James Bulley

PhD Student, Department of Music, Goldsmiths, University of London

Email: j.bulley@gold.ac.uk

Web: http://www.jamesbulley.com

Astra Price

Faculty, Program in Film and Video, California Institute of the Arts

Archivist, Bill Viola Studio

Email: aprice@calarts.edu

Reference this essay: Bulley, James, and Astra Price. “The Talking Drum.” In Sound Curating, eds. Lanfranco Aceti, James Bulley, John Drever, and Ozden Sahin. Cambridge, MA: LEA / MIT Press, 2018.

Published Online: December 15, 2018

Published in Print: To Be Announced

ISBN: 978-1-912685-55-4 (Print) 978-1-912685-56-1 (Electronic)

ISSN: 1071-4391

Repository: To Be Announced

Abstract

The following paper reflects upon the authors’ experiences of assisting in the realization of the spatial sound work The Talking Drum by Bill Viola. Originally recorded as an exploratory performance between 1979–82, The Talking Drum was realized as an immersive sound installation at the Vinyl Factory Space, Brewer Street, London, from 13 October to 7 November 2015. [1]

The paper is a collaborative endeavor, between Astra Price (California Institute of the Arts and archivist at Bill Viola Studio) and James Bulley (artist and researcher at Goldsmiths, University of London) who worked together with Viola and his partner Kira Perov in Summer 2015 to transform archival recordings of the originally site-specific performance recording into a spatialized sound installation. Here we seek to explore the contextual, theoretical and curatorial discourse that arose in the re-presentation of the work.

Keywords:

sound, spatial, installation, curation, bill viola, talking drum

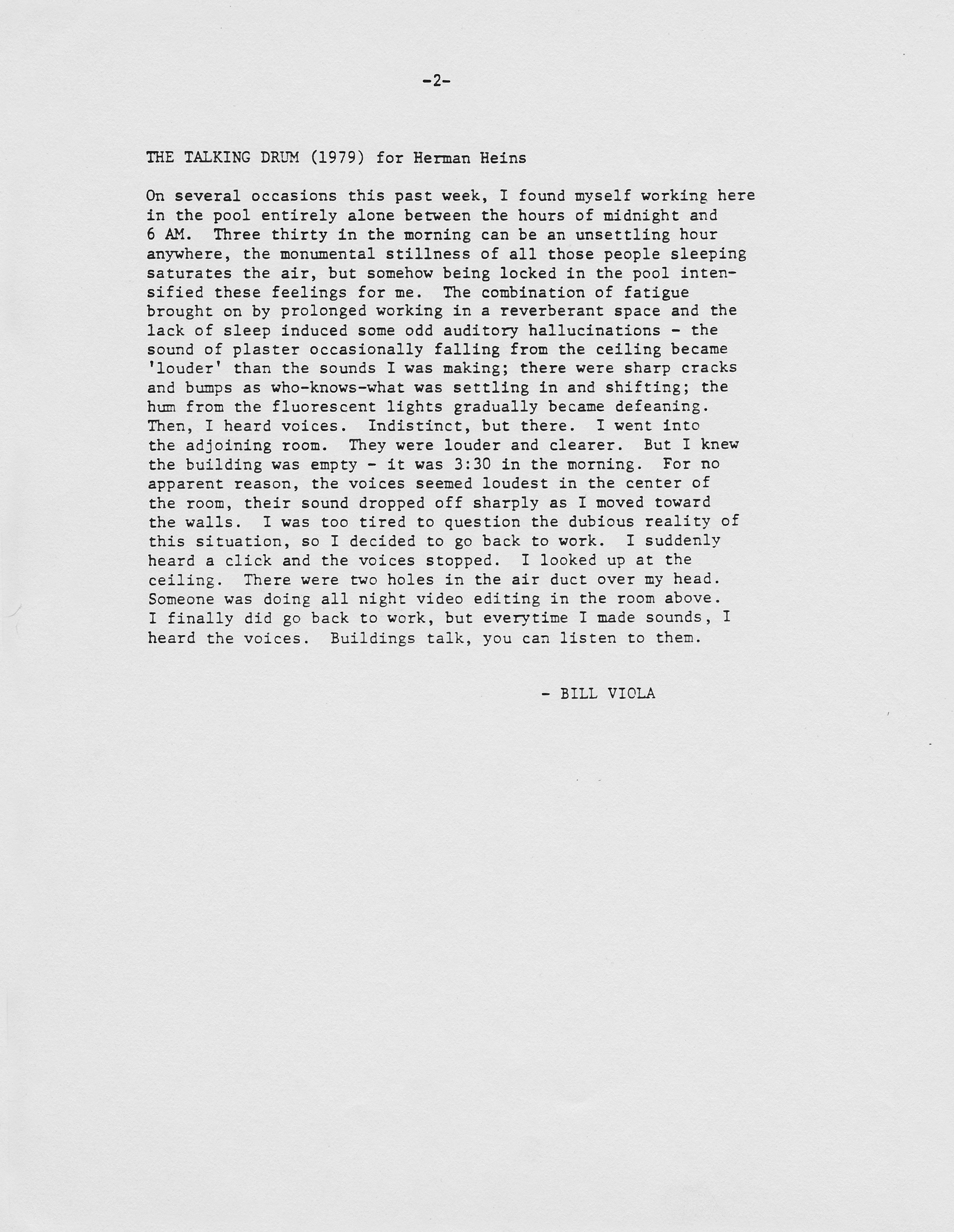

“Buildings talk, you can listen to them.” [2]

Bill Viola, 1979.

Introduction

When reflecting on re-presentation, those of us working in archives often find ourselves questioning the boundaries of fiction and non-fiction, of reality and non-reality. These dimensions, usually separated from our common experience of life, can merge in space and time, conjuring the past in the present: creating vibrancy between that which is documented and the here and now. By witnessing we create trace — whether material or memorial — and from this follows inscription. [3] From the dust surrounding the document, histories can unfold, altering the status of the original document and revealing new opportunities for re-presentation.

Origins

Sitting in a corner of Viola’s studio just outside Long Beach, California is a full drum kit, a thin layering of dust covering its skin. The last time it sounded is hard to determine; most likely several years ago. For now, it sits in resonant expectation of its cavernous industrial production warehouse. With the work of Bill Viola, patience and anticipation are essential elements.

Throughout his career, Bill Viola has expounded time as his material, [4] a flexible notion [5] that folds upon itself in the landscape of his work. Though known in most contemporary art circles as a video artist, one of Viola’s earliest creative endeavors was as a drummer, an experience he cites as a strong influence on his subsequent artistic development. [6] Viola began studying at Syracuse University in 1969, taking classes in electronic music. [7] In 1972 Viola met the composers Alvin Lucier and Robert Ashley, [8] and in Summer 1973 he came into contact with the composers David Behrman, Gordon Mumma and David Tudor at an experimental music workshop in New Hampshire. From these experiences, Viola’s formative technical and inclusive understanding of the electronic arts grew – he later commented “the electronic signal was a material that could be worked with” [9] and “when electronic energies finally became concrete for me, like sounds are to a composer, I really began to learn.” [10] For Viola, it was not the medium in its physical sense that was important, but the spatial and time-based properties that electronic signals could afford as material for creating experience.

Viola completed his BFA in Experimental Studios in 1973, just as upstate New York became a hotspot for artists relocating due to the availability of academic jobs and grants unavailable to those in New York City. [11] In 1973 Viola had become one of the founding members of the Composers Inside Electronics (CIE) group, alongside John Driscoll, Linda Fisher and Phil Edelstein. The group worked together to realize and perform both their own works and collaborations, including Rainforest IV with David Tudor, [12] an experience that Viola later described as “probably the greatest experience I had in terms of opening up my eyes and ears to the invisible world of sound.” [13] Within Rainforest IV, the audience experienced a landscape of hand made audio devices and found objects suspended in space, their material resonances activated by transducers driving prerecorded found sounds through them. In performing Rainforest IV, a work produced in the same year that Lucy Lippard’s Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966-1972 was published, Viola experienced a work that challenged material presentation by resonating the space and bodies of its audience.

Excerpt from Rainforest IV from Leonardo Electronic Almanac on Vimeo.

David Tudor, Rainforest IV performance (BVS16183), 1974. Excerpt. Courtesy Bill Viola Studio and Composers Inside Electronics.

The late 1960s and early 1970s in the United States saw rapid change in the tenets of artistic practice. Site-specific activities [14] propagated calls for bodily presence in real time and space, [15] an attention to being there, [16] what Alan Badiou termed “the passion for the real” [17] – an opposition to one-dimensional mediated consumerism. [18] Viola’s involvement in Rainforest IV had a strong influence on his thinking, leading him to adopt an inclusive notion of field perception [19] in his work. Field perception focuses upon multi-sensoriality, a consideration that all senses exist simultaneously – a synaesthetic-like attentiveness [20] that Viola feels more accurately reflected human experience.

In the 1970s, Viola travelled extensively, staying in Europe for an extended period, where he worked as the technical director of the art/tapes/22 video studio in Florence, Italy. Whilst in Florence, Viola explored the acoustics of its pre-Renaissance cathedrals, noting that there is “a kind of acoustic architecture in any given space where sound is present, and that there is a sound content, an essential single note or resonance frequency latent in all spaces, I felt I had recognized a vital link between the unseen and the seen, between an abstract, inner phenomenon and the outer material world.” [21] At this time Viola evolved a concept that has become a core aspect of his practice — the manipulation of physical presence in time. This is perhaps most succinctly encapsulated in He Weeps for You (1976), an installation within which a tiny drop of water slowly emerges from the end of a narrow pipe in front of a live camera: “The drop grows in size gradually, swelling in surface tension, until it fills the screen. Suddenly it falls out of the picture and a loud resonant “boom” is heard as it lands on an amplified drum. Then in an endless cycle of repetition, a new drop begins to emerge and again fill the screen.” [22] In He Weeps for You, Viola composed what he terms a “tuned space” [23] – an ecology of elements functioning together to create the work as a whole.

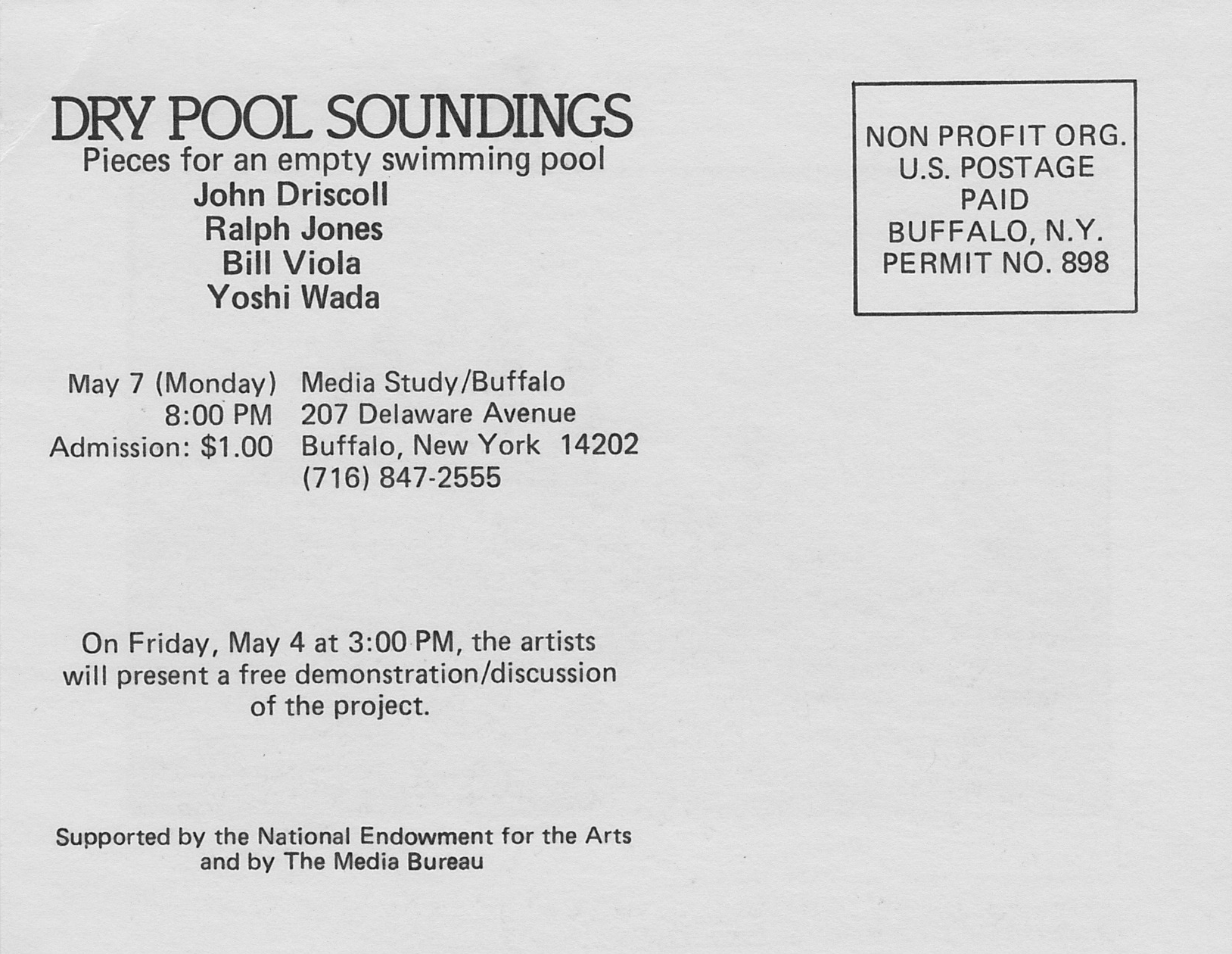

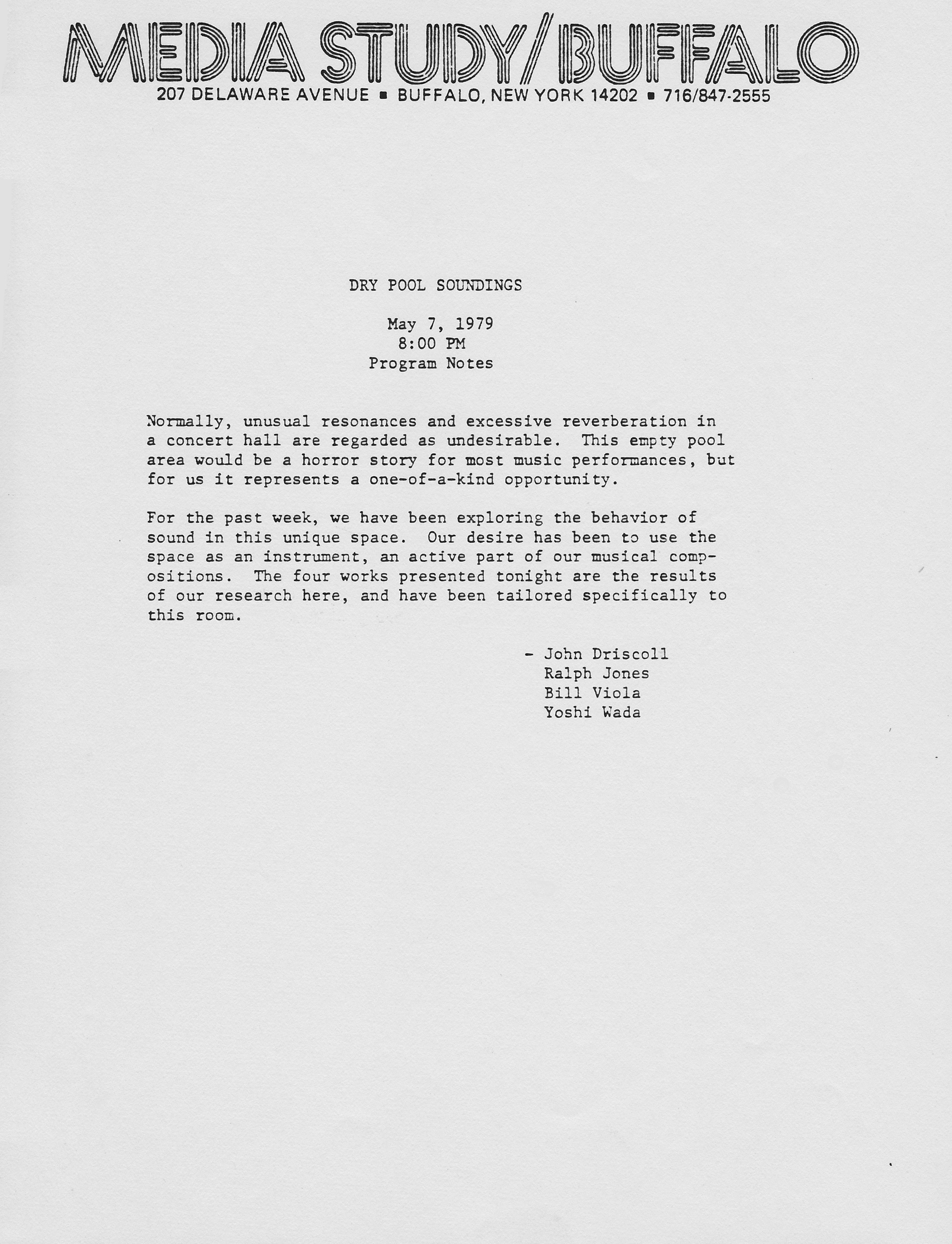

In Spring 1979, Viola, alongside CIE members John Driscoll, Ralph Jones, and sculptor/musician Yoshi Wada, took part in a self-initiated performative residency entitled Dry Pool Soundings at the empty swimming pool at SUNY/Buffalo, New York. Viola’s performance within the residency, The Talking Drum (1979) (For Herman Heins), was a part improvised performance work for solo bass drum that explored the large resonant space through rhythmic patterning and gated playback of field recordings triggered by percussive hits during portions of the performance. The recorded material Viola created in this residency, along with an additional re-recording session with the assistance of Bob Bielecki in 1982 at the same location, makes up the entirety of the source material for the installation of The Talking Drum that was presented in the Brewer Street car park in 2015.

The Talking Drum

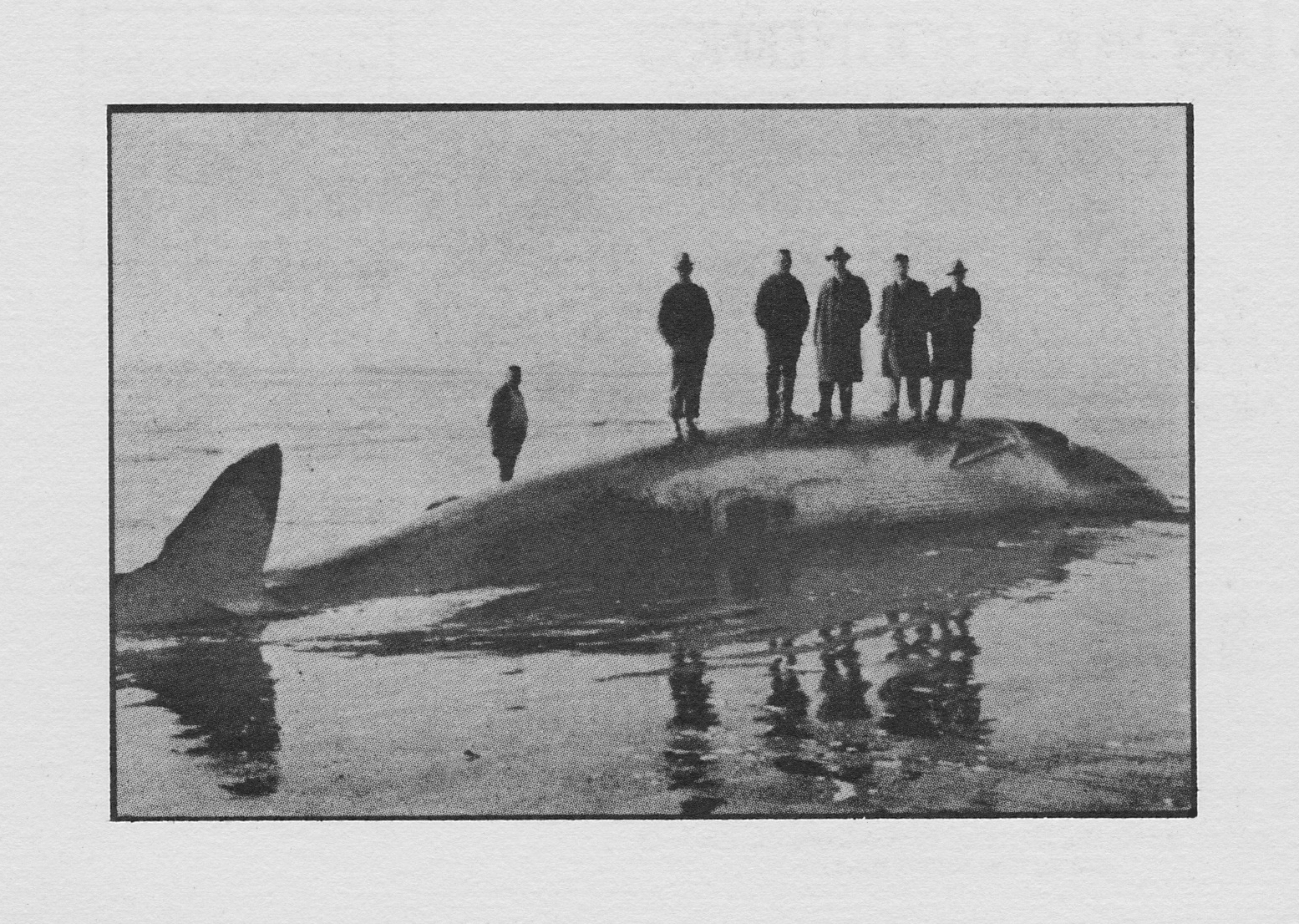

Throughout his career, Bill Viola has been drawn to represent human experience through symbolism and spiritualism. [24] The two entwine within The Talking Drum, a work whose title and form evoke the talking drums of Central and Western Africa, used to convey messages between remote tribes people. The Welsh explorer H. M. Stanley, journeying in the Congo from 1875 to 1877, observed: “The islanders have not yet adopted electric signals but possess, however, a system of communication quite as effective. Their huge drums by being struck in different parts convey language as clear to the initiated as vocal speech…” [25] In his 1949 study, Talking Drums of Africa, J.F. Carrington heard communications that were built upon mimicry of the melodic and rhythmic characteristics of local languages: each signal was unique to the specific region, a locative expression of those people [26] and that landscape. Carrington learnt that the drummers paid close attention to the temporal and topographical conditions for drumming, favoring early morning or late evening with proximity to water. [27] This timing meant a lessening of human peripheral noise, and the location propagated the sound great distances over the reflective surface of the water. A single talking drum message could last twenty minutes or more, signed off with a tattoo of sparse low frequency drum hits. [28]

In the performing of The Talking Drum, Viola resonated the geographically distant and obvious past of communication in Central and Western Africa. The low beating of a bass drum is a historic acoustic symbol, a staple of human communicative expression, a means to signify presence and existence; to represent the unseen Gods (as in Greek drama), the sublimity of nature (the storm), or to induce human sensitivity to situation [29] (in modern feature film). It is a sound bound with a universally understood code of meaning; heard throughout human existence, symbolic of the heartbeat, the singular expression of our natural rhythm – its presence signals a message from the one to the many. Talking drum messages can be heard as both a sound signal (for attentive listening) and as what R. Murray Schafer has called a soundmark [30] (a unique communal sound).

The titling of The Talking Drum is not however a purely symbolic exercise: the instrumental attributes of the large drum allowed Viola to interrogate the acoustics of the swimming pool at SUNY/Buffalo, illuminating the space through what Barry Blesser has termed aural architecture. [31] The performative system that Viola constructed resonated the tambura [32] of the swimming pool, causing an unactivated field of overtones and resonances to be drawn out by the beat of the drum. The effect recalls Viola’s experiences in the cathedrals of Florence, within which he heard sounds that were “detached from the immediate scene, floating somewhere where the point of view has become the entire space.” [33]

The drum and the heartbeat are motifs that recur in Viola’s work, [34] conveying his understanding of the heart as the image of the rhythm of life: “the basic pattern of crescendo – peak – decrescendo is the basic rhythmic structure of life itself, and reflexively of many of our activities within it.” [35] This dynamic and structuring principle is heard within The Talking Drum recordings: the audience are both witness to Viola’s original presence within the empty swimming pool at SUNY/Buffalo, and immersed in a singular rhythmic mortality. For Viola his use of recurring motifs (both sonic and visual) allows transferral of meaning through the ecologies of his work – combined, the motifs represent a sign system, [36] forming songlines [37] that map invisible internal pathways across the landscape of Viola’s work.

The use of gate triggered field recordings within The Talking Drum performance at SUNY/Buffalo adds a further level of acoustic communication within the dry pool. As the frequency range of the drum hit is in the low end of the audible spectrum, the hits do not entirely mask the field-recorded sounds, most of which are located at the high end of the frequency spectrum. The field recordings are partially masked by the intensity of each drum hit, and become increasingly audible immediately after the attack. The result is what Viola refers to as afterimages, [38] ghost-like sounds audible only through attentive listening to the architecture of the space.

From the Archive

Investigating The Talking Drum for re-presentation in 2015 posed two equally important questions: what material from the original performances still existed, and how would the work change in re-presentation.

Much like Viola’s drum set, the boxes that contained the ¼“ audio tape recordings of the original performances of The Talking Drum were layered in dust. Whilst most of Viola’s early video works have had a consistent level of attention, preservation and upgrading to contemporary media, many of the open reel ¼“ audio tapes have not. There were multiple full recordings of the piece from different performances of works in 1979 and 1982, and all of the tapes were in surprisingly good condition. Having gathered the material related to The Talking Drum, the tapes were taken to Audio Mechanics in Burbank, California where high quality digital transfers were made. Price then undertook detailed listening sessions with the material, analyzing the recordings and writings on each tape box.

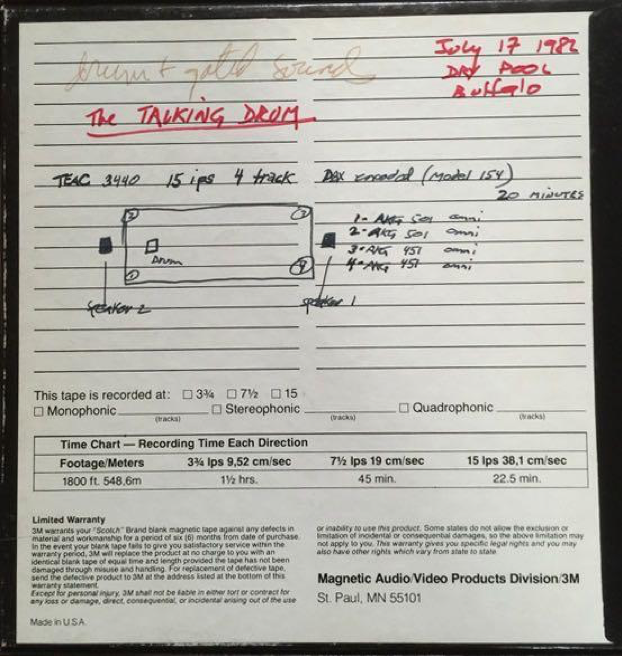

Price’s findings were more complex than expected: although The Talking Drum was originally presented to an audience at the end of the Dry Pool Sounding residency in 1979 as a live explorative performance, Viola returned to the work in 1982, re-staging the performance to record aspects of the acoustic space that he felt had not been adequately represented in 1979. In 1979 and 1982 Viola had not chosen a singularly representative recording of the work. The recording that Viola and Perov (who was present for the 1982 performance) felt best represented the essence of the work was from the 1982 re-recording session. It had been recorded onto a four-track TEAC A-3440 deck, with one mono microphone for each track (two omni AKG 501s and two omni AKG 451s). On the back of the tape box was a diagram clearly portraying the microphone and speaker layout used. Centered, at either end of the pool, on the deck, were two speakers (playing back the gated field recordings), and at each corner of the pool deck was a microphone. Viola, performing, was seated toward one side in the basin of the dry pool. A microphone on the bass drum fed an electronic system in which the attack of the drum instantaneously triggered a gate to release prerecorded sounds “such as dogs barking, people yelling, birds screeching, and machinery operating” [39] to the speakers at the level of the pool deck.

The original recordings of The Talking Drum have highly site-specific characteristics “derived from the physical place of performance – the empty swimming pool.” [40] Viola’s original performances investigated spaciousness: [41] the acoustic space served to increase the apparent source width of the drum and envelop the listener in reverberance. In his description of the work in the Whitney catalog of 1997, Viola noted that the pool had “an acoustic reverberation of over nine seconds” [42] and the “resonant characteristics of the architecture in turn affect the introduced sounds, altering their original qualities and sonic form.” [43] In recording the performance, Viola acted as aural architect, sounding out the dry swimming pool, inscribing its topography and rendering its material trace on ¼“ audio tape. From the listening sessions, it was obvious that any re-presentation of the work would have to clearly acknowledge the performer and space within the recording, integrating it within the acoustics of Brewer Street car park.

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, the function of the archive within artistic discourse became unstable, with its former status as static, frozen in time, a concrete and unchangeable repository of documents [44] questioned and irrevocably disrupted. [45] The archive is instilled with a sense of ever becoming, its corpus acting as a dynamic and generative medium used to procreate and recreate the items contained within. This ontological shift has in part been caused by shifting relationships between artwork and documentation; history and theory are now considered neither completely outside the realm of art nor completely within it. When presenting work from the archive, history and theory function as dynamic rather than static media [46] – the materials of the archive are activated by the passing of time. In the investigation of items in a state of temporal remission [47] they become active, changed, unstable.

As the primary person in charge of cataloging and analyzing the materials, Price allowed her previous work with Viola to guide her understanding of the options for re-presentation. Viola’s core concept of the manipulation of the physical presence in time had to be of primary focus. The decision was made to present the work not as documentary artefact, but as a transient site-specific work whose aura bore both the original inscription and the newfound site-specific context.

Site

In contemporary practice, a shift has taken place in the rehabilitation of site-specific art. Whilst embodying the anti-commercial and call-for-presence attitudes of the 1960s, site-specific work has been affected by institutionalization, globalization and commercialization, moving away from a singular, fixed, grounded phenomenon exemplified in the sculptures of Richard Serra. In recent years critics have declared the notion of place in crisis, lost in the contemporary, detrimental to a subject’s capacity to have a coherent sense of self and grounded identity in the world. In modern deterritorialized life, the sense of place is unbound from the physical actuality of a geographic location, producing a freeing effect — a fluid migratory model, conveyed in Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizomatic nomadism. [48] Site-specificity in the contemporary embraces an itinerant, transient experience, informed by hybrid digital electronic spaces, [49] reactive to dynamics of deterritorialization. This cross-media itinerant interrogation of space and place is embodied in the audio and video practice of the artists Janet Cardiff and Christina Kubisch. [50]

In re-presenting The Talking Drum, both locational and itinerant constructs of site-specificity are at play. The original site (the dry pool) is what James Meyer has called the literal site: [51] the singular place, in situ, the place that determines the outcome of the work. In the re-presentation of The Talking Drum, the site is no longer literal, becoming what Meyer terms a functional site: [52] “not a map but an itinerary, a fragmentary sequence of events and actions through spaces, that is, a nomadic narrative whose past is articulated by the passage of the artist.” [53] The site thus becomes a function that occurs between two locations (the original and the new), a temporal interrogation between document and place.

When re-siting a site-specific work, it is vital to reflect upon the relationship between the new instance of the work and those instances that have come before. When the artist Faith Wilding re-sited her 1972 work Crocheted Environment [54] at the Bronx Museum in 1995, aiming to ensure its preservation and status within the canon of feminist art, its relocation away from the context it was created for greatly reduced its relevance and impact, despite the presence of the artist to oversee the new instance. [55] For Viola, who with Perov oversaw every aspect in the realization of The Talking Drum, the challenge of re-presenting work is a common one; his combinatory use of archetypes drawn from his travels across the world imbue his works not only with multi-sensoriality, spirituality and symbolism, but with an intrinsic sense of place out of time.

Brewer Street

After determining the archival materials for re-presentation, Viola, Perov and Price began to explore the integration of the 4-track recording within the architecture of Brewer Street car park. After exploring a stereo re-mapping based on the frequency space of the original recordings, it was decided to focus the realization on Viola’s spatial experience as the performer within the basin of the pool, utilizing a sub cabinet as both aurally and physically representative of the original bass drum, and four speakers to mark the acoustic arena of the pool. As Barbara London has noted, Viola’s artistic intention is “to move the viewer on a very direct level, to the point that he or she will relive his experience” [56] and by working with this spatial precept, the listener could be present as both audience in Brewer Street car park and artist in the midst of performing The Talking Drum in the dry pool in 1982.

A first version of this 4.1 channel mix was then sent over to Bulley in London, who arranged for a test installation at the car park to ascertain the cohesiveness of the mix in the space. After a series of listening sessions on the floor of the car park with engineer Tom Richards, it was decided to embrace the reflective properties of the car park space by mounting four Meyer UPA 1P speakers in a rectangular array on the ceiling of the car park. The physical and acoustic profiles of the sub-woofer-as-drum were augmented using an additional Meyer USW-1P sub cabinet. Carpeting the floor was considered but discarded due to its sterilizing aesthetic impact, and to promote the combining of the two acoustic spaces. The resonant frequencies within the space were identified whilst mixing, with the array and mix calibrated to both take advantage of and not be overwhelmed by them. It became clear that the piece should balance at a midpoint between the architectural acoustics of both the car park and the dry pool in the recordings. Field recordings of the resultant mixes were then sent back to Viola, Perov and Price for consideration. As the work would function as a long durational installation, with The Talking Drum alternated with Viola’s work Hornpipes, and listeners would be free to explore the space in their own time, the mixing process necessarily involved Viola, Perov, Price and sound engineer Jon Polito working with the understanding of the Brewer Street space in the studio, walking around to hear how the experience changed as they stopped, listened and moved through different zones.

A few days before the opening of the work, Viola and Perov travelled to London, visiting the car park for a series of detailed listening sessions and discussions within which final mix parameters were set. It was decided to stage the work in near darkness, with discreet up lighting designed to highlight the architecture of the space. The night-like attributes of this design encouraged careful, active exploration: a recognition of the human need for what Viola has referred to as “concealed places – some element of mystery, a dark room in which to really be who we are. We don’t want to illuminate every corner.” [57]

Artist-Curator

At Brewer Street, Viola and Perov acted as film or theatre directors might, working collaboratively and meticulously to achieve the instantiation of the work in the space. In Viola’s work framing conventions are made explicit: the tuned spaces are ecologies of systematic meaning, rendered across media, space and place to create experience located in time. In re-presenting The Talking Drum in the acoustic space of Brewer Street car park, Viola necessarily acted as artist-curator (and one might add to that acoustician), creating an aural architecture that aligned the acoustic horizon of SUNY/Buffalo dry pool with the cavernous basement of Brewer Street car park, himself a resonance manipulated through time.

Conclusion

The relationship of an artist to their living archive is inherently complex and incomplete. The artist’s archive is delineated by curatorial strategies and innate material instability. To ensure accessibility and preservation in a digital age, translation must occur, often multiple times in a document’s lifecycle. These changes can range from the perceptibly unnoticeable to a complete re-conception. For the site-specific artist involved in documenting their work, the problems of re-presentation are only heightened: the artist must be conditioned and comfortable with their work as an evolving space. The work becomes an open system that exists in a deterritorialized and networked environment. Contemporary site-specific practice challenges our conception of place as both locational and temporal, and interrogates the fixed nature of the archival object. The re-presentation of The Talking Drum detailed in this paper created an immersive auditory experience that, whilst markedly different from the original performance, conveyed the heart of the work for all that participated in the process. For Viola, an artist whose career has spanned over 40 years, the piece is part of a wide body of work that has continually evolved mediated, spatial experiences for his audiences.

The reconsideration of site in the Brewer Street installation of The Talking Drum proved both practically complex and metaphorically simple. The aural architecture that Viola created in both the 1979 and the 1982 performances of the work was embedded within the recording; it had to be recognized, acknowledged and harmoniously incorporated into the new location whilst ensuring that the alternate site for Viola’ work, the internal experience of the audience and performer, was still present. The iteration of The Talking Drum at Brewer Street shows that curation is intrinsic to Viola’s practice; in his creation of spaces that act as platforms for audience experience, every aspect of the framing, staging and materialization is considered. For an artist creating/curating spatial sound works, the role of artist-curator is vital; the acoustic architecture of the site defines the experience of the work. The work cannot exist without the space, and the physical attributes of the space shape and define the experience of the sound for the listener. For Viola, the work is tuned to the space, allowing for a field of perception within which the audience gains their experience.

In listening to The Talking Drum at Brewer Street visitors were enveloped in the latent rhythms of its patterning, resonating and reverberating in the spaciousness of the car park. Over long periods, differences amongst the sounds would disappear, masked by a feeling of incessant transition, of multiplicity, what Henri Bergson has referred to as “succession with separation,” [58] the unending Om from which everything proceeds.

Acknowledgments

Our most sincere thanks go to everyone at Bill Viola Studio (Bobby Jablonski, Kira Perov, Bill Viola, Gene Zazzaro et al.) for their tireless work on the exhibition, their continued assistance during the writing of this article, their high tolerance for endless questions and kind permission for the use of the photographs and video included within. Thank you also to John Driscoll who generously allowed us to use archival materials from Rainforest IV that have not been publicly seen before. In London, thank you to all at The Vinyl Factory (in particular Joana Seguro and Tom Richards) and to Blain|Southern, particularly Jess Fletcher, Deklan Kilfeather and Graham Southern, all of whom were instrumental in the re-presentation of The Talking Drum.

Notes and References

[1] In addition to its re-presentation as a site-specific installation at The Vinyl Factory Space at Brewer Street Car Park from13 October to 7 November 2015, a remastered stereo version of the work was issued as a limited edition record pressed by The Vinyl Factory, in collaboration with Blain|Southern and Bill Viola Studio.

[2] John Driscoll, Ralph Jones, Bill Viola, and Yoshi Wada, Dry Pool Sounding Program Notes (Buffalo, May 7, 1979), 1.

[3] “[T]o say witness is to say trace, and to say trace is to say inscription.”

Jean-Francois Lyotard, Domus and the Megapolis, in The Inhuman Reflections on Time, trans. Geoff Bennington and Rachel Bowlby (Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press, [1993],1998), 197-8.

[4] Time is the water we exist in like fish. You might say it’s oxygen, but I think time really is our element.” – Bill Viola interviewed by William Furlong, Venice, 1995.

William Furlong, “Bill Viola,” Speaking of Art: Four Decades of Art in Conversation, with an introduction by Mel Gooding (London: Phaidon Press, 2009), 156.

[5] “Bill Viola is always seeking to show that time is a flexible notion, with present and past growing part or becoming mutually integrated through the use of technologies.”

Maria Rosa Sossai, “Reflections Beyond the Threshold of the Visible,” in Bill Viola: Reflections, ed. Anna Bernardini (Cinisello Balsamo, Milano: Silvana, 2012), 27.

[6] “I started playing drums in a rock and roll band when I was in high school, and continued into my university days. That was the real focus of my life. It was the first time I really had the experience of practicing and developing something, perfecting a skill-of pushing it beyond an initial stage. This has always stayed with me and helped me develop my video work.”

Raymond Bellour and Bill Viola, “An Interview with Bill Viola,” October 34 (1985): 91.

[7] “Yes, in the university I also took classes in electronic music. We had one of the first of the early music synthesizers, the Moog; working with it was like doing sculpture. I had always liked tape recorders, microphones, and so on, and this took me even further into electronics and technical things.”

Raymond Bellour and Bill Viola, “An Interview with Bill Viola,” October 34 (1985): 91.

[8] “Viola met “new music” composers Alvin Lucier and Robert Ashley at Syracuse in 1972, and during the summer of 1973 he came into contact with composers David Tudor, Gordon Mumma, and David Behrman at an experimental music workshop in Chocorua, New Hampshire.”

Barbara London, “Bill Viola: the Poetics of Light and Time,” in Bill Viola : Installations and Videotapes, ed. Barbara London (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1987), 11.

[9] Bill Viola quoted in Raymond Bellour and Bill Viola, “An Interview with Bill Viola,” October 34 (1985): 93.

[10] Bill Viola quoted in Raymond Bellour and Bill Viola, “An Interview with Bill Viola,” October 34 (1985): 93.

[11] Chris Hill, “Interview with Steina Vasulka,” Experimental Television Center, 1995, http://www.experimentaltvcenter.org/interview-steina-vasulka (accessed July 2016).

[12] See Viola’s article on David Tudor: Bill Viola, “David Tudor: The Delicate Art of Falling,” Leonardo Music Journal 14 (2004): 48–56. DOI:10.2307/1513505.

[13] Bill Viola quoted in John G. Hanhardt, Bill Viola, edited by Kira Perov (London: Thames & Hudson, 2015), 13–14.

[14] “A new kind of post formalist aesthetic emerged in which art now looked to systems theories, linguistics, site specificity, and art’s environmental dimension, rather than the traditional aesthetic form.”

Paul O’Neill, The Culture of Curating and the Curating of Culture(s) (Cambridge, MA; London, England: The MIT Press, 2012), 21.

[15] “An antidote to McLuhanism, to popular culture’s virtual pleasures and blind consumerism, the aesthetics of Presence imposed rigorous, even puritanical demand: attendance at a particular site or performance; an extended, often excruciating duration.’ Thus the notion of site specificity allied a New Left critique of the “System” with a phenomenology of Presence, a spectatorship that unfolded in “real time and space.”’

James Meyer, “The Functional Site; or, the Transformation of Site Specificity,” in Space, Site, Intervention, ed. Erika Suderburg (Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 26.

[16] “Thus the premise of site-specificity to locate the work in a single place, and only there, bespoke the 1960s call for Presence, the demand for the experience of “being there”. An underlying typos of Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology, of the happening and performance, Presence became an aesthetic and ethical cry de coeur among the generation of artists and critics who emerged in the 1960s, suggesting an experience of actualises and authenticity that would contravene the depredations of an increasingly mediated, “one-dimensional” society.”

James Meyer, “The Functional Site; or, the Transformation of Site Specificity,” in Space, Site, Intervention, ed. Erika Suderburg (Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 26.

[17] See: Alain Badiou, The Century, translated by Alberto Toscano (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007).

[18] “The idealism of modern art, in which the art object in and of itself was seen to have a fixed and transhistorical meaning, determined the object’s placelessness, its belonging to no particular place, a no-place that was in reality the museum – the actual museum and the museum as a representation of the institutional system of circulation that also comprises the artist’s studio, the commercial gallery, the collector’s home… Site-specificity opposed that idealism – and unveiled the material system it obscured – by its refusal of circulatory mobility, its belongingness to a specific site.”

Douglas Crimp and Louise Lawler, On the Museum’s Ruins (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1995), 17.

[19] “In 1973 I met the musician David Tudor and became part of his Rainforest project, which was performed in many concerts and installations throughout the seventies. One of the many things I learned from him was the understanding of sound as a material thing, an entity. My ideas about the visual have been affected by this, in terms of something I call “field perception,” as opposed to our more common mode of object perception. [..] I do not consider sound as separate from image. We usually think of the camera as an “eye” and the microphone as an “ear,” but all senses exist simultaneously in our bodies, interwoven into one system that includes sensory data, neural processing, memory, imagination, and all the mental events of the moment. This all adds up to create the larger phenomenon we call experience.”

Bill Viola, Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1995), 151–2.

[20] “Synaesthesia is the natural inclination of the structure of contemporary media. The material that produces music from a stereo sound system, transmits the voice over the telephone and materialises the image on a television set is, at the base level, the same.”

Bill Viola, Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1995), 165.

[21] “Bill Viola, in response to Questions from Jorg Zutter,” first published in Bill Viola: Unseen Images, ed. Marie Luise Syring (Dusseldorf: Verlag R. Meyer, 1992), 93-111 (German, English, French) in Bill Viola, Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1995), 241.

[22] Bill Viola, “He Weeps for You (1976), catalogue notes,” in Bill Viola: Installations and Videotapes (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1987), 29.

[23] “The ensemble of elements in this installation evokes a “tuned space,” where not only is everything locked into single rhythmical cadence, but a dynamic interactive system is created where all elements (the water drop, the video image, the sound, the viewer, and the room) function together in a reflexive and unified way as a larger instrument.”

Bill Viola, “He Weeps for You (1976), catalogue notes,” in Bill Viola: Installations and Videotapes (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1987), 30.

[24] “Viola has long been absorbed with how, during the eighteenth century, Blake was constructing a symbolic model of the universe that was freed from empirical observation. He has been particularly drawn to Blake’s method of representing the world through symbols, ideas and spiritual phenomena.”

Barbara London, “Bill Viola: the Poetics of Light and Time,” in Bill Viola: Installations and Videotapes (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1987), 14.

[25] Henry Morton Stanley, The Founding of the Congo Free State (London: Sampson Low, 1885) in J. F. Carrington, Talking Drums of Africa (New York, NY: Negro Universities Press, 1969), 7.

[26] “For the language used on the drum is the local language of the small tribal group. Even where a trade language such as Ngala is known and used, the members of the tribal group will still use their own tongue for intercommunication; this tribal language is still the language learned by a child at its mother’s knee and it forms the basis of the drum language.”

- F. Carrington, Talking Drums of Africa (New York, NY: Negro Universities Press, 1969), 13.

[27] “Times of beating; distance of travel. The best conditions for drum beating usually obtain in the early morning or late evening. There are two main reasons for this. During the day the many noises of the village and occupations of the people prevent messages from being audible except for short distances. And secondly, the heating effect of the sun’s rays striking the ground causes air movements in an upward direction (the air over the village square often shimmers in the noon heat) and these currents tend to carry the sound away from the ground. Sound seems to carry better over water and it is noticeable how each Lokele village invariably arranges its largest drums on the top of the river bank perpendicular with the beach and with the low-toned lip facing up-river.”

- F. Carrington, Talking Drums of Africa (New York, NY: Negro Universities Press, 1969), 29.

[28] “First of all, there is usually an opening signal or alert. In the Kele drum language this usually consists of several repetitions of high note – low note, high note – low note, represented in speech by the drummers themselves ki kε, ki kε.

[…]

he concludes with a series of low notes, sometimes terminated with a little flourish on both notes of the drum to characters his own particular beating – a king of signature tune.

[…]

Messages lasting twenty minutes are commonly heard at Yakusu, and many messages are even longer.”

- F. Carrington, Talking Drums of Africa (New York, NY: Negro Universities Press, 1969), 53–4.

[29] “The device of low frequencies eliciting an emotional response has been used since humans first tried to understand their place in existence through creative expression. It is the sound made by balls of lead dropped onto stretched annual skins to signify the intervention of the Gods in classical Greek tragedy. It is the thunder sheet in nineteenth century melodrama, part of the almost compulsory storm sequence that worried and nagged at the existential nerve of the new industrial landscape.

In film too, the archetypal sound is used to make the watcher sensitive to the action on screen. Sound is not confined to the visual frame and therefore enjoys a greater freedom of expression, particularly when it is contextualised by diegetic elements.”

Davies, Rhys, “The Frequency of Existence: Bill Viola’s Archetypal Sound,” in The Art of Bill Viola, ed. Chris Townshend (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 144.

[30] “SOUNDMARK: The term is derived from landmark to refer to a community sound which is unique or possesses qualities which make it specially regarded or noticed by the people in that community.”

- Murray Schafer, The Tuning of the World (New York, NY: A. A. Knopf, 1977), 274.

[31] “Accordingly, aural architecture refers to the properties of a space that can be experienced by listening. An aural architect, acting as both an artist and a social engineer, is therefore someone who selects specific aural attributes of a space based on what is desirable in a particular cultural framework.

[…]

In describing the aural attributes of a space, an aural architect uses a language, sometimes ambiguous, derived from the values, concepts, symbols, and vocabulary of a particular culture.“

Barry Blesser and Linda-Ruth Salter, Spaces Speak, Are You Listening? (Cambridge, MA; London, England: The MIT Press, 2007), 5.

[32] “The tambura is a drone instrument, usually of four or five strings, that, due to the particular constructions of its bridge, amplifies the overtone or harmonic series of the individual notes in each tuned string. This series of overtone notes describes the scale that the musicians are playing. It produces the familiar complex buzzing or ringing sound that has become for many foreigners “that Indian-music sound.” Therefore, when the main musicians play, they are pulling notes out of this already ongoing sound field, the drone. There is no silence. The musicians say that this concept relates to the Hindu philosophy of the cosmic sound or vibration, “Om,” which is ever present, going on without beginning or end, everywhere within the universe, and everything proceeds from it.”

Bill Viola, “The Porcupine and the Car,” Image Forum 2, no. 3 (January 1981): 48.

[33] Bill Viola, Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1995), 155.

[34] In Science of the Heart (1983), Viola’s own heart beat is used directly, a reminder of our mortality, its sound filling the room, manipulated to speed up and slow down in time. In his 1986 work I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like, Viola employed ceremonial Hindu drumming to represent the central function of the beating heart in human experience. In the middle point of Viola’s installation rooms at the 1995 Venice Biennale the audience were immersed in a diffuse soundscape of Viola’s body sounds, including his heartbeat.

[35] Bill Viola, “Science of the Heart (1983),” in Bill Viola: Installations and Videotapes (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1987), 49.

[36] “The citations in Viola’s work do not function as ends in themselves, but put one work in the context of others and of Viola’s creative work in general. They transfer the content of a work (or aspects of its meaning) to other works and thus appear as elements of a language or sign system which we come to understand by becoming acquainted with the totality of Viola’s oeuvre.”

Otto Neumaier, “Space, Time, Video, Viola,” in The Art of Bill Viola, ed. Chris Townsend (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 62.

[37] “Aboriginals could not believe the country existed until they could see and sing it – just as, in the Dreamtime, country had not existed until the Ancestors sang it.

‘So the land’, I said, ‘must first exist as a concept in the mind? Then it must be sung? Only then can it be said to exist?’

‘True.’

‘In other words, “to exist” is to be perceived”?’

‘Yes.’”

Bruce Chatwin, The Songlines (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2012), 12.

[38] Bill Viola, Talking Drum (New York, NY: Whitney Museum/Flammarion), 1997.

[39] Bill Viola, Talking Drum (New York, NY: Whitney Museum/Flammarion), 1997.

[40] Astra Price, The Talking Drum – Bill Viola (Liner Notes), London: The Vinyl Factory in collaboration with Bill Viola studio, and Blain|Southern, 2015.

[41] “The dominant auditory perception of a large space is spaciousness, a scientific label for experiencing enclosed spaces. Aural spaciousness is the sensation of being inside the music rather than separate from it, analogous to swimming underwater rather than being sprayed with a garden hose.”

Barry Blesser and Linda-Ruth Salter, Spaces Speak, Are You Listening? (Cambridge, MA; London, England: The MIT Press, 2007), 231–232.

[42] Bill Viola, Talking Drum (New York, NY: Whitney Museum/Flammarion), 1997.

[43] Bill Viola, Talking Drum (New York, NY: Whitney Museum/Flammarion), 1997.

[44] “[T]he archive, as distinct from a collection or a library, constitutes a repository or ordered system of documents and records, both verbal and visual, that is the foundation from which history is written.”

Charles Merewether, “Introduction: Art and the Archive in The Archive “(London, England; Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006), 10.

[45] Wolfgang Ernst, Art of the Archive in Kunstler.Archivneue Werke Zu Historichen Bestanden, edited by Helen Adkins (Koln: Walter Konig, 2005), 101.

[46] Here, we understand media to be both plural of the material/immaterial medium, a means of mass communication (Internet, newspapers, radio and television) and as digital files related to computers and digital storage systems used to store or transmit data, also referred to as delivery technologies (hard disks, networked storage etc).

[47] “To visit the storeroom, where objects dwell cut off from critical aura, is to contemplate art in a state of temporal remission.”

Ingrid Schaffner, “Deep Storage,” Frieze 23 (1995): 58.

[48] See: Gilles Deleuze, and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, translated by Brian Massumi (New York, NY: Continuum, 2007).

[49] ‘“Which is to say, the site is now structured (inter) textually rather than spatially, and its model is not a map but an itinerary, a fragmentary sequence of events and actions through spaces, that is, a nomadic narrative whose path is articulated by the passage of the artist. Corresponding to the model of movement in electronic spaces of the Internet and cyberspace, which are likewise structured as a transitive experiences, one thing after another and not in synchronic simultaneity, this transformation of the site textualises spaces and spatialises discourses.”

Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another (London, England; Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004), 29.

[50] See Janet Cardiff’s Forest Walk (1991) and Christina Kubisch’s Electrical Walks, a project that Kubisch began in 2003.

[51] “The literal site is, as Joseph Kosuth would say, in situ; it is an actual location, a singular place. The artist’s intervention conforms to the physical constraints of the situation, even if (or precisely when) it would subject this to critique. The work’s formal outcome is thus determined by a physical place, by an understanding of the place as actual. Reflecting a perception of the site as unique, the work is itself “ unique”. It is thus a kind of monument, a public work commissioned for the site.”

James Meyer, “The Functional Site; or, the Transformation of Site Specificity,” in Space, Site, Intervention, ed. Erika Suderburg (Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 24.

[52] “In contrast, the functional site may or may not incorporate a physical place. It certainly does not privilege this place. Instead, it is a process, an operation occurring between sites, a mapping of institutional and textual foliations and the bodies that move between them (the artist’s above all). […] It is a temporary thing, a movement, a chain of meanings and imbricated histories: a place marked and swiftly abandoned.”

James Meyer, “The Functional Site; or, the Transformation of Site Specificity,” in Space, Site, Intervention, ed. Erika Suderburg (Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 25.

[53] Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another (London, England; Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004), 29.

[54] Crocheted Environment was originally named Womb Room, and was created by Wilding for the seminal 1972 Womanhouse exhibition put together by the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of Arts: “But on the other hand, to recreate the work as an independent art object for a white cubic space in the Bronx Museum also meant voiding the meaning of the work as it was first established in relation to the site of its original context.” Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another (London, England; Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004), 43.

[55] “However, as the Ace Gallery case amply reveals, despite withdrawal of such signifiers, authorship and authenticity remain in site-specific art as a function of the artist’s “presence” at the point of (re)production.”

Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another (London, England; Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004), 39.

[56] Barbara London, “Bill Viola: the Poetics of Light and Time,” in Bill Viola: Installations and Videotapes (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1987), 19.

[57] William Furlong, “Bill Viola,” Speaking of Art: Four Decades of Art in Conversation, with an introduction by Mel Gooding (London: Phaidon Press, 2009), 155.

[58] Henri Bergson quoted in Peter Hartocollis, Time and Timelessness: The Varieties of Temporal Existence, A Psychoanalytic Inquiry (New York, NY: International Universities Press, 1983), 6.