Mattias Kärrholm, eds. Urban Walls: Political and Cultural meanings of Vertical Structures and Surfaces. London: Routledge, 2019.

Brighenti, Andrea Mubi, and Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, eds. “Surfaces and Materials.” Special Issue, Lo Squaderno, no. 48 (2018).

Bruno, Giuliana. Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Carrington, Victoria. “I Write Therefore I Am: Texts in the City.” Visual Communication 8, no. 4 (2009): 409-425.

Castleman, Craig. Getting up: Subway Graffiti in New York. Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 1982.

Chatterton, Paul. “Seeking the Urban Common: Furthering the Debate on Spatial Justice.” City 14, no. 6 (2010): 625-628.

Chatzichristodoulou, Maria, Janis Jefferies, and Rachel Zerihan. Interfaces of Performance. Abingdon, UK, and New York, NY: Routledge, 2016.

Cresswell, Tim. “The Crucial ‘Where’ of Graffiti: A Geographical Analysis of Reactions to Graffiti in New York.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 10, no. 3 (1992): 329-344.

Dickinson, Maggie. “The Making of Space, Race and Place: New York City’s War on Graffiti, 1970-the Present.” Critique of Anthropology 28, no. 1 (2008): 27-45.

Drucker, Johanna. “Humanities Approaches to Interface Theory.” Culture Machine 12 (2011). https://www.culturemachine.net/index.php/cm/article/view/434.

Edwards-Vanderhoek, Samantha. “Reading between the [Plot] Lines: Framing Graffiti as Multimodal Practice.” In Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City, edited by Kostas Avramidis and Myrto Tsilimpounidi, 54-70. New York, NY, and London: Routledge, 2017.

Farman, Jason. Mobile Interface Theory: Embodied Space and Locative Media. New York, NY: Routledge, 2012.

Ferrell, Jeff. Crimes of Style: Urban Graffiti and the Politics of Criminality. New York, NY, and London: Garland, 1993.

Ferrell, Jeff. “Graffiti, Street Art and the Dialectics of the City.” In Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City, edited by Kostas Avramidis and Myrto Tsilimpounidi, 27-38. New York, NY, and London: Routledge, 2017.

Galloway, Alexander. “The Unworkable Interface.” New Literary History 39, no. 4 (2009): 931-955.

Hadler, Florian, and Daniel Irrgang. “Instant Sensemaking, Immersion and Invisibility: Notes on the Genealogy of Interface Paradigms.” Punctum 1, no. 1 (2015): 7-25.

Hansen, Susan, and Danny Flynn. “Longitudinal Photo-documentation: Recording Living Walls.” Street Art & Urban Creativity Journal 1, no. 1 (2015): 26-31.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. Commonwealth. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009.

Henkin, David. City Reading: Written Words and Public Spaces in Antebellum New York. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1998.

Hermer, Joe, and Alan Hunt. “Official Graffiti of the Everyday.” Law & Society Review 30, no. 3 (1996): 455-480.

Hookway, Brandon. Interface. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014.

Huhtamo, Erkki. “Messages on the Wall: An Archaeology of Public Media Displays.” In Urban Screens Reader, edited by Scott McQuire, Meredith Martin, and Sabine Niederer, 15-28. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2009.

Iveson, Kurt. “Cities within the City: Do-It-Yourself Urbanism and the Right to the City.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37, no. 3 (2013): 941-956.

Jaworski, Adam, and Crispin Thurlow. “Introducing Semiotic Landscapes.” In Semiotic Landscapes: Language, Image, Space, edited by Adam Jaworski and Crispin Thurlow, 1-40. London: Continuum, 2010.

Johns, Fleur. “Private Law, Public Landscape: Troubling the Grid.” Law, Text, Culture 9 (2005): 60-90.

Keenan, Sarah. Subversive Property: Law and the Production of Spaces of Belonging. New York, NY: Routledge, 2015.

Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London: Arnold, 2001.

Landry, Rodrigue, and Richard Bourhis. “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality: An Empirical Study.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16, no. 1 (1997): 23-49.Lynch, Kevin. The Image of the City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1975.

Mathews, Vanessa. “Aestheticizing Space: Art, Gentrification and the City.” Geography Compass 4, no. 6 (2010): 660–675.

McAuliffe, Cameron. “Graffiti or Street Art? Negotiating the Moral Geographies of the Creative City.” Journal of Urban Affairs 34, no. 2 (2012): 189-206.

McAuliffe, Cameron. “Legal Walls and Professional Paths: The Mobilities of Graffiti Writers in Sydney.” Urban Studies 50, no. 3 (2013): 518-537.

Mould, Oli. Urban Subversion and the Creative City. London: Routledge, 2015.

Nandrea, Lorri. “‘Graffiti Taught Me Everything I Know About Space’: Urban Fronts and Borders.” Antipode 31, no. 1 (1999): 110–116.

Pennycook, Alastair. “Linguistic Landscapes and the Transgressive Semiotics of Graffiti.” In Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery, edited by Elana Shohamy and Durk Gorter, 302-312. New York, NY, and London: Routledge, 2009.

Schacter, R. “Street Art is a Period, PERIOD: or, Classificatory Confusion and Intermural Art.” In Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City, edited by Kostas Avramidis and Myrto Tsilimpounidi, 103-118. New York, NY, and London: Routledge, 2017.

Scollon, Ron, and Suzanne Wong-Scollon. Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World. London: Routledge, 2003.

Stavrides, Stavros. Common Space, the City as Commons. London: Zed Books, 2016.

Unwin, Simon. An Architecture Notebook: Wall. London: Routledge, 2000.

Verhoeff, Nanna. “Mobile Media Architecture: Between Infrastructure, Interface, and Intervention.” Observatorio (OBS*) 9 (2015): 71-84.

Verhoeff, Nanna, Heidi Rae Cooley, and Heather Zwicker. “Urban Cartographies: Mapping Mobility and Presence.” Television & New Media 18, no. 1 (2016): 93-99.

Visconti, Luca, John F. Sherry Jr., Stefania Borghini, and Laurel Anderson. “Street Art, Sweet Art? Reclaiming the ‘Public’ in Public Place.” Journal of Consumer Research 37, no. 3 (2010): 511–529.

Whitford, Maurice. Getting Rid of Graffiti: A Practical Guide to Graffiti Removal and Anti-Graffiti Protection. London: Spon, 1992.

Young, Alison. “Criminal Images: The Affective Judgment of Graffiti and Street Art.” Crime, Media, Culture 8, no. 3 (2012): 297-314.

Young, Alison. “On walls in the Open City.” In Urban Walls: Political and Cultural meanings of Vertical Structures and Surfaces, edited by Andrea Mubi Brighenti and Mattias Kärrholm, 39-53. London: Routledge, 2019.

Young, Alison. Street Art, Public City: Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2014.