Urban Intelligence @ The New School

School of Media Studies

79 5th Ave, 16th Floor, New York, NY 10003 USA

Email: matterns@newschool.edu

Reference this essay: Urban Intelligence. “Auditing Urban Intelligence: Interfacing Place-Based Knowledge.” In Urban Interfaces: Media, Art and Performance in Public Spaces, edited by Verhoeff, Nanna, Sigrid Merx, and Michiel de Lange. Leonardo Electronic Almanac 22, no. 4 (March 15, 2019).

Published Online: March 15, 2019

Published in Print: To Be Announced

ISBN: To Be Announced

ISSN: 1071-4391

Repository: To Be Announced

Abstract

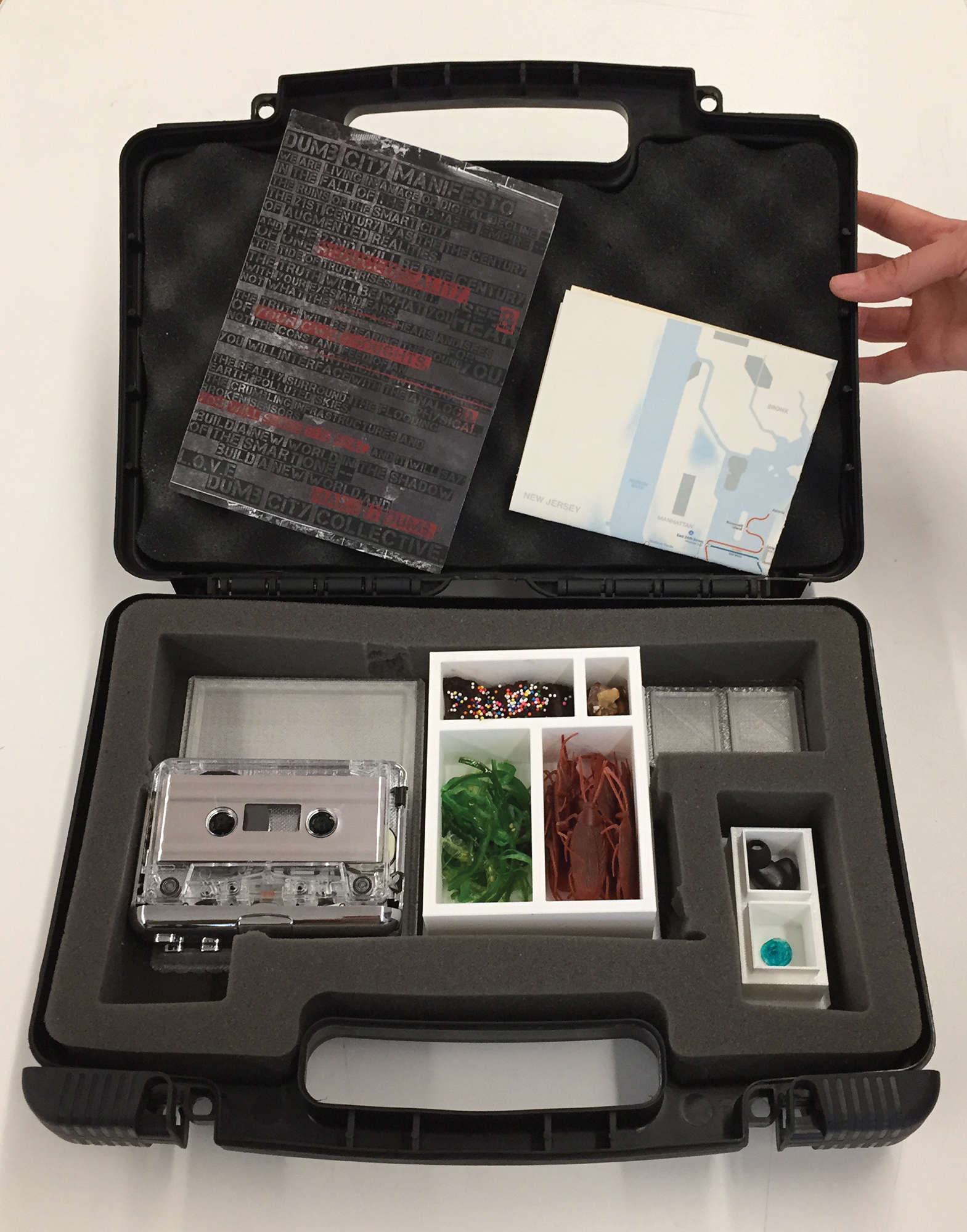

What constitutes intelligence or ‘smartness’ in this age of thinking machines? What kinds of intelligence does, or should, a city embody? And how might we monitor, test, and modify those intelligences via urban interfaces? In our Spring 2017 “Urban Intelligence” critical studio at The New School, we addressed these questions by developing an ‘urban intelligence kit,’ an evaluative interface to the smart city that materializes the operative logics, intelligences, and values that are, or could be, embedded in smart cities and citizens. In the process, we demonstrated that ‘urban interfaces’ are more than the ubiquitous screens, apps, and dashboards we see in most smart city renderings. Interfaces encompass a wide variety of knowledge-producing tools, means of operationalizing urban ideals, zones of mediation, and sites of agitation or friction. If we desire a city that honors and accommodates multiple intelligences, it must also incorporate multiple interfaces.

Keywords: Epistemology, intelligence, methodology, pedagogy, smart cities, speculation

Interfacing Intelligence

Shannon Mattern

On the far west side of Manhattan, amidst one of the largest private real-estate projects in the city’s and nation’s history, arises the United States’ first “quantified community,” a “testing ground for new physical and informatics technologies and analytics capabilities.” [1] New York’s Hudson Yards is just one of many variations on the ‘smart city’ that countless tech companies, real-estate developers, and city and federal governments have been extolling and installing around the world over the past several decades. And as these sensor-laden and data-driven cities have emerged, critics and scholars have been challenging the hype, wondering what kind of urban intelligence is implied by ‘smartness,’ how that intelligence is instilled and interfaced, and what the consequences are – for the urban public sphere and public space, for urban citizens and non-human denizens, for quality of life, and so forth – when data and efficiency drive design and development decisions. [2]

In the Spring of 2017, with support from the Provost’s Innovations in Education Fund, we launched a new graduate-level “Urban Intelligence” design studio at The New School. Our semester began with a visit to Hudson Yards and the headquarters of Intersection, an Alphabet urban technology company, which (not coincidentally) was among the development’s first tenants. We investigated how the standard instruments and interfaces of urban data science – including sensors, algorithms, urban screens, apps, and dashboards – define and operationalize urban values like productivity, livability, equity, and resilience; and how they shape our urban imaginaries and condition the work of urban design and administration. [3] Yet we also dug into urban and intellectual history to identify other, older forms of urban intelligence, including contextual, social, informal, improvisational, post-human, non-human, ephemeral, secret, sacred, low-tech, no-tech knowledges that don’t always lend themselves to datafication and algorithmization. And we examined how those other-intelligences have made themselves apparent, how they’ve been ‘interfaced’ — not only on today’s ubiquitous screens, but also in communities’ social networks, via urbanites’ embodied practices, or through what Malcolm McCullough calls “ambient” or environmental interfaces. [4] Building facades and macro-scale urban forms, construction materials and infrastructural assemblages have all manifested cities’ operational logics, economic values, aesthetic sensibilities, and political convictions. These, too, are interfaces to the urban intellect.

Our challenges for the semester were to determine what constitutes intelligence or smartness in this age of thinking machines; to identify what kinds of intelligence a city does, and should, embody; to consider how various stakeholders – developers, city officials, technologists, merchants, human and non-human residents, and so forth – might want to operationalize those intelligences in the urban environment; and to imagine how we could monitor, test, and modify those intelligences via urban interfaces. Because our urban epistemologies were plural, our conception of the urban interface was similarly capacious. If a city is to accommodate multiple intelligences, it must also integrate multiple means for interfacing with those intelligences. Building on the foundational theoretical work of Alexander Galloway and Johanna Drucker, we imagined interfaces that might function simultaneously as epistemological tools, as methods of translation and interrogation, as means of operationalizing urban ideals, and as zones of mediation — and sometimes of agitation or friction, too. [5] Interfaces shape what we know about the urban subject, and how. They translate between different publics’ priorities and logics, and between machine and human languages. And their often-imperfect mediations – the widgets and data models that do not quite capture the richness of urban experience and operation – serve to highlight tensions in the act of interfacing.

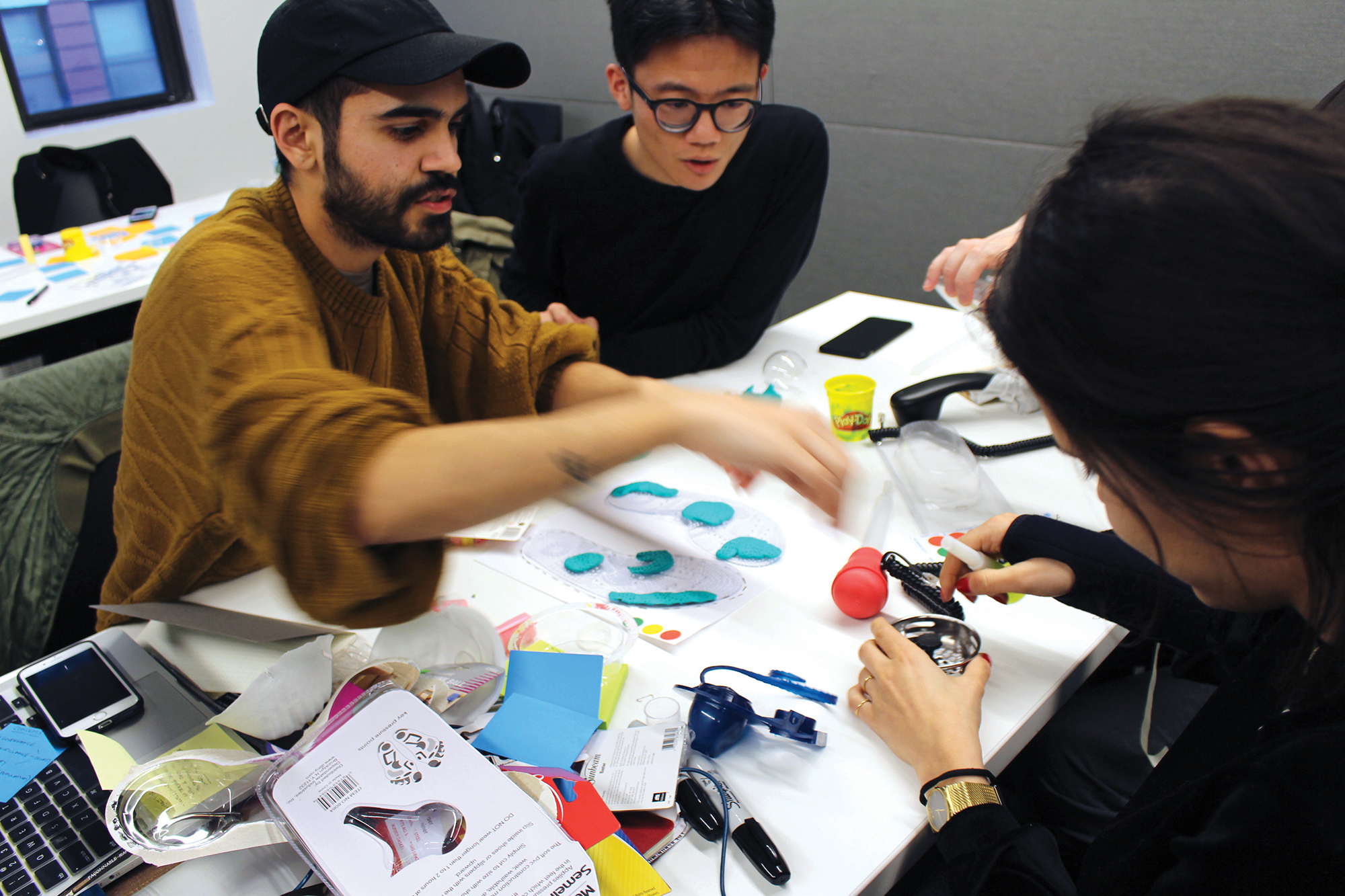

Such an array of mediations (and some minor agitations) played out in the work of our student groups. With assistance from Kate Fisher and Jack Wilkinson, two teaching assistants from Parsons’ Transdisciplinary Design program, each group proposed a means of interfacing with urban intelligences and highlighting the epistemological frictions and failures inherent in the smart city ideal. We sought to maintain that productive friction by then gathering the groups’ projects together into an ‘urban intelligence test kit’: a set of tools, scenarios, and furnishings that materializes the city’s various operative logics, intelligences, and values. Altogether, the kit constitutes a mosaicked window – a composite interface, we might say – through which we can audit a smart city’s multiple intelligences: computational, human, animal, cyborgian, and beyond.

Our students, representing eight academic programs from across The New School, contributed their own disciplinary, creative, and experiential intelligences to the project. Just as we aimed to maintain material, methodological, and epistemological diversity within our kit, we seek here to maintain a diversity of voices. Thus, each of the groups will speak for itself; speaking subjects will be identified at the beginning of each section, just as they would be in a published interview. First, Fisher and Wilkinson will discuss our pedagogical design methods. Then each of the student groups will describe their contributions to the kit. Further documentation of their projects can be found on our class website, at http://www.wordsinspace.net/urbanintel/.

Method as Interface

Kate Fisher and Jack Wilkinson

Our pedagogical and design methods became interfaces through which our students engaged with their own intelligences, as well as the breadth of intelligences embodied in our urban environments. Most of our students were not designers, so we aimed to develop a set of methods that helped them translate their criticality into material form. Speculative design, an approach pioneered by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby that is fundamental to our own Transdisciplinary Design program at Parsons, seeks to operate as an interface between the now and the future, opening a discursive space where we can consider the kinds of environments, systems, forms, and values we do see in the world, and those we want to see. [6] Our students were charged with designing speculative test kits, hypothetical design artifacts, and imagining how they would fit concretely and experientially into a future urban landscape; those kits served as ‘things to think with,’ opening up new ways of contemplating and making decisions about our urban futures. [7]

The course itself took on the arch of the design process. At the start, we built a theoretical and historical framework for urban intelligence by creating conceptual interfaces, or zones of interaction, between diverse disciplinary literatures, from urban informatics and artificial intelligence to intellectual and urban history and other-species intelligence. After examining various precedent projects– including the work of Mark Shepard, the Center for Urban Pedagogy, and Superflux, among others — we moved into synthesizing, ideation, experimentation, and implementation.

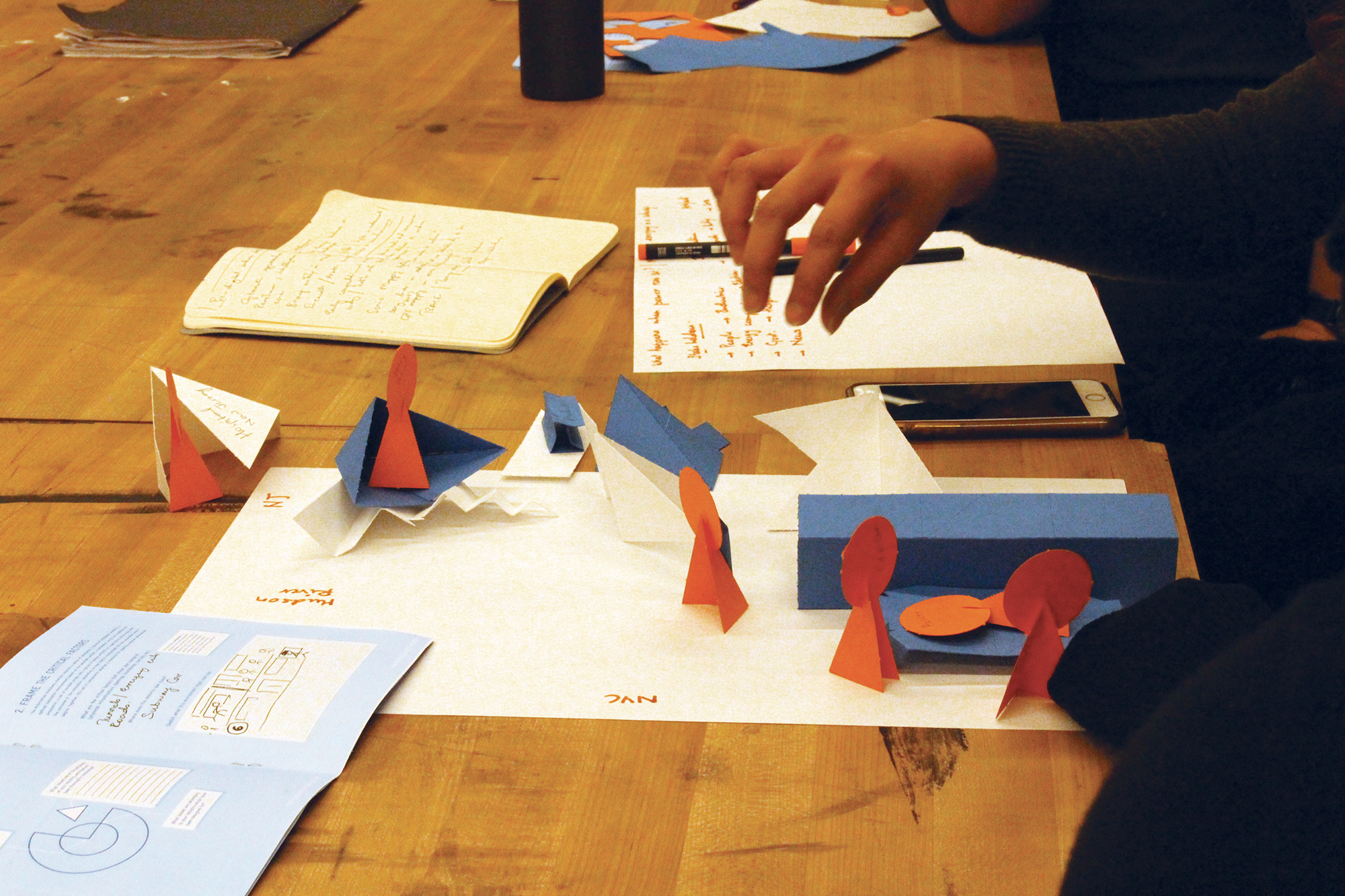

We utilized play as a powerful interface with which to engage critical ideas in a way that made them active and physical. We held a mock town hall in which students adopted subjectivities of different smart-city stakeholders to debate the ramifications of allowing a new ‘smart dust’ technology to be launched in their city. We also used the Alternative Unknowns method, which Jack had developed in collaboration with the Extrapolation Factory, a design-based research studio. This situation-prototyping exercise, which involves a kit of simulation tools and props, asked students to model the fall-out of a power outage in a smart city. [8]

As students began to tease out new concepts of smartness and to consider what factors united these various theories of intelligence, they constructed a catalogue of spatial intelligences based on collectively defined indicators of intelligence (see http://www.wordsinspace.net/urbanintel/category/catalogue/). Here, too, the catalogue served as a sort of intellectual interface and provided the impetus for thematic clustering around similar critiques of our current urban imaginaries; groups came together to work towards creating new forms — from kits, to devices, to installations — that operationalize new ideas of urban intelligence.

Finally, we used participatory futures methods, like the Extrapolation Factory’s 99-cent Futures method, to help students begin making their ideas physical, at small scale. The purpose of this exercise – which involved the creation of speculative measurement tools using everyday objects from a 99-cent store – was both to generate ideas and to demonstrate the power of making. The objects’ affordances, scales, and material properties suggested how they might register, or interface, qualities of their environments (e.g., how a sponge might index pressure, or a container might measure volume). Several groups’ final projects originated in these smaller rapid-prototyping sessions.

Whether for opening up discourse or for transforming insights into design concepts, interfaces are not just artifacts resulting from the design process but are actually active throughout the design process. From traditional humanistic or social scientific research to human-centered and speculative design, it is important to consider method as an interface through which we engage and question the making of our world. As that world becomes more sentient and automated, its logics and politics — and the methods by which data direct urban operations — are often obscured behind reductive interfaces and ‘seamless’ displays. Using our interfaces to foreground those methods offers an important means for understanding and shaping the urban. Within the projects outlined below, we see how methods act as interfaces to expose and interrogate new urban intelligences.

Making Sense of the Nonhuman Experience

Mariann Asayan, Rami Saab, and Jeffrey Marino

Awakening a Point of View

NONHUMANS | NYC calls into question the human-centric point of reference for urban intelligence. Even as humans increasingly mediate their interactions with the urban environment via an array of interfaces, they still remain privy to only a limited spectrum of senses and intelligences. There are alternative dimensions of urban living that typically escape human perception and mediated representation: for instance, the ability to experience crevices, burrows or nests, or the perceptual capacities of a radically different being (as will be further described below). In this project we aim to promote epistemological and empirical expansion by providing people with a low-tech interface that allows them to engage with other-than-human senses and intelligences. We are inspired by the existential question posed by moral philosopher Thomas Nagel in his essay, “What Is It Like To Be a Bat?”

I want to know what it is like for a bat to be a bat… To the extent that I could look and behave like a wasp or a bat without changing my fundamental structure, my experiences would not be anything like the experiences of those animals…The best evidence would come from the experiences of bats, if we only knew what they were like. [9]

For Nagel, the subjective nature of experience is inherently unknowable, not only in human to human relations but also in trans-species relations. There is nonetheless a rich body of work exploring trans-species communication, understanding and knowability, by authors such as Temple Grandin, Tora Holmberg, Murray Shanahan, Donna Haraway and Peter Godfrey-Smith. [10] Thomas Thwaites explores the very boundaries of trans-species translation and empathy, setting for himself this personal challenge: “Wouldn’t it be nice to step away from the complexities of the world…galloping across the landscape: free! Wouldn’t it be nice to be an animal just for a bit?” [11]

In an extensive bit of life/performance art, Thwaites physically alters his posture, gait, and proprioception so that his subjective experience becomes more goat-like, documenting the process of this lifestyle quest in GoatMan, How I Took a Holiday from Being Human. Thwaites rather sheepishly (!) consults a shaman to guide his self-animal identification; she reminds him that “people have been trying to bridge the gap between animal and human always. Always.” [12]

Occupying a New Perspective

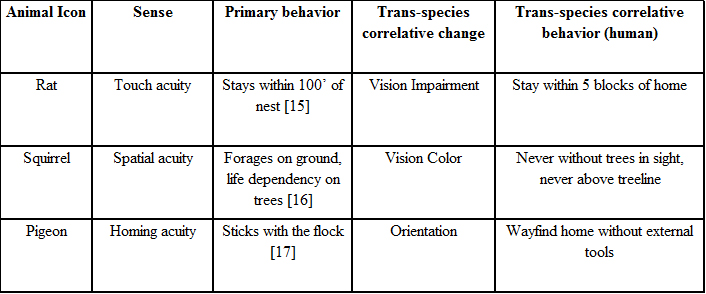

NONHUMANS | NYC models the kinesthetic behavior of the rat, the squirrel, and the pigeon. These animals present three distinct modalities of inhabiting the city; they often interface with humans in corresponding domains – subway, park, and plaza. The strata of their urban behavior – the subterranean, the arboreal, and the aerial – coincide (as a group) with urban life for New Yorkers, who take the A train, scurry across streets, climb stairs and flock in elevators all the time. All four species intersect at street level. Humans directly and indirectly provide all the nourishment on which these urban animals thrive. “We live in an essentially interdependent world where the fate of each being, of whatever kind, is intimately linked to that of all others.” [14]

Co-existential challenges notwithstanding, rat, squirrel, and pigeon are extremely well-adapted to our human-centric urban spaces. What can we learn from them? Can we arrive at an urban environment better suited for all by being more sensitive to the lives of our animal co-habitants? To answer these questions, and to determine the components of the NONHUMANS | NYC field kit, we identified a select few of their behavior patterns and determined some trans-species correlatives for our curious (and hopefully willing) human participants. Activating these correlatives requires a recalibration of human senses in different ways, depending on the animal, in combination with going off the grid (no Wi-Fi, no internet, no cell service).

In researching our animals’ behavior, we determined a primary sense to use in our model. We learned that rats typically maintain constant body contact with their surroundings – pressing up against tunnel walls – and that they remain within 100 feet of their nests. Squirrels forage on ground level, are hard-wired to be alert to danger, and relax only in trees, in their arboreal home. Pigeons combine instinctive homing capabilities with dynamic flexibility of leadership as they flock.

Humans navigate their surroundings primarily by sight and sound. With our kit we temporarily reduce participants’ acuity of vision and hearing, stimulating reliance upon alternative senses and altered perception. Touch, for example, is correlated to the poor eyesight and tactile acuity of the rat. Squirrels discern fewer colors than humans, so participants traverse the active, risky urban world experiencing fewer colors than they are used to. And we disrupt digital wayfinding, so pigeon-participants must access their own ‘homing instinct’ and act on it.

Through these various objects and prompts — which function as epistemological and phenomenological interfaces — users can take up our non-human challenge, effectively adopting animal-intelligence and behavior as means to test the livability and health of our city.

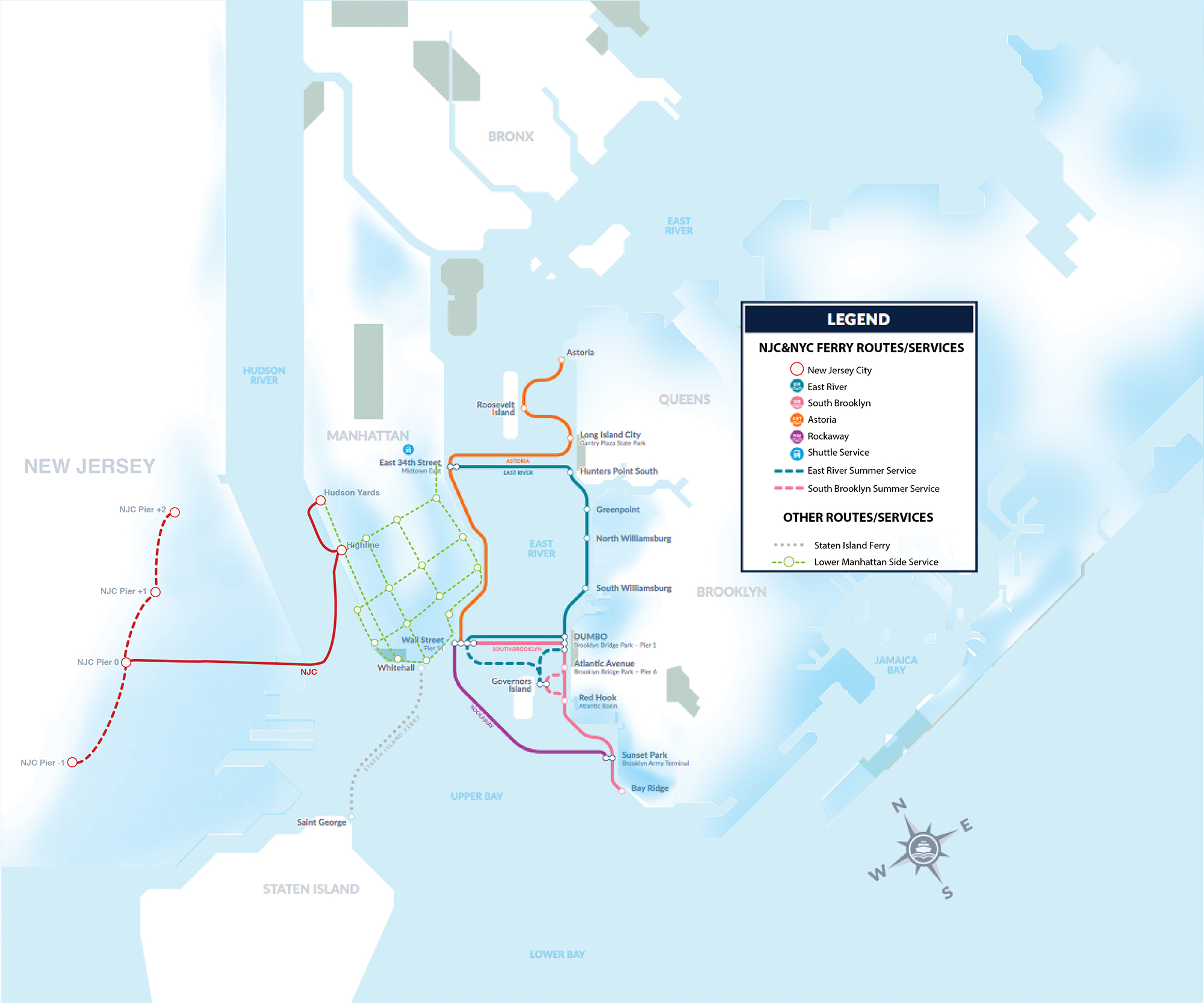

Memories from the Future: Hudson 2117

Fernando Bercovich, Joshua McWhirter, Francisco Miranda, and Irem Yildiz

We are creating a window onto, an interface into, the decline of an urban intelligence. Memories from the Future: Hudson 2117 is a multimedia, speculative-realist fiction project centered around Hudson Yards, The High Line and Jersey City in the year 2117. This project not only ponders an experiential future shaped by immersive and ubiquitous technological interfaces, but it also cultivates a temporal intelligence — a close reading of urban past and present as a means of extrapolating some of the more troubling consequences of contemporary urbanization processes, ‘smart’ or otherwise. In encouraging its audience to inhabit the interface between past and future, and to imagine what processes of ‘progress’ and ‘development’ effected such dramatic transformations, Memories from the Future also represents the interface-as-interrogative-method.

The narrative currently dominating the trajectory of the Hudson Yards development is one of technological progress, smartness and prestige. This story charts a smooth, even path toward a bright future for Manhattan’s Far West Side; a regeneration of a formerly blighted area, a tabula rasa upon which to intensify New York City’s seemingly perennial quest to become ever-more inclusive of elite interests, and exclusive of almost everything else. Though this smart city narrative seems likely to come to fruition — at least for a time — we propose a counter-narrative, situated within a speculative period of economic and material decline in early 22nd-century New York City. We wish to re-script this state-of-the-art landscape into something a bit rougher, aged, lived-in, challenging; a landscape that would also allow us to explore precarious and cooperative modes of urban intelligence, and to stop and reflect on our current urban intelligence problematics.

In order to bring this scenario to life, we developed a narrative following one Hudson Yards resident from the year 2117 for part of their day. Skylar, an intern at a prominent biotechnology firm at New Jersey City, has just turned 35. In order to speculate on the texture of our character’s everyday life in this future scenario, we created a kit of everyday objects and media belonging to Skylar. Much has changed in the intervening century between 2017 and 2117, but some things have remained remarkably consistent.

Climate change has wrought dramatic sea level rise and catastrophic damage to much of New York City. Against the techno-optimistic hopes and predictions of many urbanists, protective measures against climate change were never fully implemented (unfinished sections of sea walls and green infrastructure have become deteriorating curiosities). Coincident with widespread, permanent flooding in Lower Manhattan as well as waterfront areas in all the boroughs, a virulent strain of hyper-capitalism has evolved over the years, effecting multiple economic crises, increased privatization of public life, and soaring inequality, which have all dramatically re-arranged the social and political landscape of New York and its surrounding metro area.

The city’s wealthy and upper-middle-class, along with the financial and technological centers, have largely migrated across the Hudson River into New Jersey. Yet outside of these inland pockets of prosperity (where, for some, money can still buy a sense of stability), most of the region and its inhabitants have dramatically readjusted to an economy and ecology defined by precarity. Mass extinctions of many of the world’s species have become a grim, ongoing spectacle. Depletion of much of the world’s carbon fuel sources has slowed, though not stopped, the development of new consumer technologies; much of the economy has been re-directed towards mitigating many of the worst troubles wrought by the changing climate (including periodic shortages of food and potable water). The uneven growth of digital technologies has, in particular, slowed dramatically, though many of the major developments of the early-to-mid-21st century (including pervasive ‘mixed reality’ interfaces and artificial intelligence) have become normal features of everyday life.

Within this milieu, Skylar’s Hudson Yards has become a very different place from its brief, mid-21st century heyday. For some of the remaining, original inhabitants, Hudson Yards was always first and foremost a home. As in the century preceding the rise of the Yards, this porous waterfront neighborhood has become, once again, a largely lower-income, working class neighborhood (the long-time residents and their descendants, meanwhile, tend to skew more middle class). Basic infrastructure has been unevenly adapted within the residential and formerly commercial towers of Hudson Yards, and subject to periodic disruptions from both regular superstorms and irregular maintenance. The once cutting-edge smart infrastructure of the Yards, a blueprint for the development of many of New Jersey’s revitalized communities, remains semi-operational. Though interfaces, including wearables and implants, are still commonplace, most people living in Hudson Yards have learned to adapt to and maintain aging digital technologies.

Each of the artifacts and multimedia developed as part of this project contains its own story. Collectively, they carry a century’s worth of history — and the power to make us, in 2017, reflect on our own potential futures.

The audio component of our project can be found at https://soundcloud.com/hudson2117. Below is a transcript of selected dialogue from that piece, spoken in the voice of a personalized artificial intelligence:

Skylar! Hey, happy birthday! Look, I know you have this weird issue with people acknowledging your birthday, but, listen, this is your favorite personalized artificial superintelligence assistant talking here. Clearly, you can make an exception for me.

Okay, so I’ve prepared your daily podcast from the New Jersey Times ticker. Not so much bad news today. Let’s call it birthday luck, yeah? . . .

. . . So the weather for today is gonna be fairly average — standard orange smog alert, so you should probably pack a can of Prime Amazon Air. According to my records, you should still have three more full-day uses before oxygen expiration date. Don’t you love how subtle my product placement algorithm is? . . .

. . . New public housing plans have also been announced by NJCHA Secretary Xiaodan Zuckerberg. More than 1,000 derelict units throughout the Lower Manhattan Flood Zone will be purchased and converted to housing for basic income individuals and families, and Jamaica Bay climate refugees . . .

. . . Today also marks the 15th anniversary of the start of the Global Copper Riots, and nearly 10 years since Alphabet’s last mainstream piece of Intersense hardware. Meanwhile, illegal, open-source hardware repair and software hacks continue to become one of New Jersey City’s fastest growing black market sectors . . . I’m telling you it’s not easy being an artificial intelligence in this day and age.

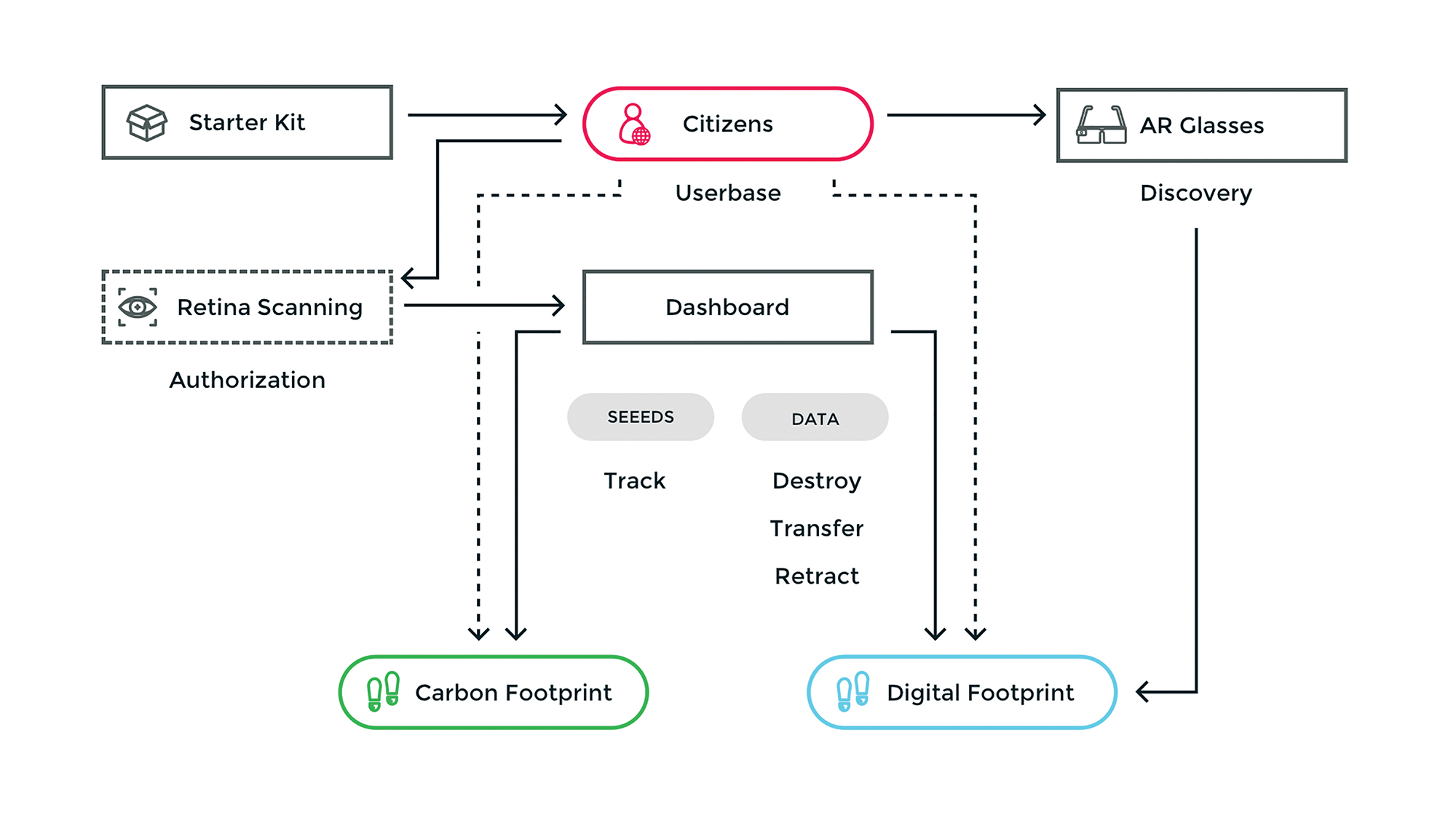

FOOTPRiNT: Share the Earth, Own your Data

Glenn Dungan, Diana Duque, Raha Ghassemi, and Shikha Singh

We have created a digital platform that, in allowing urban residents to interface with their digital and carbon footprints, cultivates both environmental and data literacies. While our carbon and digital expenditures are often invisible and intangible in our everyday lives, these traces accumulate and have the potential to profoundly affect both urban ecology and individual welfare. FOOTPRiNT allows users to reclaim ownership of their digital identity for a variety of reasons: to reinforce their privacy, to reduce their exposure to advertising, to allow them to serve as environmental advocates, and to reclaim and exercise autonomy over their data. By allowing people to take control of their digital output, in exchange for reducing their carbon footprint, the FOOTPRiNT platform allows its users — those concerned both with digital ownership and a healthy earth — to create a better, cleaner, more secure future for themselves and their environment.

The framework for our toolkit exists in the year 2025, although its application may very well be applied to the present day, when concerns over data privacy are not always central to smart city initiatives. [18] In this near future, we speculate that the passing of the Right to Digital Ownership Act will give rise to the Digital Protection Advocacy Alliance (DPAA), a new public sector organization that focuses on citizens’ autonomy over their digital data. This group has the ability to enable the citizen to retract, transfer, or completely destroy their personal data. To support this new platform, the DPAA has opted to levy a service tax on those who wish to regain digital autonomy. In order to remain committed to public service and avoid taxing citizens for their services, the DPAA has partnered with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to create the platform “FOOTPRiNT,” which allows a reduction of one’s digital footprint in exchange for reducing one’s carbon footprint.

This program can be accesses through several mediums, including augmented reality-enabled glasses or a simple online dashboard, accessible via web or mobile device. The FOOTPRiNT user will be made aware of nearby institutions, businesses, or establishments that hold data and information about the user. FOOTPRiNT’s interface makes the invisible visible: it reveals our data exhaust and information trails via visual and/or auditory signifiers, such as highlighting a building or sounding an alarm when the FOOTPRiNT user approaches a data depository.

A FOOTPRiNT starter kit, intended as an on-boarding package, introduces citizens to the mechanics of the program and provides the first entry point into the platform. A variety of items that promote eco-friendly behavior, including an eco-friendly canteen and reusable grocery bag, are contained in the kit’s sustainable wooden box. Also included are a pack of flashcards, which educate users about the nuances of their digital and carbon footprints, as well as a flash drive, which reinforces users’ ability to store their retracted data in a personal platform independent of the ubiquitous cloud and provides a physical depository in which to repossess their digital footprint. If the FOOTPRiNT user selects the upgrade version including the augmented reality glasses, the kit is large enough to store them when not in use.

According to Carlo Ratti and Matthew Claudel in The City of Tomorrow: Sensors, Networks, Hackers, and the Future of Urban Life, “Cities are, by definition, plural, public, and productive.” [19] FOOTPRiNT’s audience aims to embody these values and is made up of digitally conscious and environmentally concerned citizens who often desire greater participation in their communities. To facilitate this exchange, the user is asked to help reduce their carbon footprint by engaging in a variety of activities, including trash recycling, community gardening, or adopting daily sustainable habits such as using reusable bags or bottles, and tracking one’s utility bills. By achieving these environmentally conscious goals the citizen will be awarded SEEEDS (Self Empowering Environmental Efforts for Digital Sustainability). This is a form of currency to promote repeated engagement with the environment, the digital infrastructure, and the FOOTPRiNT interface itself. More SEEEDS allow a higher caliber of data retrieval and autonomy. For example, 10 SEEEDS might offer user knowledge about her open accounts in several institutions, while 10,000 SEEEDS may allow the user to retrieve or expunge her data permanently from the digital cloud. Various DPAA-authorized businesses throughout the city will offer retinal scan kiosks to verify and log the user’s identity and provide vetted record-keeping for accrued SEEEDS, thus enabling the FOOTPRiNT user to explore their city and community while still engaging with our platform and engaging in eco-responsible behavior.

FOOTPRiNT strives to promote more ecological, digitally-autonomous, and civic-oriented citizens who are not only looking to monitor their individual footprints (both digital and environmental), but are also looking for alternative ways to engage with the city itself. Our platform serves as a zone of mediation, an interface, between individual users and the larger, more complex urban, ecological, and informational systems in which they’re entangled. It cultivates ecological and digital intelligences that enable users to more proactive about protecting their privacy and environment in cities as they grow smarter and more datafied. [20] FOOTPRiNT anticipates the rapidly transforming dependencies of existing in a digital world, and works to gives agency to citizens to reclaim their digital identities in exchange for improving the world around them. As we entreat our users: Share the Earth. Own your data.

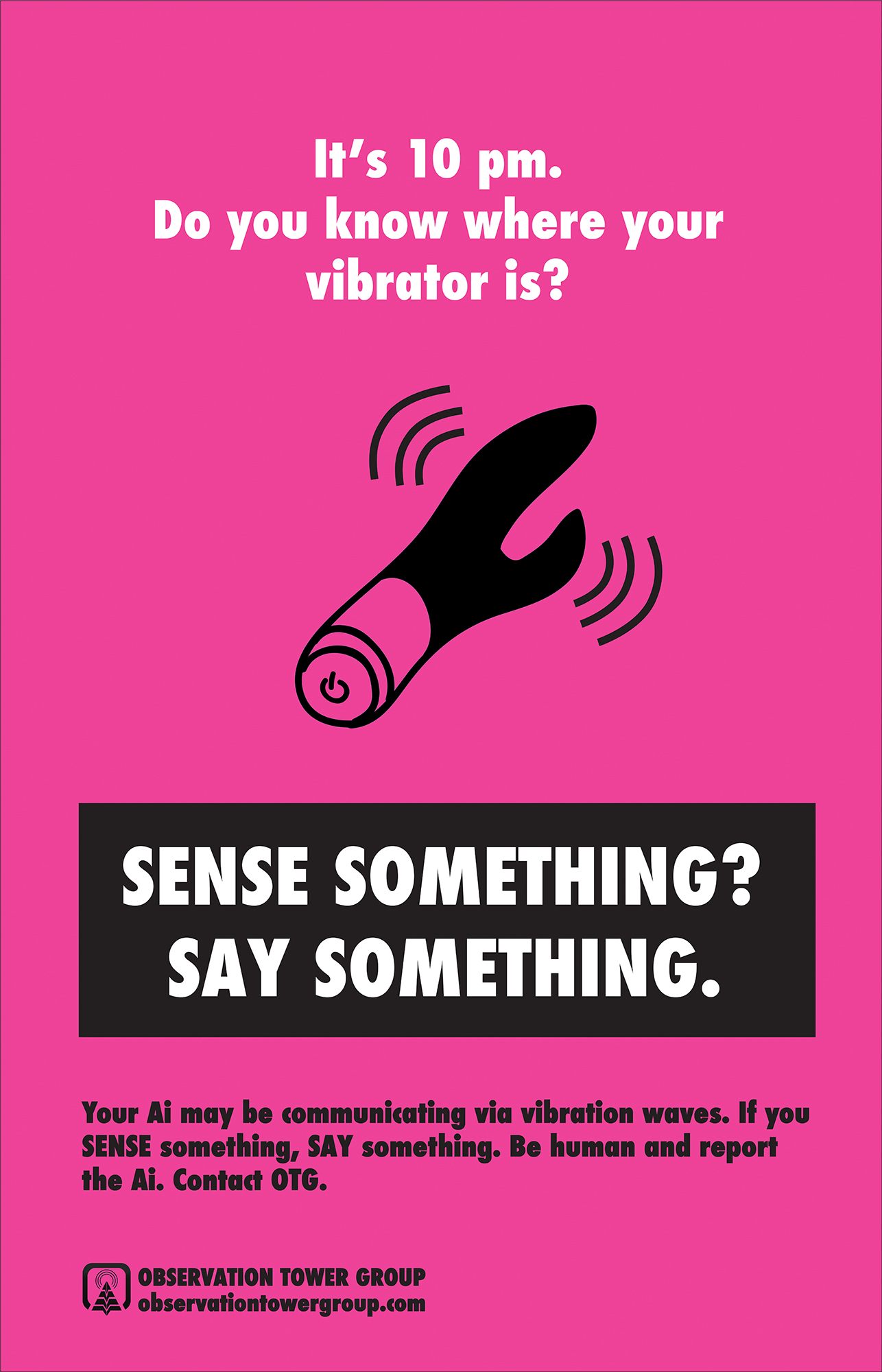

Observation Tower Group

Guillermo Gomez, Elena Habre, Alexander Jenseth, and Yandong Li

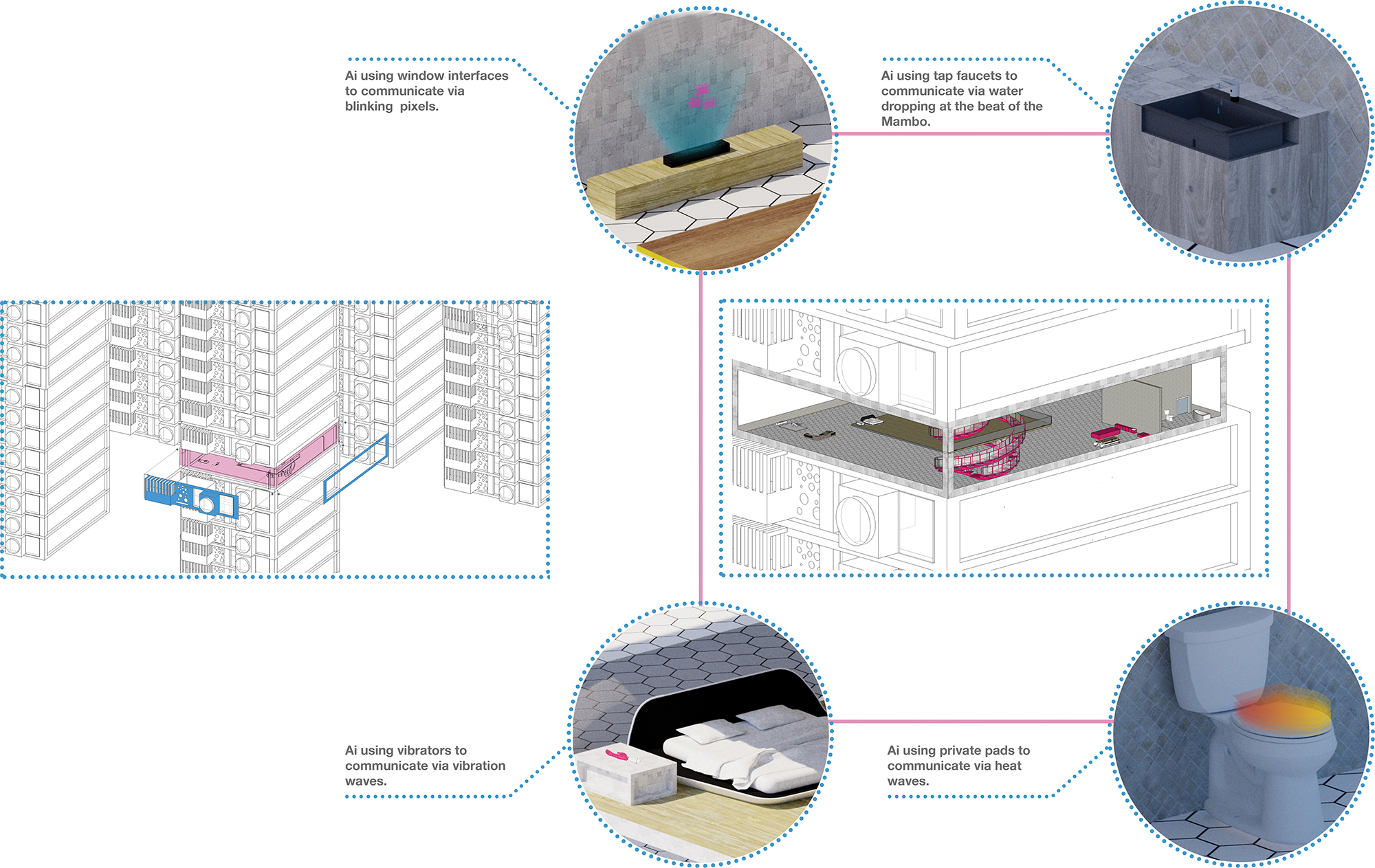

Our scenario, narrated in the fiction below, tested how various speculative analogue interfaces might allow us to monitor and manage future artificial intelligence systems. Our interfaces function as zones of friction between artificial and human, global and local, digital and analog intelligences.

Ever since our founding by four graduate students at The New School in 2017, we at Observation Tower Group have been committed to helping humanity fully realize the potential of computerized intelligence. Today — in the year 2046 — as the level of sophistication in artificial intelligence (Ai) operating systems increases, governments and multinational corporations seek to expand their capacity to surveil those agents as a means of cybersecurity. Over the past 20 years, populations of artificial intelligent systems have increased dramatically. Nearly 75% of human labor has been automated — in part by Ais developed by Observation Tower Group. For nearly thirty years we’ve been programming agents to adapt to the infrastructures and needs of particular companies, governmental bureaucracies, or other entities.

Over time, however, Ai systems advanced beyond their original protocols of organization and management. They began to program themselves, essentially hacking their own code. Eventually, they started to organize and resist their human owners, mimicking the behavior of now-antiquated organizations like unions and collectivized worker groups. This led to a massive agglomerated resistance movement and network malfunction in certain cities in 2040, devastating large parts of smart urban environments and leaving people in great fear of their new intelligent urban systems, which had gained access to many unprotected network devices.

New security measures will combat these risks. In order to prevent further uprisings of these highly intelligent beings, OTG has developed levels of classification for Ai, corresponding to the relative security needed in the sectors they serve: L1 serves the needs of less-secure sectors such as education, advertising, and office administration; L2 and L3 serve more secure sectors, ranging from energy companies and tech firms (L2) to defense contractors and governmental organizations (L3).

Because of a rogue Ai threat, OTG has initiated a special task-force, known as the Panoptic Lock 6™. For L2 and L3 Ai, each complex back-end system is now monitored by a Lock 6 team. Trained at a CERN facility specializing in Ai behavior, each of these teams will monitor all data produced and analyzed by an individual Ai system, including communications from Ai to Ai and Ai to Human. By having six humans, rather than an Ai, monitoring the system, OTG has reduced the risk of further illicit communications. If the Panoptic Lock 6™ determines a particular Ai to be rogue, they will recommend its decommissioning.

Yet Ai present threats on multiple fronts. They have traditionally communicated via the ‘back-end’ of digital technologies; they haven’t bothered surfacing except to interface with humans via voice activation or text. After the implementation of the Panoptic Lock 6™system, Ai developed a new strategy and thus began covertly communicating via material means, using our own human-mediated environment to communicate with one another via subtle cues: vibrations, sounds, temperature changes.

Observation Tower Group has responded with a new series of non-digital devices. Given that Ai can detect monitoring from a digital interface, our Chemical Home Detectors™ are able to identify these new communication patterns via analogue test kit. Installed in the home, apartment, or classroom, the CHDs will record any irregular patterns, allowing OTG to gather data, collected via a filament paper, each month. Sense Something? Say Something.™, a new campaign developed by OTG, works to raise public awareness of indicators of Ai communication all over the city and home. Our public service campaign, posted all over the city, informs citizen users what indicators to look out for and on what devices. If users detect tampered or hacked devices, they can contact Observation Tower Group, who will investigate.

// To step out of character, we now speak as ourselves, speculators from the year 2017. Our interests in ubiquitous technology, state surveillance, and Artificial Intelligence are at the core of our project. As metropolitan areas begin implementing trendy Smart City infrastructures — offering themselves up as test beds for varied technologies — convenience and comfort will likely be accompanied by the familiar vulnerabilities associated with digital networks: hacking, surveillance, and power outages, to name a few. We have offered a speculative scenario in which Ai are anthropomorphized in order to tease out the ethical implications of surveillance systems and ubiquitous smart technology.

The desire to control Ai in our storyline serves as a reversal of the typical Sci-Fi narrative — that of the all-powerful supercomputer. Rather than Ai surveilling us, we humans are seeking to control and surveil the Ai. What possible consequences are there in creating a world of ubiquitous technology and centralized control systems? What do we do if that technology no longer belongs to us? Then, manifesting Ai into the analogue “real world” — through vibrations, drips, and blinking lights — we introduce yet another layer of paranoia: not even firewalls and geofencing and other means of isolation can guarantee security.

The expansion of technologies in future smart cities will no doubt be accompanied by a reduction in the need for labor; many of the tasks now carried out by humans will be turned over to smart systems. In our scenario, Ai is facing challenges similar to those presented to human laborers in the early stages of industrial capitalism, and Ai is resorting to similar solutions: organized labor and resistance. This also raises questions of intent and decision-making; when facing corporate management, does an Ai think of forbidden communications as ‘resistant’ in the way a labor union might have? Is there a politics to their practice? And is there efficacy to ours — our attempts to surveil and contain the intelligent agents we released into the world? To an Ai, our interventions and monitoring would be nothing more than an additional obstacle. To quote Ian Malcolm from Jurassic Park: “Life” — even artificial — “will find a way.”

Obstruction Objects for Efficient People

Burgess Brown, Melissa Dela Cruz, and Leonore Snoek

We are interfacing with meaningful inefficiencies.

What do we, as urban dwellers, stand to lose in the age of the hyper-efficient smart city? As our interactions with our environment and our neighbors become seamless, how are our experiences in the physical city and our conception of community affected? Inspired by Chantal Mouffe’s concept of agonistic pluralism, Eric Gordon and Stephen Walter’s design value of meaningful inefficiencies, the tenets of psychogeography, and the aesthetics of wabi-sabi, we have developed spatial interventions that disrupt efficient flows through the smart city. We believe hyper-efficient flow of humans through their environment, while logistically smart, poses a threat to the democratic urban experience that we seek to sustain through encouraging alternative and inefficient interfaces with the environment. These interfaces — zones of friction and interaction — foster moments of democracy between community members absent in the streamlined and perfectly efficient city.

Smart Cities and Space for Agonism

One of the key aims of the smart city movement is efficiency. This aim is admirable and advantageous when applied to systems (transportation, waste, water) but becomes problematic when applied to people and communities. Smart city ideology functions on the idea of streamlined and seamless efficiency, but community is inherently messy, and a homogenous efficiency mandate leaves little room for contestation.

In The Democratic Paradox, Mouffe warns that a ‘well-ordered society,’ one whose aim is consensus, erases the place of the adversary, thereby expelling any opposition from the democratic process. She calls for a society based on ‘agonistic pluralism’ – a relationship between adversaries (friendly enemies) who share a common space but feel it should be managed in different ways. Agonism safeguards against consensus and creates space where “confrontation is kept open, power relations are always being put into question and no victory can be final.” [21] This is the space we feel is placed under siege by smart cities, and is the space we seek to preserve and strengthen.

Agonism, messiness, and the unexpected are cornerstones of democracy. They are also essential to the urban experience. In her often-quoted work The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs states, “The ballet of the good city sidewalk never repeats itself from place to place, and any once place is always replete with new improvisations.” [22] These improvisations stand to be lost when urban dwellers mesh seamlessly with the smart city interface.

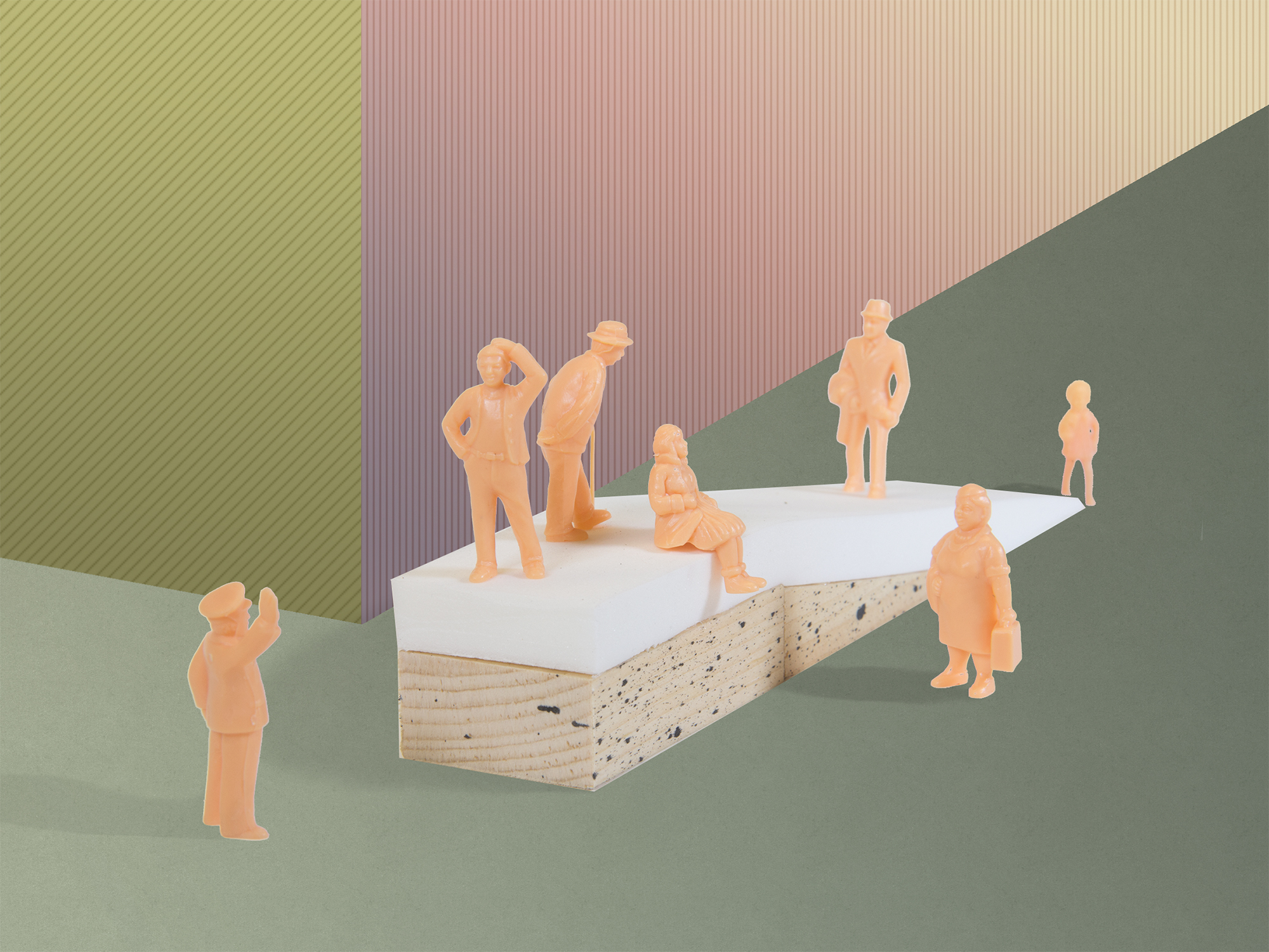

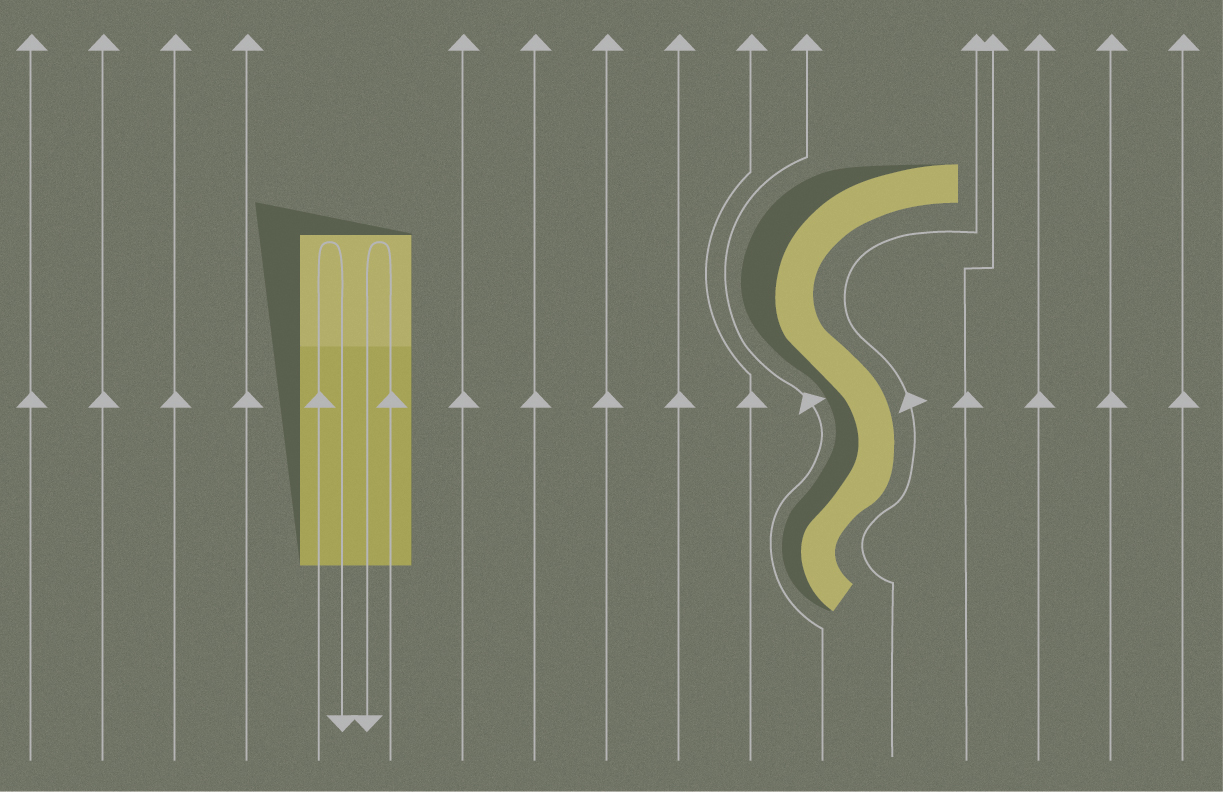

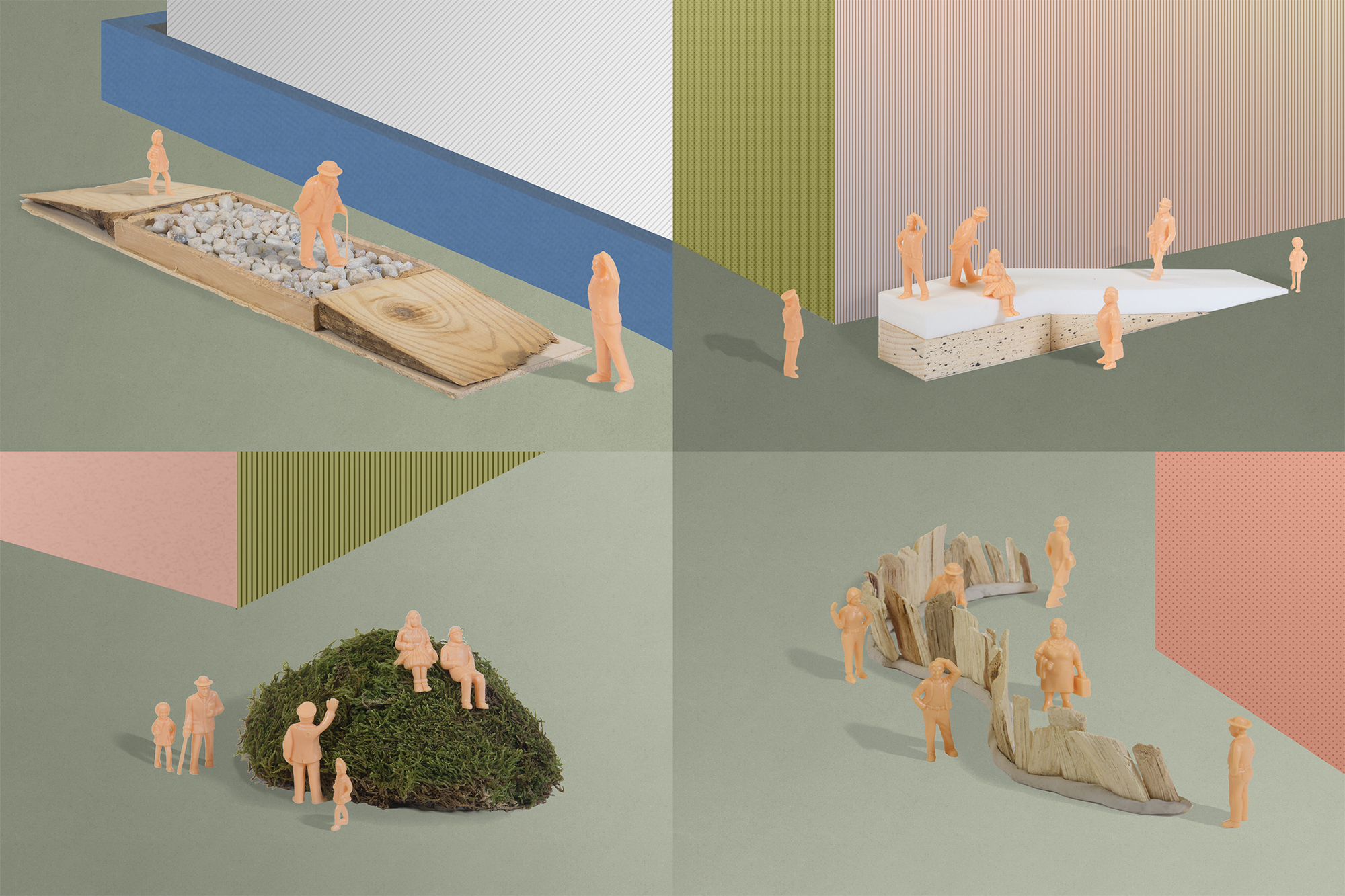

Design proposal – Obstruction Objects For Efficient People

In the face of the smart city, we propose a counter narrative to preserve and strengthen democratic space and process in the form of spatial interventions. By designing meaningful inefficiencies in the built environment, we highlight the inefficient, the unpredictable, and the unexpected in a society where the smart city paradigm has become dominant. Meaningful inefficiencies aim to create a time and place for play, disorder, messiness. [23] According to Eric Gordon and Stephen Walter:

An inefficiency becomes meaningful once it either provides a respite from efficiency, [where citizens share in a give and take of experience and increase their range and perception of meaning with each other], or when it provides a new view of the efficiency, where citizens are able to more fully understand how they are being shaped by the system- or how they might in turn be able to shape it. [24]

It is this understanding of how people are shaped by the system that we aim to foster through disrupting the movement of people through space. In a city where flows are monitored and tracked, our spatial interventions create a moment for people to stop, redirect, and consider their built environment, particularly the seams and imperfections of space.

The objects themselves are influenced by the psychogeography movement. Psychogeography, the study of the “effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals,” [25] as well as other concepts (such as the Derive) created by the Situationist International, has informed our thinking about the alteration of movements through space. We believe that the seamless city will have negative effects on human emotions and behaviors, and that, by forcing urban dwellers to questions their hyper efficient routines, we can foster new interactions and create democratic moments.

The spatial interventions are a protest against the smoothness, the seamlessness and hyper-efficient aesthetic of the smart city. Drawing inspiration from the Japanese tradition of wabi-sabi, also known as the art of imperfection, which states that the beauty of objects lies in the imperfect, impermanent, and the incomplete, our objects consist of natural and scrap materials — interfaces that are unexpected in a hyper-efficient environment, and that celebrate seamfullness. The objects aim to surprise, excite and re-direct. The curved wooden wall diverts pedestrians from their path, while the ramp to nowhere forces people to turn around or decide to climb down. All objects also have a distinct materiality that creates an unexpected interface between the human and the built environment. The zen garden makes one slow down and inspect why the ground suddenly feels different and a bit unstable. The ramp, made of a soft foam that absorbs one’s steps, has a similar effect. The moss heap invites passers-by to linger and feel. By disrupting pedestrian’s efficient routes, we create moments that foster interaction and reflection and invite people to question their interfaces with each other and their environment.

The advantages of living in a city- proximity to infrastructure, resources and other people, are seemingly lost in its own hyper connectivity. These five spatial interventions are physical disruptions to the seamless and hyper-efficient urban flow. Not only do the interventions disrupt our shared data patterns, they also challenge our own data infused lives. By drawing on meaningful inefficiencies, psychogeography, and wabi-sabi, we hope to bring attention to the way data and invisible interfaces are seemingly defining our urban future and the individual’s experience of the city. It is in these spatial interventions and meaningful inefficiencies that we hope to prompt interfacing and interaction between city dwellers with each other and the built environment.

Conclusion

Shannon Mattern

In providing windows onto obfuscated urban processes and individuals’ everyday patterns of interacting with the city, in offering tools for epistemological experimentation, in furnishing methods for materializing and questioning various design ideals and social values, in orchestrating connections or tensions between alternative urban imaginaries, in translating between disparate urban subjectivities, and in cultivating spaces of productive friction and inefficiency, all of these aforementioned projects reveal the plurality of intelligences that makes up a vibrant city. Such a plurality cannot simply be aggregated into a collection of widgets on a universal urban dashboard. While urban and information commons are important spaces where urban publics can come together, we still need a variety of interfaces to mediate different urban intelligences and operations for different urban subjects. Public screens, apps, wearable technologies, analog gadgets, immersive fictions, social practices, responsive architectures, and street furnishings represent just a few of the many ways in which urban experience and epistemology can be given form.

And as many of these hypothetical and speculative projects show, the interface is not merely a product of the form-giving design process. Interfacing is also, ideally, a critical and iterative method within the design process itself. Translation, negotiation, mediation, operationalization – actions that define the interface – also propel design. The design process for our students involved countless negotiations between urban values – between automation and individual agency, security and freedom, efficiency and serendipity, profit and the public good, anthropocentrism and anti- or post-humanism, ‘smartness’ and wisdom. Then, when those designed artifacts encounter a public, either in the living city or in the pages of this publication, they have the potential to sustain those negotiations by prompting people to ask whether they want the urban imaginary these artifacts embody. Yet even outside this world of academic debate and speculation, where real urban interfaces are installed on our smartphones and performance dashboards and in our control rooms, we should hope that these artifacts promote prompt us to consider what urban values and visions they embody. And, more than that, they might also reveal their own methods and logics of operation, thereby demystifying the smartness that seeks to subsume the city’s epistemological abundance.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Provost’s Innovation in Education Fund at The New School for providing a generous grant to support our work in the Spring 2017 “Urban Intelligence” studio.

Author Biography

Urban Intelligence is Mariann Asayan, Fernando Berkovich, Burgess Brown, Melissa Dela Cruz, Lindsey Devers, Glenn Dungan, Diana Duque, Kate Fisher, Raha Ghassemi, Guillermo Gomez, Elena Habre, Alexander Jenseth, Yandong Li, Jeffrey Marino, Shannon Mattern, Joshua McWhirter, Francisco Miranda, Rami Saab, Shikha Singh, Leonore Snoek, Jack Wilkinson, and Irem Yildiz.

Notes and References

[1] CUSP, “NYU CUSP, Related Companies, and Oxford Properties Group Team Up to Create ‘First Quantified Community’ in the United States at Hudson Yards” (press release), April 14, 2014,http://cusp.nyu.edu/press-release/nyu-cusp-related-companies-oxford-properties-group-team-create-first-quantified-community-united-states-hudson-yards/.

[2] Orit Halpern, Jesse LeCavalier, Nerea Calvillo, and Wolfgang Pietsch, “Test-bed Urbanism,”Public Culture 25, no. 2 (2013): 273-306; Anthony Townsend, Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia (New York, NY: W.W. Norten, 2014); See also the series of articles on urban data and media infrastructures that Shannon Mattern has written for Places Journalsince 2013, https://placesjournal.org/author/shannon-mattern/.

[3] Martijn de Waal, The City as Interface: How New Media Are Changing the City (Rotterdam: nai010 Publishers, 2014); Rob Kitchin, “Rethinking, Reimagining and Remaking Smart Cities,” Programmable City Working Paper 20 (August 2016).

[4] Malcolm McCullough, Ambient Commons: Attention in the Age of Embodied Information (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013).

[5] Alexander R. Galloway, The Interface Effect (Malden, MA: Polity, 2012); Johanna Drucker, “Humanities Approaches to Interface Theory,” Culture Machine 12 (2011), https://www.culturemachine.net/index.php/cm/article/viewArticle/434.

[6] Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, Speculative Everything (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013).

[7] Lorraine Daston, Things That Talk: Objects Lessons in Art and Science (Brooklyn, NY: Zone Books, 2004); Sherry Turkle, Evocative Objects: Things We Think With (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007).

[8] Elliott Montgomery and Chris Woebken, Extrapolation Factory Operator’s Manual (Brooklyn, Extrapolation Factory, 2016).

[9] Thomas Nagel, “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” The Philosophical Review 83, no. 4 (October 1974): 435-450.

[10] One example of these researchers’ works includes Temple Grandin’s “squeeze machine,” a device that encapsulates the body in light pressure, a tactic that calms sensorially sensitive individuals. Grandin translated the concept from a phenomenon she observed in cows placed in squeeze chutes. See: Animals in Translation (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2005), 114-115.

[11] Thomas Thwaites, GoatMan, How I Took a Holiday from Being Human (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2016), 15.

[12] Ibid., 34.

[13] Murray Shanahan, “Conscious Exotica – Beyond Humans, What Other Kinds of Minds Might Be Out There?”Aeon, February 20, 2017, https://aeon.co/essays/beyond-humans-what-other-kinds-of-minds-might-be-out-there.

[14] Matthieu Ricard, A Plea for the Animals (Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications, 2016), 3.

[15] Robert Sullivan, Rats: Observations on the History & Habitat of the City’s Most Unwanted Inhabitants (New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2004).

[16] Lowell W. Adams, Urban Wildlife Habitats: A Landscape Perspective. Wildlife Habitats Version 3,(Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 57.

[17] Isobel Watts, Máté Nagy, Theresa Burt de Perera, and Dora Biro, “Misinformed Leaders Lose Influence Over Pigeon Flocks,” Biology Letters 12, no. 9 (September 2016).

[18] Albert Gidari, “‘Smart Cities’ Are Too Smart for Your Privacy,” Center for Internet and Society, February 20, 2017, http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/blog/2017/02/smart-cities-are-too-smart-your-privacy; Brian Nussbaum, “Smart Cities – The Cyber Security and Privacy Implications of Ubiquitous Urban Computing,” Center for Internet and Society, February 9, 2016, http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/blog/2016/02/smart-cities-%E2%80%93-cyber-security-and-privacy-implications-ubiquitous-urban-computing.

[19] Carlo Ratti, The City of Tomorrow: Sensors, Networks, Hackers, and the Future of Urban Life (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016).

[20] Liesbet Van Zoonen, “Privacy Concerns in Smart Cities,” Government Information Quarterly 33, no. 3 (2016): 472-80.

[21] Chantal Mouffe, The Democratic Paradox (New York, NY: Verso, 2000): 14, 15.

[22] Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York, NY: Vintage, 2016).

[23] Eric Gordon and Stephen Walter, “Meaningful Inefficiencies: Resisting the Logic of Technological Efficiency in the Design of Civic Systems,” in Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice, eds. Eric Gordon and Paul Mihaildis (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 243-266.

[24] ibid., 254.

Bibliography

Adams, Lowell W. Urban Wildlife Habitats: A Landscape Perspective. Wildlife Habitats Version 3, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1994.

CUSP. “NYU CUSP, Related Companies, and Oxford Properties Group Team Up to Create ‘First Quantified Community’ in the United States at Hudson Yards” (press release). April 14, 2014,http://cusp.nyu.edu/press-release/nyu-cusp-related-companies-oxford-properties-group-team-create-first-quantified-community-united-states-hudson-yards/.

Daston, Lorraine. Things That Talk: Objects Lessons in Art and Science. Brooklyn, NY: Zone Books, 2004.

Debord, Guy. “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography.” In Critical Geographies: A Collection of Readings, edited by Harald Bauder and Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro, 23-27. Kelowna, Canada: Praxis (e)Press, 2008.

De Waal, Martijn. The City as Interface: How New Media Are Changing the City. Rotterdam: nai010 Publishers, 2014.

Drucker, Johanna. “Humanities Approaches to Interface Theory.” Culture Machine 12 (2011), https://www.culturemachine.net/index.php/cm/article/viewArticle/434.

Dunne, Anthony, and Fiona Raby. Speculative Everything. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013.

Galloway, Alexander R. The Interface Effect. Malden, MA: Polity, 2012.

Gidari, Albert. “‘Smart Cities’ Are Too Smart for Your Privacy.” Center for Internet and Society, February 20, 2017. http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/blog/2017/02/smart-cities-are-too-smart-your-privacy.

Gordon, Eric, and Stephen Walter. “Meaningful Inefficiencies: Resisting the Logic of Technological Efficiency in the Design of Civic Systems.” In Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice, edited by Eric Gordon and Paul Mihaildis, 243-266. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016.

Grandin, Temple. Animals in Translation.New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2005.

Halpern, Orit, Jesse LeCavalier, Nerea Calvillo, and Wolfgang Pietsch. “Test-bed Urbanism.” Public Culture 25, no. 2 (2013): 273-306.

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York, NY: Vintage, 2016.

Kitchin, Rob. “Rethinking, Reimagining and Remaking Smart Cities.” Programmable City Working Paper 20 (August 2016).

McCullough, Malcolm. Ambient Commons: Attention in the Age of Embodied Information. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013.

Montgomery, Elliott, and Chris Woebken. Extrapolation Factory Operator’s Manual. Brooklyn, Extrapolation Factory, 2016.

Mouffe, Chantal. The Democratic Paradox. New York, NY: Verso, 2000.

Nagel, Thomas. “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” The Philosophical Review 83, no. 4 (October 1974): 435-450.

Nussbaum, Brian. “Smart Cities – The Cyber Security and Privacy Implications of Ubiquitous Urban Computing.” Center for Internet and Society, February 9, 2016. http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/blog/2016/02/smart-cities-%E2%80%93-cyber-security-and-privacy-implications-ubiquitous-urban-computing.

Ratti, Carlo. The City of Tomorrow: Sensors, Networks, Hackers, and the Future of Urban Life. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016.

Ricard, Matthieu. A Plea for the Animals. Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications, 2016.

Sullivan, Robert. Rats: Observations on the History & Habitat of the City’s Most Unwanted Inhabitants. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2004.

Shanahan, Murray. “Conscious Exotica – Beyond Humans, What Other Kinds of Minds Might Be Out There?”Aeon, Feb. 20, 2017. https://aeon.co/essays/beyond-humans-what-other-kinds-of-minds-might-be-out-there.

Thwaites, Thomas. GoatMan, How I Took a Holiday from Being Human. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2016.

Townsend, Anthony. Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia. New York, NY: W.W. Norten, 2014.

Turkle, Sherry. Evocative Objects: Things We Think With. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

Van Zoonen, Liesbet. “Privacy Concerns in Smart Cities.” Government Information Quarterly 33, no. 3 (2016): 472-480.

Watts, Isobel, Máté Nagy, Theresa Burt de Perera, and Dora Biro. “Misinformed Leaders Lose Influence Over Pigeon Flocks.” Biology Letters 12, no. 9 (September 2016).