Alan Dunn

Senior Lecturer, Fine Art and MA Art & Design, Leeds Beckett University

Email: a.dunn@leedsbeckett.ac.uk

Web: www.alandunn67.co.uk

Reference this essay: Dunn, Alan. “Curating the Sound of the Word Revolution.” In Sound Curating, eds. Lanfranco Aceti, James Bulley, John Drever, and Ozden Sahin. Cambridge, MA: LEA / MIT Press, 2018.

Published Online: December 15, 2018

Published in Print: To Be Announced

ISBN: 978-1-912685-55-4 (Print) 978-1-912685-56-1 (Electronic)

ISSN: 1071-4391

Repository: To Be Announced

Abstract

Dr. Alan Dunn, Senior Lecturer at Leeds Beckett University, reflects upon his sound art project Artists’ uses of the word revolution in relation to pedagogy, curating and distribution. The project formed part of a new pedagogic model established at Leeds between Dunn, Chris Watson and visual art students, exploring the spaces between sound recording and sound recordings, and between lecturing and administration. The curatorial methodologies deployed throughout the project considered some of the core behavioral drivers that lead professionals and amateurs to return to the record button and why we often revisit the same themes when recording. One of these themes is explored in this text, namely a desire to (sound like one wishes to) change the status quo through the sound of the word ‘revolution’. Dunn curated the collection non-hierarchically, using material from art lecturers and students, artists, archives and other professionals. The work was disseminated in phone boxes, handed out on streets, and more formally shared at events at the Sharjah Art Foundation, Liverpool Art Prize, Auricle Sonic Arts Gallery in Christchurch, Cirrus Gallery in Los Angeles and the ICA and DeptfordX in London.

Keywords:

Non-hierarchical curating of sound art, pedagogy, Chris Watson, Douglas Gordon, revolution, Fluxus, Leeds, archiving

The Sounds of Revolution Forming

In the late 1960s, a group of artists associated with the Fluxus movement including Robin Page and George Brecht arrived in Leeds to lecture part-time. Reflecting upon the period in a 2013 interview with myself, Page described it as a wild and free experimental mêlée of improvised sound, drinking, nudity and a “we just did stuff” [1] mentality in which artists and students worked together on music and musicians worked on art projects. Spaces between roles and disciplines were eroded as staff and students collaborated, performed, organised, educated, curated and handed out free texts and artworks in the high street. George Brecht had been taught by John Cage and shortly after I began lecturing in Leeds (commuting from Liverpool), I became interested in this lineage and Leeds’ pedagogic history of working between sound and visual art. Soft Cell’s Marc Almond studied Fine Art in Leeds during the late 1970s and artist Peter Suchin’s unpublished article [2] on his time studying there between 1979-82 lists some notable visiting lecturers as Throbbing Gristle’s Genesis P. Orridge and Factory Records’ founder Anthony Wilson. These art-sound-music crossovers could serve as the inspiration for further experimental interrogation into the spaces between sound, curating and pedagogy.

The notion of the ‘between’ became increasingly important to my research, and I undertook a PhD by Previous Publication (2008-14) entitled The sounds of ideas forming, the relationship between sound art and the everyday. In this context I took the between as a space between A and B into which new cultural activity could be located. In particular I was interested in those spaces within the everyday, such as the commute or high street, and my PhD examined instances of locating sound art into these contexts. An example included my ‘Soundtrack for a Mersey Tunnel’ CD that was distributed exclusively to commuters of that thoroughfare on bus number 433 (a direct link to John Cage’s 4’33”), the same bus I used between home and travelling to Leeds to lecture.

I began lecturing in Leeds in 2007, attaining a part-time 0.6fte contract two years later. Allan Davies, Senior Advisor to the Higher Education Academy, described part-time practitioners as “an interface between the students and both the real world of work and contemporary discourses in the field.” [3] The 0.6fte contract is an interesting splice through one’s life, equating on average to three days’ employment each week and many artists on such contracts decide to commute rather than relocate. Despite in many ways being an ideal balance between life and work, a 0.6fte contract inherently creates a constant state of flux, of never quite being in one place nor the other. It is nomadic, and to adopt a phrase used by curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist to describe his own practice, it represents “a position of in-between-ness.” [4]

Within my part-time lecturing role I developed a model for research that explored sound art, curating and pedagogy, drawing upon moments of cultural significance to curate CD projects around seven distinct themes, namely silence, water, revolution, grey, catastrophe, background and numbers. Each collection drew together archival material, original soundworks by professional artists and new compositions by our visual arts students. In this article, I shall outline the contribution I made in evolving this use of sound within a visual arts course at Leeds Beckett University [5], before considering one of those themed CDs, namely Artists’ uses of the word revolution (2009).

The sound of the art school

In early 2009 I invited sound recordist Chris Watson to run the first of his now annual masterclasses for visual arts students in Leeds. Watson and I had first collaborated in Liverpool on a tenantspin project entitled A Winter’s Tale [6], an experience that opened my ears to working with sound. I was inspired by the breadth of his activities, ranging from the founding of avant-garde English music group Cabaret Voltaire to his award-winning natural history sound recordings for Sir David Attenborough. Watson also records as a solo artist, and shortly after he undertook his second masterclass at Leeds, he released his seminal album El Tren Fantasma (Ghost Train). The album was composed from field recordings made by Watson in Mexico while working on the BBC programme Great Railway Journeys in 1999 and included the track El Divisadero. [7] The track was an evocation of the early industrial sound of Cabaret Voltaire, shifting effortlessly between foreground and background, dropping out from the heaviest dub and returning with a heavenly choir floating on a bed of railway drone. It is underwater, the Doppler effect and, in my opinion, in the background of El Divisadero could possibly be heard masterclass recordings that Watson, myself and students made under the rail bridge by the Leeds & Liverpool Canal. If not, then the sound of El Divisadero definitely acknowledged the experience of us in Leeds at 2am listening to early-morning rolling stock and capturing a rhythm of the city from a new perspective.

Aldous Huxley, speaking at Berkeley Language Center in 1962, stated: “All revolutions have essentially aimed at changing the environment in order to change the individual.” [8] By inviting Watson to Leeds, and inspired by Huxley’s quote, I wanted to create a new listening culture at the art school, altering the environment to stimulate the students. Some had been working with sound prior to 2009, but their studies had lacked direction and conceptual thinking, let alone appropriate equipment. In the art studios, Watson inspired the staff and students, teaching us how to record, why to record, how our ears work, how to listen to backgrounds and the importance of both the popular and the avant-garde. El Divisadero took the prosaic and transformed it into the abstract. Watson shared with us a tale of recording the sound of his fridge using a 50p contact microphone and selling it to an international games company as the accurate sound of a nuclear reactor. Both of these were important as they demonstrated to students the ability to expand the range of a recording. Leeds could sound like Mexico and your fridge like North Korea. He also gave staff and students practical advice, recommending recording and playback equipment for the university to purchase, including binaural microphones, WAV recorders and surround-sound Genelec speakers. To this day, Watson returns annually to Leeds Beckett, and on each occasion we select around fifteen students from all levels to work with him in the studio and in the city, learning new skills and using our newly developed ear muscles to explore sonic and social issues, while publishing some of the audio results on the CDs.

Artists’ uses of the word revolution (2009)

You Say You Want a Revolution. We at the Leeds School of Art, Architecture and Design have been having a quiet revolution. There are no hierarchies on making here; this is about turning from facing inwards to facing outward, working with communities and community. Vive la revolution! [9]

I became interested in what the relationship between art schools, the word revolution and the everyday might sound like. In summer 1968 for example, while Hornsey College of Art students protested against the education system as a noteable revolutionary act, five miles away in Abbey Road Studios John Lennon and Yoko Ono took the second half of the song Revolution [10] and extended it with tape loops and live radio feeds to create Revolution 9. [11] The journalist David Quantick described Revolution 9 as “literally subversive, an avant-garde recording that can be found in millions of houses, apartments, wine bars and other settings.” [12] Lennon himself referred to it as “an unconscious picture of what I actually think will happen when it happens; that was just like a drawing of revolution.” [13] Revolution 9 is a collage of spoken word, library recordings and backward sounds, but it does not contain the sound of the word revolution.

Academic Evan Mauro notes “the story of the twentieth-century avant-gardes is invariably a story of decline, from revolutionary movements to simulacra, from épater le bourgeois to advertising technique, from torching museums to being featured exhibitions in them.” [14] Each year I play Revolution 9 to our First Year students as a sonic background, a simulacra of revolution onto which they may one day record, loop, broadcast, splice, scream or whisper their own sounds of the word.

Developing this further, I set out to explore how creatives from all eras and backgrounds had recorded the sound of the word. I curated a CD that was not actual revolution, nor revolutionary as in Hornsey, nor about revolution as Revolution 9. It was instead about the sound of the word revolution. Gathering material for the CD began in late 2008 with a prearranged call by myself to artist Douglas Gordon in New York. He did not pick up, but his answering service played The Internationale [15] and asked that the caller leaves a message. Over the next eight months I metaphorically created that message, collecting sound files for a journey through sixty-six geographic and thematic revolutions from Russia to China to Cuba to Ukraine, exploring the sexual, the technical and the industrial sound of the word. On each occasion, re-vo-lu-tion was whispered, proclaimed or screamed, through techno from Belarus, soul from Trinidad, punk from Spain and metal from Germany. Staff member James Chinneck recorded the sound of the word being spray-painted onto an art school wall and Marion Harrison’s spoken word piece collaged The Beatles with the Velvet Revolution. Peter Suchin dissolved the word into Rest-vole-Luton-tinted-ontic. I invited our students to develop their own sounds of the word using the new recording equipment. Second year student Samantha Wass created a delicate piece entitled Information Revolution built from recordings of paper, typewriters and laptops and Mark Whitford used Watson’s bat detector and contact microphones to great effect on revolution mw 2.44khz.

I simultaneously secured permissions to include the sound of the word as recorded by Paul Revere & The Raiders, Herbert Marcuse, Sarah Jones, Black Panthers, Marcel Duchamp, Aldous Huxley and Chumbawamba. As I neared a complete collection, I wanted to test whether (sound) artists could work instinctively and put out a call for works that included the word revolution but gave only six hours until the deadline. Fourteen pieces arrived and I included six on the CD, one of which I decided not to listen to before inclusion, despite not knowing the artist; an exercise in blind (deaf) curating and I have worked hard not to ever listen to that track since. Viva la resistance! I curated what curator Clementine Deliss called “a treasure hunt characterised by cryptology and the absurd.” [16] Negotiations with Southern Records over the use of Crass’ Bloody Revolutions [17] took so long that I had to abandon it. Likewise, negotiations with Chris de Burgh hit a brick wall. [18] On all occasions, I wanted to use content with permission, to have dialogues with artists and content holders and to get closer to the original creative impulse of the pressing of the record button. Musician and critic Seth Kim-Cohen writes about the verb ‘to record’ as a curious composition of which “the prefix re- means ‘again’ or suggests a backwards movement. The root ‘cor’ comes from the Latin for the heart (“le coeur”). To record, then, is to encounter the heart again or to move back to the heart. The romantic implication is that a recording captures and replays the heart of its source.” [19] This is an interesting proposition and in a similar vein I wished to remind people that they had once recorded the word revolution and, rather than simply culling together a playlist from readily available material, I wanted a series of human communications within the endless sea of data. I wanted these artists, poets and musicians across the globe to know I was somewhere between Liverpool and Leeds and our students were in Leeds, and we were all thinking about the sound of the same word.

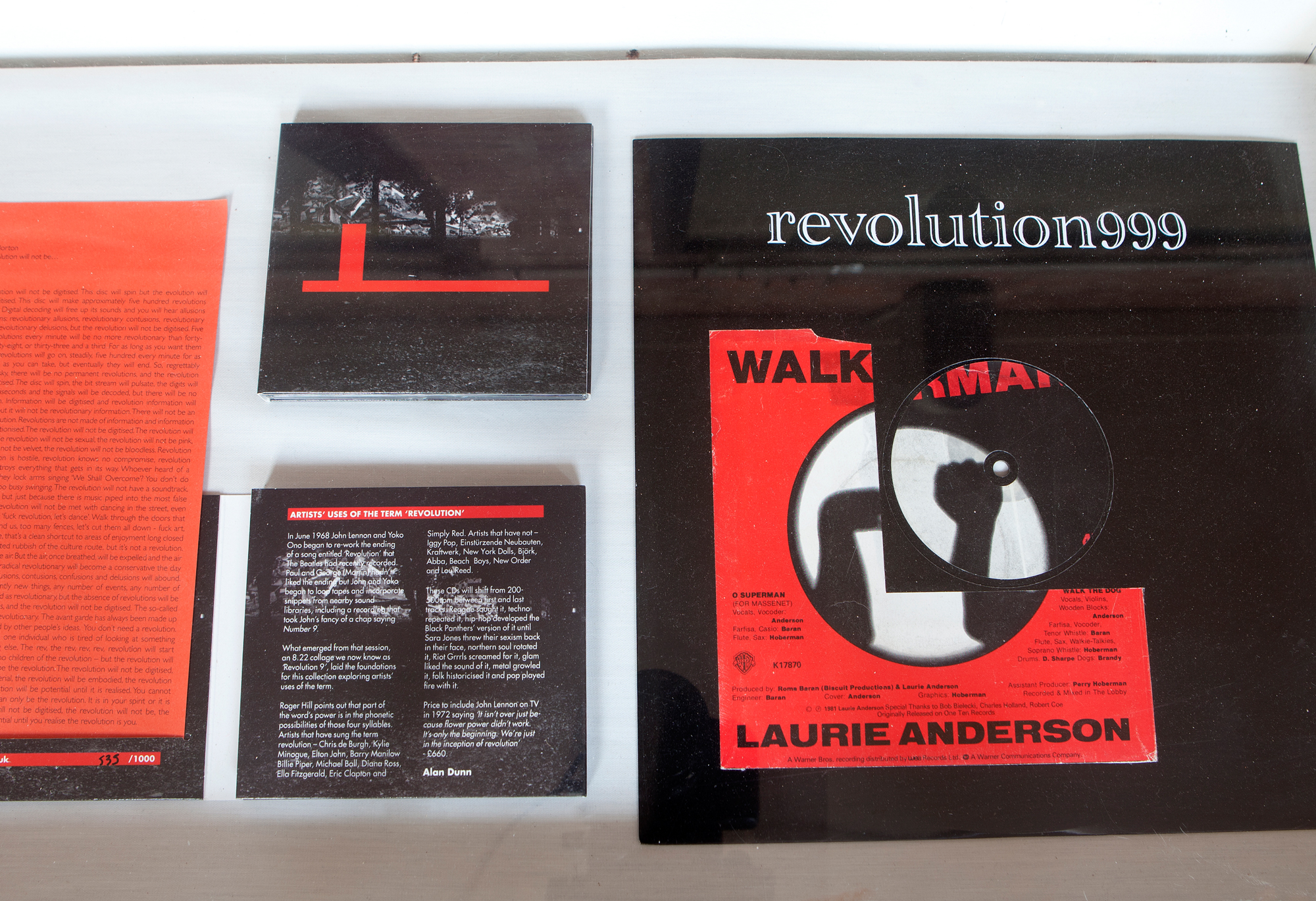

Art Schools on Fire

I used the CD design to celebrate moments of irony. Behind the disc was hidden a list of commercial businesses in Liverpool and Leeds that used the word revolution. TV company ITN wished to charge £660 to include five seconds of Lennon speaking about revolution from 1972 but I declined and instead wrote about it as part of the design. This was placed next to a list of more middle-of-the-road artists who had recorded the word. [20] The more I heard the word uttered, the more diluted and hollow it became.

Graphics student Lisa Novak and I chose for the cover an image of a former art school, one visible from the 433 bus, situated in Central Park, Merseyside. The building had been neglected by Wirral Council and suffered an arson attack in 2008. Bizarrely, the Council then illuminated the remains; a school made rubble by the neglect of bureaucrats rather than the fire of the film If [21] where revolution springs from within an English educational institution. From the University of Hawaii, Rich Rath provided The revolution will not be streamed as homage to Gil Scott-Heron’s The revolution will not be televised. [22] Critic Dorian Lynskey notes of the Scott-Heron original that it “lets his sly sense of humour breathe. His subject was a revolution of the mind, not the gun.” [23] We designed a booklet to list all the tracks and I invited former Leeds academic and artist-curator Derek Horton to write a new manifesto entitled The revolution will not be. We slipped it in behind the booklet to carry from one place to another as the art school in Leeds changed buildings. The Fine Art department had been based in H-Block before moving into the custom-built Broadcasting Place in 2009. The move greatly contextualised my research project and lent it an additional poignancy, whilst the CD also acted as a statement of the importance of sound within the Fine Art department in its new location.

The education revolution

The revolution CD was a complex artistic form with a tight quality control, a black humour and a broad curatorial range. Within the CD design I credited all the university administrators and finance workers who had assisted with some of the more straightforward curatorial activities. In emerging from an art school in transition with new tools and insights into the recording process, the CD was a powerful message about pedagogic possibilities. At the time Leeds Beckett was using synoptic assessment to help “make connections between modules, increase the level of student engagement and provide teaching staff with the opportunity to adopt a holistic approach to delivering modules” [24] and I saw both the curated sound projects and the Chris Watson masterclasses as sitting within this undoing of an overly modularised curriculum. In June 2012, Amy Leech and Joe Finister, both participants in two masterclasses and contributors to another of my CDs, A history of background, [25] graduated with First-class Honours Degrees for their work in sound. Finister’s pieces were rooted in his passion for dubstep that Watson encouraged him to develop into even more cinematic surround soundscapes. Leech created intimate recordings for her animations, including some recordings of fishermen’s maggots. These so delighted Watson that when appearing on Bang goes the theory [26] and asked to demonstrate the quietest sound he could record, he chose maggots.

The success of arts education within the institution ebbs and flows, and at certain points particular sets of student work achieve something unique. In May 1972, such was the currency of Leeds’ art education that the ICA in London staged an exhibition of student works entitled Students at Leeds. Forty years later, the work of Leeds students was returned to the ICA when I was commissioned to create a 20-minute mix of The sounds of ideas forming as part of their Soundworks project within Bruce Nauman’s DAYS exhibition. In the upstairs gallery, a large black box housed an iPad with a series of audio works played through a central speaker. My piece included content, including some revolution pieces, from Leeds students, all of whom had worked with Watson. [27]

As a city, Liverpool has created a rich cultural identity from its history of beat poets, popstars and punks. [28] An institution such as Leeds Beckett University can equally explore its cultural history beyond its own immediate physical surrounds. It can, for example, recall and celebrate Patrick Heron’s 1971 article that described Leeds as “the most influential school in Europe since the Bauhaus.” [29] In my own practice, as outlined previously, I have aimed to encapsulate and highlight some of these histories of Leeds as part of the core concepts that underpin my work. In the world’s leading journal on underground music and sound art, The Wire, artist and curator Bruce Davies wrote of my practice that it “seems to share similar non-material concerns as those working at Leeds Polytechnic in the 70s … Dunn has also established a yearly masterclass at Leeds Metropolitan University, with sound recordist Chris Watson: Yorkshire’s past extending a helping hand to the country’s potential future.” [30] I include Davies’ comment here to demonstrate both the importance of publicizing pedagogic practice in critical contexts such as The Wire, and of acknowledging collaborators such as Watson.

Revolutions Per Minute

The choice of the publication format in itself was fundamental in order to explore finite curatorial decisions and the creation of moments of encounter in which sound art interjected into everyday life, much as Revolution 9 entered living rooms. The decision to theme each volume and to work non-hierarchically was also a fundamental aspect of my research. Whilst a sound archive such as UbuWeb is incredibly valuable and browsing it randomly can lead to interesting discoveries, it makes no attempt at finding themes across generations. I was interested in a different archival model that would allow a finite set of themed recordings to interact with the everyday. In doing so, new knowledge could be gained about recorded sounds located in specific contexts. To achieve this, the CD was chosen as my publishing format, despite digital music sales already accounting for 15% of the market in 2008. As Gustin reports, [31] by 2011 digital had in fact surpassed physical sales, but the CD had a size, weight and unit cost that made physical distribution feasible. The sounds of ideas forming, including Artists’ uses of the word revolution, in CD form is thus not an open-ended archive but a set of finite curatorial decisions within seven 74-minute collections.

The CD as a format may have lacked the gravitas of vinyl or the instant gratification of the MP3, but it did open up a conceptual space somewhere between analogue and digital. Analogue has a relationship with fixed timescales whereas the digital is built around snapshots and acceleration. Content uploaded to Facebook for example takes an average of 24 milliseconds to reach its huge servers in Sweden. Taken in isolation, the digital realm lacks any between-ness. It is on or off, A or B. Kahn & Dyson refer to this condition as “the zoom … that is to data transfer what the tunnel is to commuter throughput. The quicker the zoom the more transcendent, where all has been burrowed through, where time and space have collapsed, and the passage to another plane has been completed.” [32] My research explored a series of betweens as counters to these collapsed dimensions; real journeys through tunnels and new connections between content. One doesn’t zoom through the Mersey Tunnel. On the 433, it takes on average 2’33”, the length of every track on that CD. My CDs also asked us to think about the time and spaces we have to produce, share and consume recorded sound in an era of hyper-acceleration.

Remix, Remodel, Redistribute

Copies of the revolution CD were left in New York phone boxes, handed out in London streets and have featured in around forty international events. [33] I developed the audio content further, extracting combinations of tracks to present in other contexts, including the Cultural Hijack project curated by Ben Parry (London, 2013), for which I created an iPad playlist featuring remixes and out-takes. For /seconds, curated by Peter Lewis and Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi (Sharjah Art Foundation, UAE, 2014), I combined extracts from the CD with snippets from movies in which the word is heard. [34]

Thinking about the sound of the word revolution began with listening to Revolution 9, imagining the avant-garde in the living room and considering Fluxus in Leeds. Traversing Deptford High Street in September 2013 as part of the DeptfordX festival, I handed out free copies of the revolution CD to passers-by, creative workers and shopkeepers. The Mayor of Lewisham accepted a copy and spoke of the housing revolution of the 1970s that gave birth to bands such as Dire Straits and Squeeze and artist Bob and Roberta Smith spoke of the revolution needed within art education. The day-long event encapsulated all of my research interests around finding thematic routes through recorded sounds, drawing lines between content and locating audio content (CDs) in social settings (the high street) to observe what happens.

Artists’ uses of the word revolution (Reprise)

Revolution 9 laid the sonic backdrop for the word, Douglas Gordon asked us to leave a message about it and students learned new techniques for recording the word. As BBC Radio Merseyside broadcaster Roger Hill noted, the four syllables of the word make it particularly pleasing acoustically: RE-VO-LU-TION. The word has been recorded on vinyl, at 33 or 45 revolutions per minute and CDs at between 200-500rpm. Artists’ uses of the word revolution reminds us that pressing the record button is a return to the heart, a capturing of the sound of the word revolution as a rally cry or paean for resistance and change. It is the result of someone wanting to make change and learning how to press the record button in order to make the sound of change and in doing so perhaps changing by learning to press the record button properly.

My experience in creating and curating Artists’ uses of the word revolution also led me to understand that the ‘between’ is a critical area in which to operate. When it is possible to draw a link between two points on a temporal and spatial range, one can make insightful work that functions at particular defined points on the line. I contacted artists and created real space and time between students and professional artists, while drawing a line between them all recording the same word. In a climate of hyper-acceleration and instant digital gratification, we are in danger of missing out on what Miller termed: “a rhythm to the space between things.” [35] Curating the artist-student-archive CDs was a simple formula from which to proceed and it captured the imagination of all the contributors. It was not only employing sound as an investigatory medium, influenced by the practice of Watson, but also about navigating and producing novel histories. It was a simple structure that looked back at historical contexts, analyzed the present, and ventured into the future. It was about drawing lines as a basis for creativity: observing and connecting.

Finally, if there is a pedagogic manifesto that arose from Artists’ uses of the word revolution, it is this: a part-time role can afford the artist-educator the time and space necessary to occupy the space between things – to trace lines from one thing to another. We must develop pedagogic, artistic and curatorial models that balance a learning-in-process equally with a critical consideration of product. We, as artist-educators, must work with artists, galleries and public contexts to ensure that both the taking part and the results are of the highest calibre. We must nurture a holistic, experiential and synoptic environment within the institution even when the institution itself is in a constant state of flux. [36] We must expand the creative tools we utilize, working creatively against financial constraint. Finally, we must take staff and students on innovative conceptual journeys amongst the cultural histories they operate from, inspiring and not restricting, whilst encouraging them to remain porous and reactive to the ever-changing circumstances of their contemporary environment.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by Leeds Beckett University. For further information on The sounds of ideas forming, please see http://alandunn67.co.uk/ADCD.html.

Author Biography

Dr. Alan Dunn (born Glasgow 1967) studied at Glasgow School of Art and The Art Institute of Chicago. His main research interests lie in the relationships and spaces between contemporary art and the everyday, particularly in non-gallery contexts. As a student, he initiated and curated the Bellgrove Station Billboard Project (1990-1) at an east end railway station in Glasgow, presenting new works by Douglas Gordon, James Kelman, Brigitte Jurack, Pavel Büchler, a hypnotherapist and an urban planner. As lead artist on the Internet TV project tenantspin (2001-7) with the Foundation for Art & Creative Technology in Liverpool, he developed an internationally recognised and sustainable community media project. tenantspin enabled elderly high-rise residents to present live webcasts on cultural and political issues with a range of collaborators including Bill Drummond, Hillsborough Justice Campaign, Gustav Metzger, 40 Years of Fluxus, Jayne Casey, Mike McCartney, Superflex, Skip McDonald, Foreign Investment and Chris Watson. Between 2008-12 Dunn curated the 7xCD opus The sounds of ideas forming, bringing together soundworks from archives, art students and established practitioners including The Residents, David Bowie, Einstürzende Neubauten, Yoko Ono, Carol Kaye and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry. Dunn has exhibited widely, including Soundworks as part of Bruce Nauman’s DAYS (ICA), The Liverpool Art Prize, Open Network at Cirrus Gallery (Los Angeles) and has broadcast on ResonanceFM and the BBC. He is joint arts-editor with Ben Parry of the online journal Stimulus Respond. Dunn lives in Liverpool and currently co-runs the MA Art & Design course with Peter Lewis at Leeds Beckett University.

Notes and References

[1] Robin Page, Leeds 1967-70, MP3 file and email (Personal communication, 13 March 2013).

[2] Peter Suchin, Some Visiting Lecturers at Leeds Polytechnic, 1979-82 (Unpublished text, London, 2011), 1.

[3] Allan Davies (ed) Enhancing Curricula: Contributing to the Future, Meeting the Challenges of the 21st Century in the Disciplines of Art, Design and Communication (CLTAD, London, 2006), 37.

[4] Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Alexander Dorner etc…. “everything is inbetween” (1998), http://www.thing.net/eyebeam/msg00373.html (accessed November 10, 2016).

[5] Leeds Polytechnic was formed in 1970 and included part of Leeds College of Art (once part of Leeds School of Art). The Polytechnic was re-designated as Leeds Metropolitan University in 1992. Fine Art was taught in H Block building until the move into Broadcasting Place in 2009. In 2014 the name changed to Leeds Beckett University. A key publication on this subject is James Charnley’s Creative License: From Leeds College of Art to Leeds Polytechnic, 1963–1973 (Lutterworth Press, 2015).

[6] Chris Watson, A Winter’s Tale (Audio installation. Liverpool: Foundation for Art & Creative Technology, 2005) and tenantspin (Online community art project, Liverpool, 2001-7), http://www.fact.co.uk/projects/tenantspin-the-incomplete-archive.aspx (accessed November 10, 2016).

[7] Chris Watson, El Divisadero (Sound recording, performed by Chris Watson on the album El Tren Fantasma [Ghost Train], Touch, 2011).

[8] Aldous Huxley, “The Ultimate Revolution” (Lecture, The Berkeley Language Center, University of California, March 20, 1962).

[9] Dr. Rebekka Kill, and Peter Ellis, Vive la revolution! (Degree Show publication, Leeds Metropolitan University, 2012).

[10] John Lennon – Paul McCartney, Revolution 1 (Sound recording, performed by The Beatles on the album The White Album, Apple Records, 1968).

[11] John Lennon – Paul McCartney, Revolution 9 (Sound recording, performed by The Beatles on the album The White Album, Apple Records, 1968).

[12] David Quantick, Revolution: Making of The Beatles – White Album (London: MQ Publications Ltd, 2002), 151.

[13] Jann Wenner, “John Lennon interview,” Rolling Stone, RS75, (1971), page unknown.

[14] Evan Mauro, “The Death and Life of the Avant-Garde: Or, Modernism and Biopolitics,” Mediations Journal of the Marxist Literary Group (Fall/Spring 2012-13), http://www.mediationsjournal.org/articles/the-death-and-life-of-the-avant-garde (accessed November 10, 2016).

[15] Eugène Pottier, The Internationale (musical composition, 1888).

[16] Paul O’Neill, ed., Curating subjects (Amsterdam: de Appel, 2007), 88.

[17] Crass, Bloody Revolutions (Sound recording, performed by Crass, 1980).

[18] For the Cultural Hijack exhibition of the CD, I created a short mash-up piece, Crass de Burgh.

[19] Seth Kim-Cohen, In the blink of an ear: toward a non-cochlear sonic art (London/New York, NY: Continuum, 2009), 117.

[20] Artists who have recorded the word revolution include Elton John, Barry Manilow, Kylie Minogue, Billie Piper, Eric Clapton, Michael Ball, Diana Ross and Simply Red.

[21] If…, dir. Lindsay Anderson, UK: Memorial Enterprises/Paramount (1968).

[22] Gil Scott-Heron, The revolution will not be televised (Sound recording, performed by Gil Scott-Heron on the album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, New York: Flying Dutchman/RCA, 1970).

[23] Dorian Lynskey, 33 Revolutions Per Minute; A history of protest songs (London: Faber & Faber, 2012), 239.

[24] Synoptic assessment enables students to show their ability to integrate and apply their skills, knowledge and understanding with breadth and depth in the subject. It can help to test a student’s capability of applying the knowledge and understanding gained in one part of a programme to increase their understanding in other parts of the programme, or across the programme as a whole.

[25] Alan Dunn, A history of background (CD, Dunn/Leeds Metropolitan University, 2011). This CD contained a broad curatorial range of recordings that considered the notion of background, including material from students, David Bowie, Brian Eno, Yoko Ono, Carol Kaye, Andy Warhol, Michelangelo Antonioni, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Muzak Orchestra, Einstürzende Neubauten and recordings from deep space.

[26] BBC, Bang goes the theory (TV programme, directed by Paul King, BBC1, 19 March 2012), http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00q6vht (accessed November 10, 2016).

[27] By the end of the exhibition The sounds of ideas forming was the eighth most popular of the 132 commissions that made up the Soundworks project, with over 1,200 listens. Other contributors included Brandon LaBelle, Scanner, Salomé Voegelin, Liam Gillick, Stewart Home, William Furlong and David Toop. https://www.ica.org.uk/projects/soundworks (accessed November 10, 2016).

[28] Into this Liverpool cultural context one could locate John Peel, Bill Drummond, Jayne Casey, Peter O’Halligan, Sean Halligan, Jeff Young, Philip Jeck, Deaf School, Adrian Henri, Roger Hill aka Mandy Romero, Ben Parry, Nina Edge, Paul Sullivan and Professor Colin Fallows. A valuable entry point into this lineage is Art in a City Revisited. Originally published in 1967, the book is a vital study of the arts and culture in Liverpool and was updated in 2009 by Julie Sheldon and Bryan Biggs, the latter of whom who has spent over 20 years at The Bluecoat Gallery curating exhibitions at points between the popular and the obscure.

[29] Patrick Heron, “Murder of the Art Schools,” The Guardian, October 12, 1971, page unknown.

[30] Bruce Davies, “Global Ear – Leeds,” Wire Magazine, Issue 323 (2011): 20. To clarify Davies’ term “Yorkshire’s past”, Chris Watson was born in Sheffield, the same Yorkshire region as Leeds.

[31] Sam Gustin, “Digital Music Sales Finally Surpassed Physical Sales in 2011,” Business Times, 6 January 2012, http://business.time.com/2012/01/06/digital-music-sales-finally-surpassed-physical-sales-in-2011/ (accessed November 10, 2016).

[32] Paul D. Miller, Sound Unbound: Sampling Digital Music and Culture (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008), 231.

[33] These included RADIO ON (Germany, 2015), Modern History (UK, 2015), Pitch and Patch (Austria, 2014), Transnational Express at The Auricle Sonic Arts Gallery (New Zealand, 2014), Radio Panik (Belgium, 2013), webSYNradio (France, 2012), Open Network at Cirrus Gallery (USA, 2012), Liverpool Art Prize (UK, 2012), Forest Fringe Travelling Sounds Library (UK, 2011) and nictoglobe radiotv (Netherlands, 2010).

[34] These included Alice in Wonderland, dir. Nick Willing, USA: Hallmark/NBC (1999), A Fistful of Dynamite, dir. Sergio Leone, Italy/Spain/USA: United Artists (1971) and Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, dir. Mel Stuart, USA: Paramount (1971).

[35] Paul D. Miller, Sound Unbound: Sampling Digital Music and Culture, 17.

[36] The 2008-14 period at Leeds Metropolitan University included changes to building, logo, Head of School, staffing structure, Faculty name, Faculty Dean, Vice-Chancellor, course name and the first moves towards changing the name to Leeds Beckett University.