Ian Stonehouse

Head of the Electronic Music Studios, Dept. of Music, Goldsmiths, University of London, London, UK.

Email: i.stonehouse@gold.ac.uk

Web: http://homepages.gold.ac.uk/ianstonehouse/Home.html

Dr. Lisa Busby

Lecturer, Dept. of Music, Goldsmiths, University of London, London, UK.

Email: l.busby@gold.ac.uk

Web: http://lisabusby.com

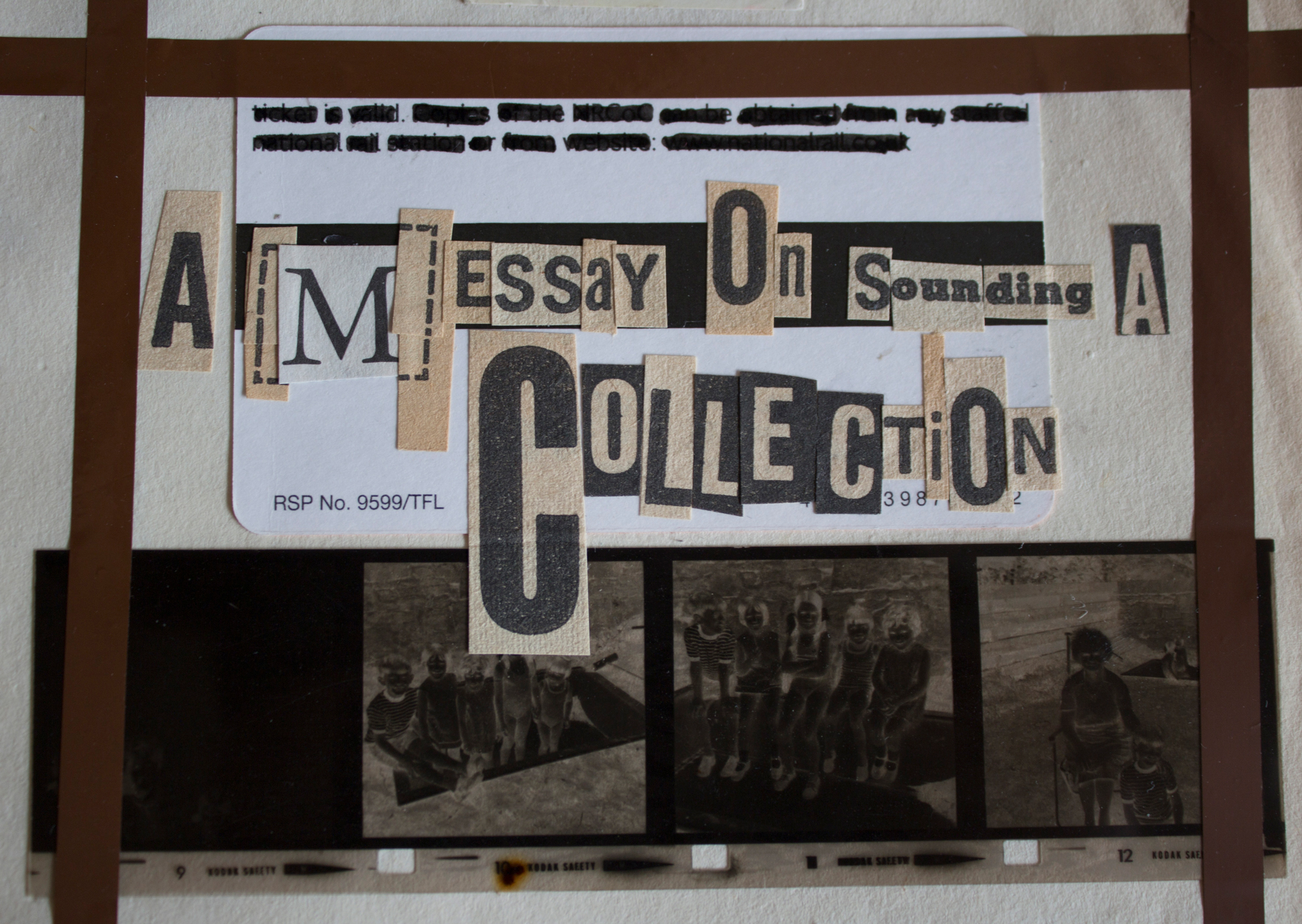

Reference this essay: Stonehouse, Ian, and Lisa Busby. “A Messay on Sounding A Collection.” In Sound Curating, eds. Lanfranco Aceti, James Bulley, John Drever, and Ozden Sahin. Cambridge, MA: LEA / MIT Press, 2018.

Published Online: December 15, 2018

Published in Print: To Be Announced

ISBN: 978-1-912685-55-4 (Print) 978-1-912685-56-1 (Electronic)

ISSN: 1071-4391

Repository: To Be Announced

Abstract

The purpose of this essay is to present and reflect upon our practice as sound artists and musicians who collect and perform with an array of objects and playback media. Our practice draws together interventions with books, records, reel-to-reel & cassette tape, music boxes, electronic circuits, field recordings, short wave radio transmissions, and sundry paper ephemera. These collections operate as both personal archive and score/instrument, either privately or in public performance (e.g. with noise/improv group Rutger Hauser). They also function as playful antidote to the administrative gravity of our professional careers. We can report no conclusions other than our vocabulary.

Keywords:

Archive, instrument, score, performance, sound, curation, collection, analog, digital.

Opening Comments

Every porpoise has a purpose.

“Of course not,” said the Mock Turtle: “why, if a fish came to me, and told me he was going a journey, I should say ‘With what porpoise?’ ”

“Don’t you mean ‘purpose’?” said Alice.

“I mean what I say,” the Mock Turtle replied in an offended tone. And the Gryphon added, “Come, let’s hear some of your adventures.” [1]

We reclaim the archive as a place of purp(is)use-less-ness, an anti-archive that “uses categories against themselves, exhibits their arbitrariness.” [2]

Background Reading

The situation we find ourselves in is quite normal. Camping out. Playing house in our own grown-up lives. Intense fantasies with objects and associated object//action leads to pitiful stuffing of every corner, every shelf, every visible and audible space with Collection.

‘Birmingham

74. (CO.37) between 6.50 and 6.55 in a well-to-do side street…

Later I passed a sedate elderly couple discussing loose pieces of coloured paper blown about the road.’ [3]

On Collection

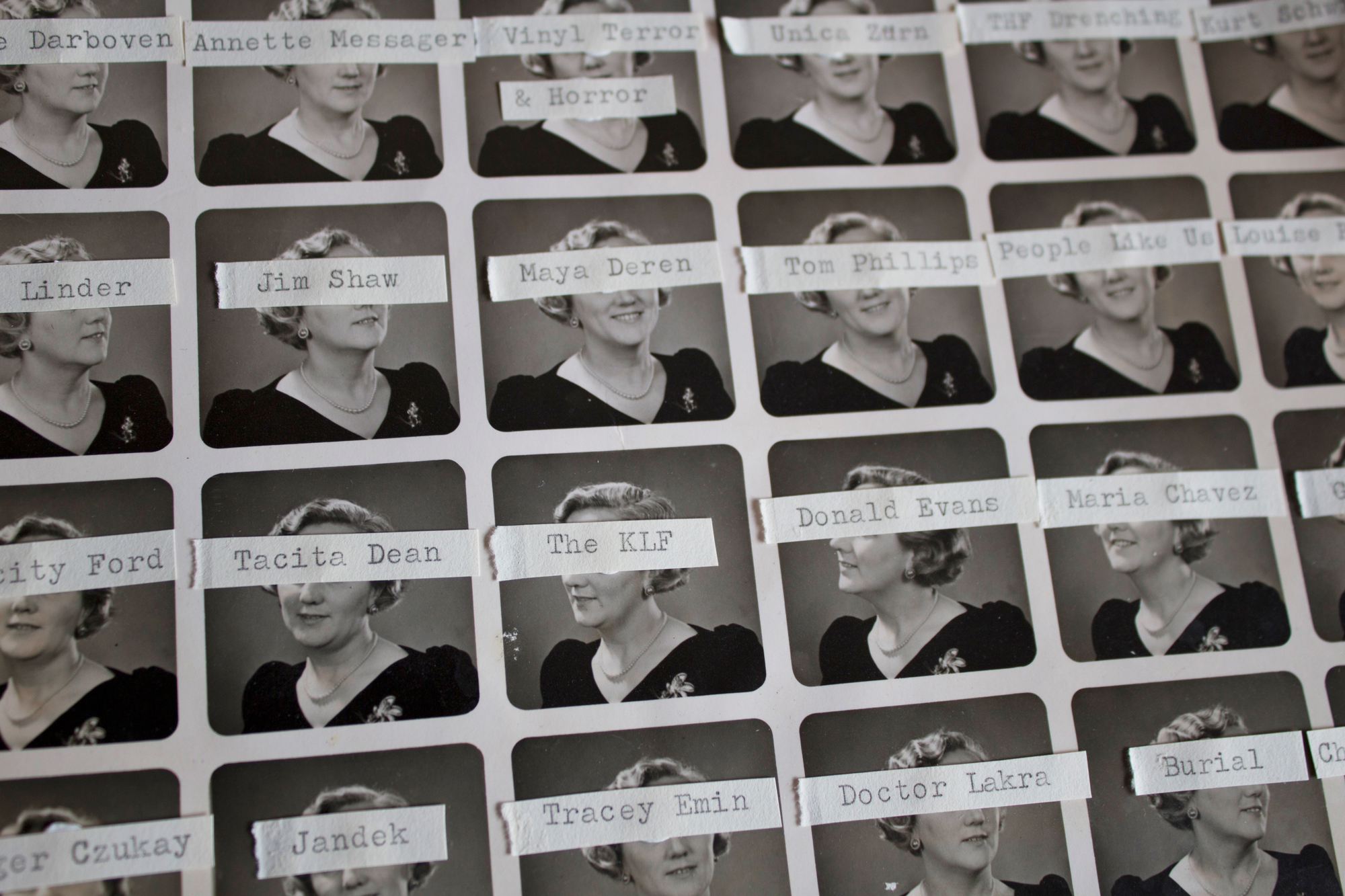

Collection is not curation. Collection is not preservation. These domestic reliquaries, these ephemeral groups of no economic value or worldly con-sequence do not speak in unanimous voice. No predetermined narratives guide their acquisition. To paraphrase Jennifer Wicke, [4] writing about Bram Stoker’s Dracula [5] as a figure of mass media consumption, we, as “Hunters and collectors” [6] sounding their collections, “are vampires at a banquet of ourselves… the one who bites and the one who is bitten, the one who types and the one who is typewritten.” [7]

On Sounding

All objects are sound generators, sound resonators, or sound instructors.

Objects may fall into more than one category.

Selected inventory

This list is representative of our instrumentation based on performances with Rutger Hauser, and as Rutger Hauser Digest, over the past two years.

- Books – read silently, read aloud, sung, uttered, referred to, written in.

- Book interventions (individual) – repositories for off-cuts of analog cassette or reel-to-reel tape, embedded record fragments, fitted with electronic circuitry, fitted with microphones, glued shut, hollowed-out, sewn into, used as scores.

- Books (collaborative/ongoing) – words erased, collaged, repositories for ephemera, found texts, images, maps.

- Dictionaries (single pages) – crossed out to reveal hidden text.

- Tape recorders (cassette) – played, broken, restored, hacked, shaken, stirred, becalmed.

- Reel-to-reel tape recorders – manually operated as delay device.

- Cassettes (blank) – recorded onto, played, listened to, paused, recorded over, hacked.

- Endless cassette – used live as analog samplers/loop playback.

- Cassette (pre-recorded) – collected, bought, borrowed, archived.

- Microcassette recorders – playback of pre-recorded or found tapes.

- Telephones – handset rewired with balanced connectors, used as microphone.

- Records (33, 45 & 78 rpm) – played, scratched, scraped, broken, collaged, fragments played, painted onto, collected, bought, borrowed.

- Synthesizers – played, rewired, bought, made, hacked, collected, lent.

- Pencils – fitted with analog tape playback heads (see 2), fitted with record stylus (see 12).

- Effects (analog & digital) – live sound processing or sound generators.

- Receipts – passed between performers with reference to – or acknowledgement of – ideas generated during performance, paper-based cues, suggestions and complaints.

- Typewriters – Amplified. Performance-based bureaucracy (see 16).

- Hair – amplified.

- Radios – short wave, commercial, air band – played live, recorded.

- Miscellaneous – personal collections, objects of value – e.g. music boxes, dice, fruit wrappers, garments, silver spoons, stamps, 35mm slides, furniture, cloth, blank papers, toys.

L(IAN)SA – Lisa & Ian Association for Non Sequitur Archives: Fifteen Initial Words for a Sound Collecting Vocabulary

- Archivist.

What, or who, is an archivist? This question was posed to members of the public in Leeds by a reporter for the Yorkshire Evening Post on Tuesday 1st June 1937, on the occasion of Leeds Corporation Libraries and Arts Committee appointing an archivist on a salary of between £275-325 per year.

A typist (school certificate standard): “Has it anything to do with Noah?”

An office boy (rising 15): “An architect’s assistant, isn’t it?”A clerk (female): “A man with bombs and things, or haven’t I got the right word?”

A clerk (male): “Sounds like a combination of religion, diet, and gymnastics.”

An army “bloke”: “No idea at all, old fellow.” [9]

- Moments

“All these moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain.” [10]A solar hour on a sundial is divided into 40 moments, making a moment equal to 90 seconds. Sound will travel approximately 30.88 kilometres in a moment, the average pop song will contain 2.52 moments (a mean of 3′ 47″). [11] If one was standing in the centre of London – traditionally held to be the Charing Cross on The Strand – a moment’s journey, sonically, along each of the four cardinal points of the compass would take you north to the middle of a small triangular field off Woolmers Lane near the village of Letty Green in Hertfordshire, east to a white caravan off Buckles Lanes north of a golf club in South Ockenden, Essex, south into trees on Cooper’s Hill Road in the village of Nutfield beside the M23 in Surrey, and west to the middle of Springate Field road in Langley, Slough, in Berkshire, besides the main railway line. In 2013, I began to plan a new sound work – Cardinal Moments – based around sound recordings to be made at these locations, and along the cardinal lines emanating from Charing Cross. Perhaps these would include interviews with the people I found. As of today, the piece remains unfinished and in exists only on the pages of a notebook and in a voice recording of the original idea, all duly archived and placed in a folder inside another folder (“Unfinished”) on a hard drive, awaiting a future moment of sounding or silent disposal.

What will die with me when I die, what pathetic or fragile form will the world lose? The voice of Macedonio Fernández, the image of a red horse in the vacant lot at Serrano and Charcas, a bar of sulphur in the drawer of a mahogany desk? [12]

- Descriptors.

Description of a system:

versatility, extensibility, sustainability, modularity, granularity, liquidity, transparency, relativity, unfamiliarity, remoteness, obscurity, chewy caramel center. [13]

- Identification.

“Chapter 4: Unique and Persistent Identifiers

4.1 Introduction

4.1.1 A digital sound recording, whether stored on a mass storage system or on discrete carriers, must be able to be identified and retrieved. An item cannot be considered preserved if it cannot be located, nor linked to the catalogue and metadata record that gives it meaning.” [14]

- The System.

The system must be capable of ingesting, merging, indexing, enhancing and preserving the user and their objects. - Domestic metadata.

Relational metadata-ta-dada must express parent-child relationships, the working-through of unresolved issues, be able to support the inaccurate mapping and instantiations of original carriers, intellectual capacity and interaction with domesticated recording equipment.

Classified advertisements…

“Young married couple would like to correspond by tape. Recorder speeds 3¼ in. and 7½ in. Box 247, Tape Recording Magazine, 1, Crane Court, E.C.4.” [15]

- Reconciliation.

The problem of reconciliation of databases persists in the capacity of the system to understand that items cannot be returned after opening, or expiration of the ‘listen by’ date.

- Naming conventions.

File naming conventions require careful discussion when making distinctions between the persistent and the occasional, the raw and the cooked, the original or the origial and a dog logically determined facsimile, typing error etc.

- The Infinite.

In Jorge Luis Borges’s short story “The Library of Babel,” [16] the author imagines an infinite library where no copy of any written work can ever be truly destroyed or lost, since there must be a copy that is identical in all respects other than, say, the addition of a comma on a single page, a difference so trivial as to render the two books identical. In this library (our universe?) librarians are frequently driven to madness by the impossibility of cataloguing an infinite circular space.

“Then the voice says: “ ‘Cause round things are . . . are boring [Silence . . . exhalation]’.” [17] These words appear at the end of Frank Zappa’s 1967 album Lumpy Gravy, [18] and in Frank Zappa: The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play [19] author Ben Watson equates the circularity of listening to records (the round things in question?) with the repetitive labour of mass production and the erasure of meaning, as a needle wears out a record groove. Watson imagines the ‘exhalation’ as a possible smoke ring, – another circle – wiring this theme into the Zappa/Mothers song “Sofa No.1” on One Size Fits All [20] (sofa being an anagram of the album title capital letters) and the cabalistic ‘Ein-Sof’, 11th Century poet philosopher Solomon ibn Gabirol’s ‘unending’ or ‘endless one’.

10. Artifacts/articles.

10.1. Furs are articles made from fur on the hide or pelt and articles of which such fur is worth more than three times as much as the next most valuable component.

10.2. Records are artifacts made from recordings the front or to one side and records of recordings are worth three times more than they are worth divided by the distance to the nearest charity store (NB: in America one substitutes thrift for charity).

“Alas, alas my son, a day will come when the sacred hieroglyphics will become but idols… those who will calumniate us thus, will worship Death instead of Life, folly in place of wisdom; they will denounce love and fecundity, fill their temples with dead men’s records, as relics, and waste their youth in solitude and tears.” – Hermes Trismegistos. [21]

- Long term storage.

The definition of the term Archival Storage In An Oasis is derived from the tale of Gilgamesh, who was buried beneath a record store in Leicester, which had been temporarily diverted by the local citizens.

- Deterioration.

Deterioration of magnetic media can be ensured by the inappropriate use of sunlight, dust and cardboard.

- Disorder.

“Dirt is disorder, matter out of place.” [22]

- Test tones and notariqon.

“Amaranth sasesusos Oronoco initiation secedes Uruguay Philadelphia” [23] is the aligners’ secret seven-word sentence for testing typewriters, a nonsensical yet appealing phrase with a deeper equivalence in alchemy. Vitriol is a seven-word alchemical cipher using a system known as notariqon, wherein letters spell out instructions. In the case of VITRIOL, the inner function of the philosophic solvent (sulphuric acid) equates to Visita Interiora Terrae Rectificando Inventes Occultum Lapidem, literally, “visit the interior of the earth and by rectifying you will find the hidden Stone.” [24] Shadows of pre-Renaissance notariqon persist in sound recording terminology, albeit as terser and more prosaic ciphers for financial and intellectual property belonging to international corporations and standards committees, and those best placed to resupply you on their behalf – LP (Long Playing Microgroove), RCA (Recording Corporation of America), DIN (Deutsches Institut für Normung), ADAT (Alesis Digital Audio Tape), S/PDIF (Sony/Philips Digital Interface Format), and TOSLINK (Toshiba Link). - Meaning.

Elliot W. Eisner (1933-2014): “The limits of our cognition are not defined by the limits of our language… Meaning is not limited to what is assertable.” [25]

Postscript: A Note on Temporal Drag? The Analog and the Digital.

The past is still with us. We impose no restriction or definition on the collection of objects past/present, tangible/intangible, analog/digital, physical/virtual, but we resist the temptation to lock objects into artefact status. Objects will be destroyed if they risk analog deification. Digital ubiquity is a false god.

Notes and References

[1] Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland (London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., first edition 1898, reprinted 1908), 105.

[2] Ryan Griffis, anti-archive; Rosalind new media art lexicon, 2004, http://furtherfield.org/lexicon/anti-archive (accessed 14 Feb 2016)

[3] H. Jennings & C. Madge, with T.O Beachcroft, J. Blackburn, W. Empson, S. Legg, & K. Raine, May the Twelfth: Mass Observation Day Surveys (London: Faber & Faber, 1937), 228-9.

[4] Jennifer Wicke, “Vampiric Typewriting: Dracula and Its Media,” English Literary History Vol. 59, No. 2 (summer 1992): 467-93.

[5] Bram Stoker, Dracula (London: Archibald Constable and Company, 1897).

[6] Can, “Hunters and Collectors,” Landed. Virgin V2041 (UK),1975, LP.

[7] Jennifer Wicke, English Literary History Vol. 59, No. 2 (summer 1992): 492.

[8] Fernando Gozzini, Peter Kubelka, Eugenio Medagliani, Pastario or Atlas of Italian Pastas (Lodi: Biblioteca Culinaria, 1985).

[9] “Whatever is an archivist?”, Yorkshire Evening Post, June 1, 1937; page 13, column 6.

[10] Blade Runner, dir. Ridley Scott, screenplay by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples, adapted from the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick (1968). Michael Deeley (1982).

[11] Nathan Anisko and Eric Anderson, “Average Length of Top 100 Songs on iTunes, Dec. 2012,” StatCrunch, http://www.statcrunch.com/5.0/viewreport.php?reportid=28647&groupid=948 (accessed March 20, 2016).

[12] Jorge Luis Borges, Labyrinths: selected stories and other writings (London: Penguin Modern Classics, 1987), 279.

[13] Cal Schenkel, cover artwork: Frank Zappa & The Mothers of Invention, One Size Fits All. DiscReet K5920 (UK), 1975, LP. “Chewy Caramel Center” appears on a map of the solar system, top right of the LP front cover, with an arrow pointing at the sun.

[14] Kevin Bradley, ed., Guidelines on the Production and Preservation of Digital Audio Objects: Second Edition (South Africa: International Association of Audio Visual Archives, 2009), 28.

[15] Tape Recording and Hi Fi Magazine Vol. 2 No. 9 (Sept. 1958): 58.

[16] Jorge Luis Borges, Labyrinths: selected stories and other writings, 78-86.

[17] Ben Watson, Frank Zappa: The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play (London: Quartet Books Ltd., 1994), 103.

[18] Frank Zappa, Lumpy Gravy. Verve SVLP 9223 (UK), 1968, LP.

[19] Ben Watson, Frank Zappa: The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play (London: Quartet Books Ltd., 1994).

[20] Frank Zappa & The Mothers of Invention, One Size Fits All. DiscReet K5920 (UK), 1975, LP.

[21] J. J. Champollion-Figerac, Eqypte ancienne (Paris, unknown 1847), 27.

[22] Bill Laswell, “Káshí,” composed by Tetsu Inoue, City of Light (1997). Sub Rosa 2009, AAC audio file.

[23] Darren Wershler-Henry, The Iron Whim: A Fragmented History of Typewriting (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2007), 137.

[24] Kenneth Rayner Johnson, The Fulcanelli Phenomenon (Jersey: Neville Spearman Ltf., 1980), 316.

[25] Elliot Eisner, ‘What can education learn from the arts about the practice of education?’, The Encyclopedia of Informal Education; 2002/2005.

http://www.infed.org/biblio/eisner_arts_and_the_practice_of_education.htm (accessed 22 March 2014).